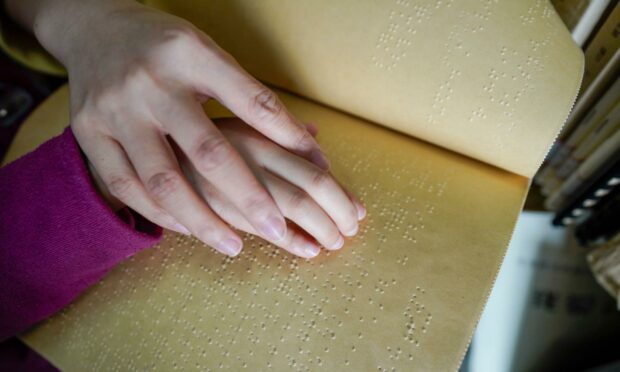

For Aberdeen pensioner Richard Foster, using braille is “as natural as breathing”.

He is one of countless blind people to have had their lives enhanced by the tactile code, which enables him to read and write by touch.

But its creator went to his grave with no idea about the impact his “wonderful” invention would have on the lives of millions across the world.

Now, Mr Foster is helping to celebrate the code’s father, Louis Braille, on the anniversary of his birthday in 1809.

Braille still ‘as vital as ever’

Mr Foster learned braille when he attended a school for blind children in 1956.

More than 65 years later, he is using it in his everyday life as the main tool to run his successful business, get information, learn music and read for pleasure.

“I use braille every day for reading and writing text and, when I need to, for learning piano music,” he said. “Not surprisingly, after continually using braille for 65 years, I find it very easy to use. For me, it’s as natural as breathing.

“For a blind person, the advantage braille offers when compared with audio is it develops the ability to get a real handle on the way language works. Good spelling is learned automatically.

“It also means you do not rely on somebody’s interpretation of the text. Your imagination is stimulated to create voices of characters in works of fiction.

“I also find from personal experience, when learning things, they stay in the memory much when reading rather than merely listening.

“Modern technology means braille can be produced easily and cheaply. It’s a wonderful invention. Such a pity its inventor had no idea how universally it would be adopted when he died.”

Modern technology merges with centuries-old system

There are braille codes for the vast majority of languages, with various combinations of raised dots representing the alphabet, words, punctuation and numbers.

The system is based on variations of six dots, arranged in two columns of three, with a total of 63 combinations.

Beginners mainly start with braille that represents each letter as one “cell”, but more experienced users read and write a shorthand form where groups of letters are combined into a single cell.

Although some presumed modern technology will make the system “obsolete”, it has made braille even more accessible to those who need it to lead a normal life.

James Adams, director of the country’s leading sight loss charity RNIB Scotland, said: “The invention of braille is often compared to the invention of the printing press for sighted people. For thousands across the world, braille means independence, knowledge and freedom.

“Modern braille-writing equipment can connect seamlessly with personal computers and mobile devices like tablets and smartphones, while text-reading software can vocalise back to you what you’ve inputted. Dots, letters, numbers – it’s all just input information to a computer.”