Last summer a statue of the suffragette Emily Wilding Davison was unveiled in Epsom, near the racecourse where she was trampled to death by a horse while attempting to draw attention to the cause of Votes for Women.

Hers is not the only statue to have been unveiled in recent years.

In 2018, to mark the centenary of some women achieving the Parliamentary vote, Glasgow unveiled a statue of political activist Mary Barbour.

In the same year, Manchester unveiled statues of suffragette leaders Emmeline Pankhurst and Annie Kenney and, in 2019, of woman footballer Lily Parr.

The Public Statues and Sculpture Association lists 112 public statues of non-royal females in the UK in its useful database.

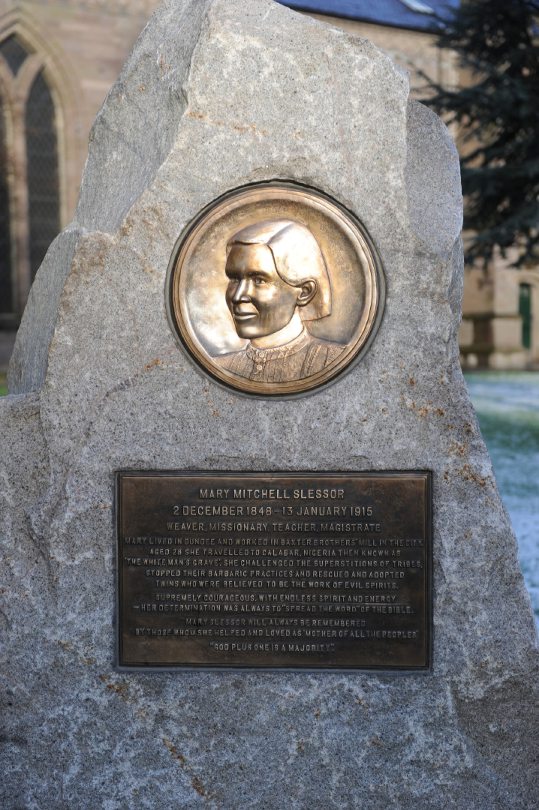

Searching it with the word “Aberdeen” brings up only one entry – Mary Slessor, who was born in Aberdeen but moved to Dundee as a child.

One statue honouring Mary can be found in Nethergate, Dundee.

There is, of course, also an apple-shaped granite monument in her memory in Union Terrace Gardens which will be going back when its revamp concludes.

The Women of Scotland website also offers a database to search.

It lists more than 900 memorials celebrating women throughout Scotland.

The database does list a number of plaques and other memorials to women around Aberdeen, but only two statues. They are both of Queen Victoria.

Walking around Aberdeen, you can pass statues of William Wallace, Edward VII, Robert Burns, General Gordon, Prince Albert and Robert the Bruce.

And, of course, the new statues of Denis Law and Alex Ferguson have added to this number.

Does it matter that Aberdeen seems to want to place only men (and Her Majesty) on a pedestal?

Statues are controversial these days, with continuing debate over the final placement of the statues of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol or British imperialist Cecil Rhodes at Oriel College, Oxford.

Why do statues matter to Aberdeen?

Do we need new statues of women in Aberdeen?

Or are they an anachronistic relic of the past that society is rightly beginning to reject?

The memorials we put up in public spaces reflect a society’s values and the issues and people that they find important.

Statues can also inspire and educate, allowing us to start discussions about the people portrayed and their achievements.

Does the limited number of statues of women in Aberdeen reflect civic attitudes to the value of women in the city’s history? Surely not.

Celebrating women working together

Aberdeen does have memorials to women – my favourite being the mural by Carrie Reichardt from the 2018 NuArt festival.

Titled Deeds not Words, it features a number of women who campaigned for women’s rights in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It features geologist and politician Dame May Ogilvie Gordon, naturalist and women’s rights activist Marian Farquharson, Ishbel Lady Aberdeen and the female education pioneer Louisa Innes Lumsden, all surrounding an image of Aberdeen’s own suffragette, Caroline Phillips.

I have to confess that I prefer this collective approach to celebrating the achievements of women.

This method perhaps more accurately reflects the way in which women have achieved change – by working together.

Land Army monument an example

For that reason, I also prefer the collective memorials to women that have appeared in recent years.

This includes Dundee’s Jute Women, Stornoway’s Herring Girls, and the striking memorial to the Women’s Land Army at Clochan.

These collective memorials also reject the ‘Great Man’ view of history, which suggests that historic achievements were the result of one man’s endeavours and leadership.

The statue of Millicent Garret Fawcett, leader of the Women Suffragists, again unveiled in 2018, includes the names and images of 55 women and four men who supported women’s suffrage on its plinth.

It acknowledges that the achievement of the women’s vote was the result of a collective effort.

I also like the fact that several of the new memorials to women depict them sitting on a bench, with room for the viewer to sit beside them.

They are not positioned above the viewer but as part of the community, encouraging other women to join them and perhaps consider their own contributions to public life.

Statues should celebrate but also inspire. What sort of inspiration does a young girl see when she walks around Aberdeen?

- Sarah Pedersen is Professor of Communication and Media at Robert Gordon University.