The heroic actions of a soldier who survived the horrors of Dunkirk, but was killed trying to save a child at a beach near Peterhead, have been immortalised in a new archive.

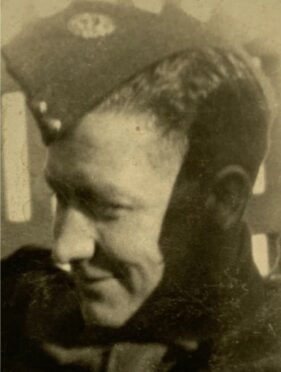

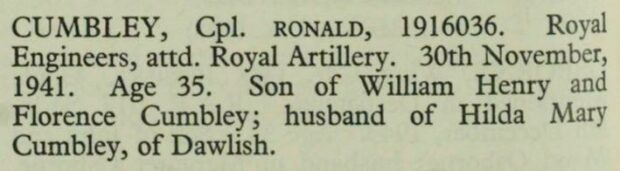

Corporal Ronald Cumbley was among the brave troops who answered Churchill’s call to “fight on the beaches” at Dunkirk in 1940.

A soldier with the 661st General Construction Company of Royal Engineers, he was posted to France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to hold off Nazi invasion.

But the BEF was taken by surprise when Hitler unleashed a sudden, co-ordinated Blitzkrieg attack by land, air and sea.

Allied forces were pushed back to the French port of Dunkirk, and Ronald was among the 338,000 men penned in by the Nazis.

The only option was a risky one: to evacuate hundreds of thousands of troops from the beaches, across the English Channel and back to Britain.

Ronald lived to tell the tale as one of the men rescued by a hastily assembled fleet of more than 800 vessels ranging from Royal Navy Destroyers to civilian yachts.

Although it was a retreat and 68,000 lives were lost, the Dunkirk evacuation was still considered “a victory snatched from the jaws of defeat”.

Back in Britain

Born in Wales, Ronald was a master painter and decorator who lived in Devon with his wife Hilda and 10-year-old daughter Anne, before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Upon returning to Blighty, Ronald was posted to the 942nd Defence Battery in Aberdeenshire, which controlled coastal defences from Forvie up to Peterhead.

The anti-aircraft batteries and naval guns were crucial in fending off potential German invasion and protecting the aerodrome at Longside.

A world away from the frenzy and fear of Dunkirk, Peterhead would have seemed like a peaceful posting for the 35-year-old soldier.

The surrounding beaches formed part of the Rattray stop line, comprising of anti-tank ditches and defences.

St Fergus Links and Craigewan Sands near Inverugie were laid with landmines amid fears it could be used as a landing area by the enemy.

Peril at Peterhead

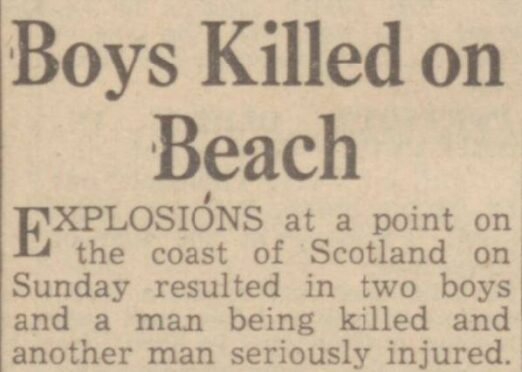

But the horror of war was brought home to Peterhead on St Andrew’s Day in 1941, not by the Nazis, but the curiosity of children.

It was perhaps Ronald’s fatherly instinct, rather than his military training that kicked in when he spotted four schoolboys entering a prohibited area of Craigewan Beach on that November afternoon.

Mortal danger lay ahead, and moments later 11-year-old John Paul and 12-year-old James Reekie had triggered a landmine.

One of the boys was killed in the explosion and the other was left screaming in pain, John Paul’s two young cousins were left unscathed.

Ronald couldn’t bear to hear the child suffering. Along with local shepherd Donald Forsyth, and fully aware of the risk he was taking, Ronald went to the boy’s aid in the hope he could save him.

But he never made it.

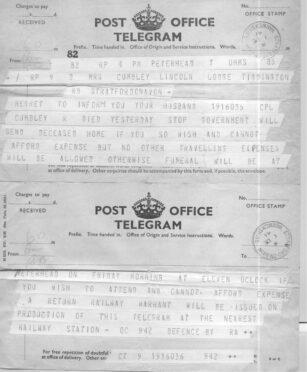

It was an act of sheer bravery that cost Ronald his life, just a week before he was due to return home on leave.

He activated a second explosion and was killed instantly, shepherd Donald was seriously injured.

It was a tragedy that robbed a little girl of her father, and for John Paul’s family, it robbed them of their only child.

Ronald’s final act of heroism was recognised by his commanding officer who wrote to his mother Florence in Devon paying tribute to his gallantry.

Never forgotten

Now, 80 years on, Ronald’s grandson Andrew Castle is keen to keep his grandfather’s memory and heroism alive.

Andrew said: “As an ex-soldier myself, I often reflect on the fact that he survived Dunkirk and, in what must have seemed like a period of respite in Scotland, was faced, on a grey and unremarkable day, with the hardest of decisions.

“And he stepped up. Of course, the effect on his family, and my mother Anne, was devastating.”

Ronald was buried back home in Kingsteignton, Devon, where his name features on the parish war memorial.

But now Ronald’s story also features online as part of an interactive memorial wall to ensure tales like his are not forgotten.

The Armed Forces Memorial Wall is an initiative from the Veterans’ Foundation preserve the memories of the men and women who dedicated their lives to serving their country.

Andrew added: “I always felt a little sad that my grandfather’s actions went mostly unnoticed, another tragic incident in a long war.

“I am a British consular officer, so occasionally find myself assisting ex-servicemen and their families, which I find to be a supremely rewarding part of the job.”

Part of the work carried out by the Veterans’ Foundation is to help veterans in need today, and the memorial wall is a way for people to donate to these life-changing projects.

If you enjoyed this, you might like: