He was born in a house in Stonehaven which was known as “Beefy Castle” because it used to be the home of a prominent butcher.

And even though John Reith soon left with his parents for Glasgow, the man who became the founding father and first director-general of the BBC 100 years ago never forgot his links to the north-east coastal community.

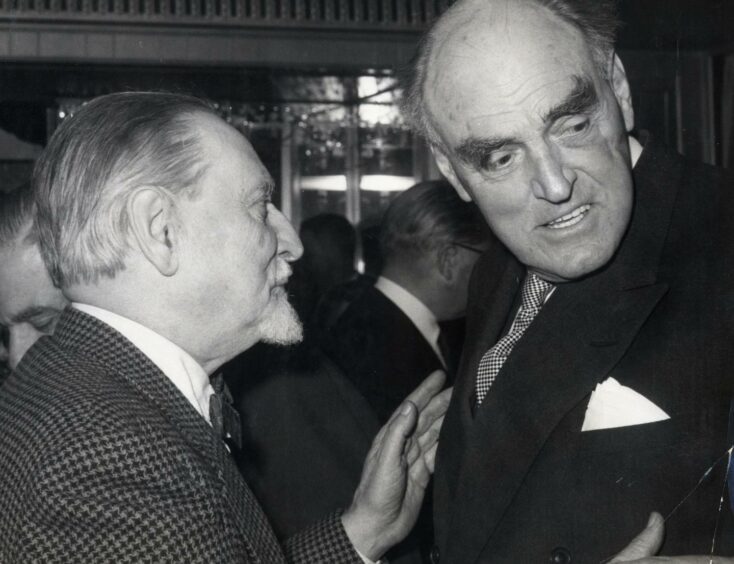

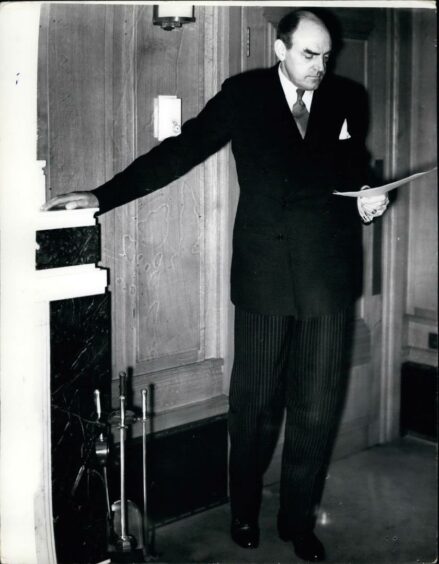

A titan of broadcasting, even if he didn’t know what the word meant when he went for an interview with Sir William Noble – from Aberdeen – in 1922, Reith was a giant at 6ft 6in, whose autocratic decisions often made him a formidable and fearsome opponent for those who dared to question him.

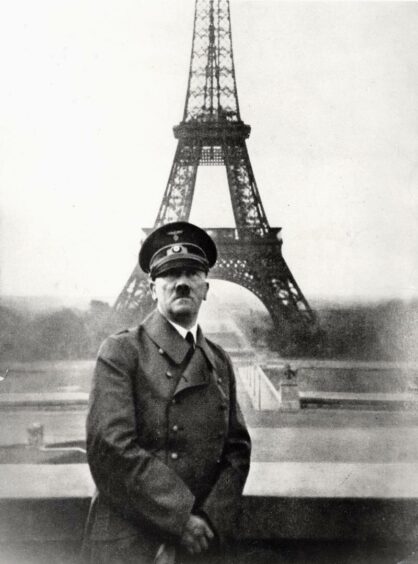

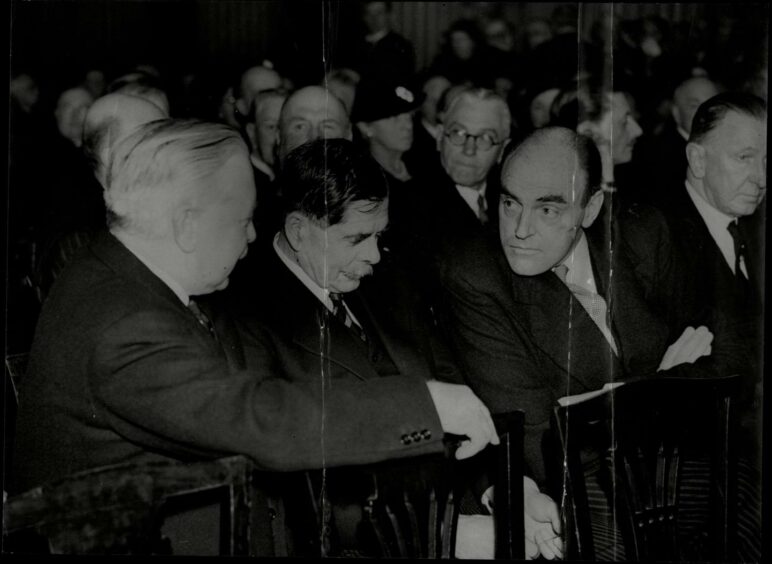

And, while there is no doubting how he helped change the world in the 1920s and 1930s by introducing millions to the power of radio and creating the template for the corporation, he was a deeply flawed individual who admired Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, loathed Winston Churchill, and believed that the creation of commercial channel ITV was akin to an act of desecration.

Indeed, his opinions were so controversial that despite adopting the title Baron Reith of Stonehaven, the local council twice voted against a “modest plaque” being erected at his old home in Evan Street in 1970 and 1972.

But were they right to be wary?

Let’s take a look at some of the good, the bad and the ugly aspects of the Scot whose affirmed mission was to “inform, educate and entertain”.

He nearly didn’t survive the war

Reith was never comfortable taking orders from authority figures, even as he displayed his courage during the First World War.

In September 1915, the 26-year-old lieutenant, who had served an engineering apprenticeship in London, joined the Highland Field Company Royal Engineers and arrived at the Western Front during the offensive at Loos.

He later wrote in his autobiography Wearing Spurs: “I had never witnessed such sights before; this was indeed a dreadful battlefield. I had seen dead men and dead horses, but never in these numbers.”

Soon enough, he almost joined them. Just a month later, he was sent to repair a section of a trench which had been destroyed by a mine.

But, while carrying out the work, he was shot in the head by a German sniper. Some of the bone in his face was blown away – and it was a conspicuous feature for the rest of his life – and he lost a lot of blood in the process.

But he survived and resolved to seek a vocation which would test his mettle after the hostilities.

His initial Eureka moment came when he spotted an advertisement while he was scanning the situations vacant section of The Times in October 1922.

This read: “The British Broadcasting Company (in formation). Applications are invited for the following officers: General Manager, Director of Programmes, Chief Engineer, Secretary. Only applicants having first-class qualifications need apply to Sir William Noble, Chairman of the Broadcasting Committee, Magnet House, Kingsway, WC2.”

Reith was intrigued and excited and actually popped his initial application into his club’s post box before he read about Noble – a former lecturer in electricity and telegraphy at Robert Gordon’s College – in Who’s Who and discovered he had strong Aberdeen connections. At which point, he persuaded a colleague to remove the letter from the box, so he could rework it with a few significant mentions of his own north-east Scottish ancestry.

The ploy worked and the pair met in what might have been a catastrophic interview, given that he confessed: “I did not know what broadcasting was.”

However, that didn’t harm his chances. And, in the space of a few weeks, Reith was appointed as general manager, blissfully ignorant of his role, but determined, as he subsequently wrote: “To bring every casual conversation round to ‘broadcasting’ until one of my acquaintances enlightened me.”

By the end of the year, he had an office, little bigger than a store cupboard, but as a deeply religious figure, remained convinced he was destined for a higher calling. He was right about that. And he also developed the reputation as being somebody who didn’t suffer fools at all, gladly or not.

One colleague memorably recalled: “He would look through you like a dowager duchess meeting a chimney sweep in her boudoir.”

But, within five years, and despite crossing swords with the Conservative Government during the General Strike in 1926, he had become the inaugural director-general of the BBC, an organisation which was funded by a licence fee at a rate fixed by parliament and paid by all owners of radio sets.

It was as globally unique as the National Health Service would later become. Yet, if he had grand aspirations – “The whole [BBC] service may be taken as the expression of a new and better relationship between man and woman and carry the best of everything into the greatest number of homes” – Reith often found himself in conflict with politicians and the state.

The DG demanded his staff wore DJs

He always insisted that he had a mission to educate and enhance the lives of his audience and, under his stewardship, the corporation developed a global reputation for creating serious programmes.

A stickler for observing the formalities, the D-G decreed that all radio announcers should wear dinner jackets while they were on the air, even though nobody outside the studio could see them. When interviewing potential employees, he would commence the interrogation by asking them: “Do you accept the fundamental teachings of Jesus Christ?”

As the 1930s progressed, he recruited several talented female producers, including Grace Wyndham Goldie from Arisaig in the Highlands, whose impact as Head of Current Affairs was profound and left a positive impression on a young David Attenborough – “She was one of the most influential of all television’s pioneers” – when he joined the BBC in the 1950s.

But, regardless of his drive towards encouraging youngsters to broaden their minds and for nation to speak unto nation, Reith’s bold vision was increasingly distorted by his backing for fascists as the 1930s advanced.

He wasn’t alone in this, of course, given the Daily Mail’s support for Oswald Mosley and his “Blackshirts” in the early part of the decade, but the head of the BBC did reach some extraordinary conclusions – and wrote them down.

Thus, in March 1933, he said: “I am certain that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again….they are being ruthless and most determined”. Then as late as 1938, when Prague was occupied, he responded: “Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency.”

He was similarly enthusiastic about Mussolini in 1935 when he noted in his diary: “I had always admired him immensely and constantly hailed him as the outstanding example of accomplishing high democratic purpose by means which, though not democratic, were the only possible ones.”

It was a different matter altogether when it came to his relationship with Churchill which started badly during the General Strike when Reith was determined to ensure the fledgling BBC remained politically neutral.

The then Chancellor of the Exchequer explained: “I first quarrelled with Reith in 1926, during the General Strike. He behaved quite impartially between the strikers and the nation. I said he had no right to be impartial between the fire and the fire brigade. The nation was being held up.”

Later, when Churchill made some broadcasts about India in 1935, they were scathingly described by Reith as: “Awfully disappointing – a string of bombastic phrases with little sincerity at the back of it.”

It was a clash of volcanic wills and contrasting temperaments and the situation grew worse when Churchill dismissed Reith from a government role as Minister of Works and Buildings during the Second World War, claiming he was “impossible to work with”, before fobbing him off with a baronetcy.

In the aftermath of the conflict, the Scot, who had previously departed the BBC and become chairman of Imperial Airways in 1938, repeatedly referred to Churchill as “an impostor”, a “menace” or “that s**t” and went so far as to say: “It will be a hundred years before Britain ever gets over the malign influence of that unscrupulous man”.

By this stage, he had become disillusioned with the influence of television on society and was apoplectic at the launch of a commercial rival.

He said in the House of Lords in 1954: “Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting….need we be ashamed of moral values, or of intellectual and ethical objectives? It is these that are here and now at stake.”

To put it kindly, he was past his sell-by date.

Stonehaven wasn’t keen to honour him

Given his role in one of the major developments of the 20th century, one might have imagined Reith would be regarded with affection in Stonehaven.

But the underwhelming response of the council to a motion put forward by Cllr Alice Blacklaws in 1972 – the year after Reith’s death – told its own story.

The Press & Journal reported: “Her motion, calling on the authority to honour Lord Reith’s memory by placing a ‘modest’ plaque at the house where he was born in 1889 was defeated by seven votes to two.

“And there was swift opposition from Cllr Mary Taylor who said: ‘I have spoken to a number of people in the town who feel it is not proper. The man has done nothing for the town. Most people here don’t even know who he is’.”

There is a little tribute in Stonehaven nowadays to one of broadcasting’s pioneering figures, but it’s not something the town really boasts about.

A sorry epitaph for a man who spearheaded a revolution!

You might also like:

Andy Stewart: How the Red Lichtie was the king of Hogmanay TV

Sunset Song: Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s portrait of man and Aberdeenshire is 90