“Bones are my thing,” Ali Cameron confides with a grin.

The archaeologist is referring to the ancient kind, rather than any skeletons in her closet.

Ali, who worked for the council for decades before starting her own business, has uncovered scores of crypts while excavating storied sites all over the north-east.

She was recently called upon to help out while drains were being repaired during a £1.8 million upgrade of St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen.

During the project, a pit of medieval bones was unearthed – a ragtag assortment of disembodied skulls, arms and legs.

But Ali says that the fascinating find offers just a tiny glimpse into the hidden past of the building.

Ali believes there could be as many as 2,000 skeletons lurking beneath the floor of the Old Aberdeen landmark.

‘There were femurs and tibias and skulls’

Giving an eye-opening talk on the find, the owner of Cameron Archaeology told a crowd at the cathedral her “ideal place is in a trench”.

She was a regular visitor to St Machar’s while repairs were being carried out between 2019 and 2021.

Workers made sure to dig trenches no wider than necessary to avoid disturbing any burial sites as they replaced damaged drains.

But one day they struck something unusual.

Ali quickly confirmed it was a medieval bone pit, with two layers.

She added: “I carefully excavated the pit to allow them to put the drain in.

“I laid the bones all out to see what we had, there were femurs and tibias and skulls. But there were no whole skeletons at all.

“Though we were all fascinated, that means we are limited in what we can learn from them.”

After the examination, and when the new drain was installed, she returned the bones to their resting place…

Ali Cameron on mystery of remains beneath cathedral

However Ali is familiar with similar sites in Aberdeen – she helped dig up 1,000 bodies from the city’s St Nicholas Kirk more than a decade ago.

And suspects the jumbled bones are a small fraction of what lies under the building itself.

The cathedral site dates back to between 540 and 600 AD, and there was major rebuilding in the 15th century.

It has never been excavated in modern times.

St Machar’s is a scheduled monument, which means any work is prohibited. Therefore, its secrets could be destined to remain hidden.

“We don’t disturb anything we don’t have to,” Ali explains.

But, using her years of expertise, she is able to predict with some confidence just what might be down there.

Ali said: “Based on other sites in Aberdeen, I can tell what St Machar’s would be like.

“We know people wanted to be buried under the floor of the church, particularly to the east of the building.

“So going by the size of the cathedral, there could be as many as 2,000 skeletons down there.”

The fascinating insights skeletons can offer into life in Aberdeen centuries ago

Ali tells us we can learn a lot about a society from the remains left behind.

One insight gleaned from the graves found at St Nicholas in 2006 was the medieval tendency to adorn some burial sites with mussel shells.

Ali said: “The mussels were all opened and placed face down over the graves of children.”

Though the exact reason is lost to the sands of time, there has long been an association with shells and religion.

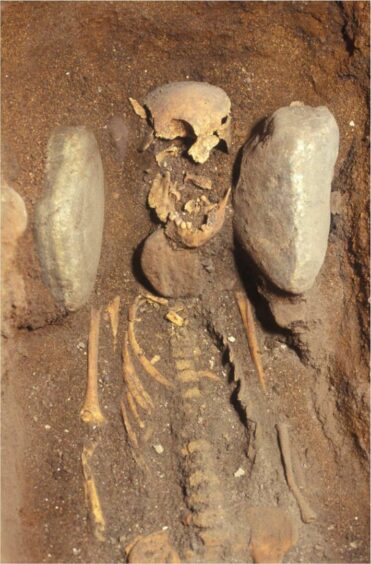

Another discovery at the Mither Kirk was the presence of “cheek stones” to keep the heads of deceased loved ones in place.

As well as some by the side of the skull, stones would also be placed under the chin to make sure people retained a dignified pose, with their mouths shut, in death.

Ali also believes a body found in St Nicholas with its legs crossed may have been buried that way to signify that the man took part in the 13th century Crusades.

Others, meanwhile, bore the marks of battle – with archaeologists able to pinpoint the cause of death even several centuries on.

While St Machar’s is unlikely to reveal its secrets any time soon, Ali’s work means Aberdonians can enjoy a vivid picture of what the city was like many centuries ago.