Rail accident investigators don’t just exist to establish why accidents occurred, but also to ensure they don’t happen again.

Within the 300-page report into the Carmont derailment, 20 recommendations have been made to avoid a similar crash in future – not just at Stonehaven but all across the rail network.

Each of the recommendations is addressed to the UK’s safety authority, the Office of Rail and Road, but in reality Network Rail will be the body undertaking most of the action.

Network Rail is now required to consider the recommendations and report back to the Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) on the action it is taking, or the reasons why no measures are being implemented.

What are the recommendations?

The 20 recommendations cover three main areas of the investigation:

- The reason the drain flooded

- The difficulties faced by rail staff on the day

- Safety concerns regarding the train’s crashworthiness

At first glance, the recommendations themselves can seem quite simple or vague.

For example, recommendation number one relates to the finding that the flooded drain was not installed as it had been originally designed.

It is recommended that Network Rail “review its contractual and project management arrangements” as a result.

This essentially means the RAIB want to see robust quality control requirements put in place including things like checks during construction and penalties for not complying with the required processes.

Other key recommendations relating to the failed drain include ensuring new works are definitely included on regular inspection lists (this drain was missed for many years) and improving drainage designs to ensure future drains aren’t susceptible to this issue.

Recommendations relating to rail staff

There are seven recommendations which relate directly to rail management, meaning that the RAIB obviously think there is room for a lot of improvement.

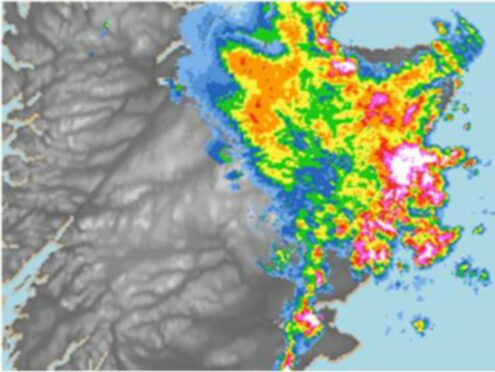

The overarching theme is that railways need to get better at responding to both predicted and actual extreme weather events, particularly extreme rainfall.

RAIB recommends that Network Rail improve its processes for “mitigating rainfall-related threats” in various different ways, including by identifying any potential hazards to the network, not just ones it considers to be especially high-risk.

This caught operators out at Carmont as the earthworks and drainage there was not on Network Rail’s high-risk list.

Other recommendations relating to staff include increased training on any new weather mapping technology and training control room staff how to react to highly stressful or “unusual situations such as abnormal weather conditions and multiple infrastructure failures.”

Recommendations regarding the train itself

The third main area which accident investigators deemed a need for significant improvement was on the train itself.

The train was made up of four Mark 3 passenger carriages with a power car at either end.

This type of carriage was built between 1975 and the early 1990s meaning that many of the Mark 3 carriages on British railways are in excess of 40 years old.

It might seem odd that ScotRail are using carriages which are nearly half a century old, but in the world of railways this sort of thing is common practice and considered safe.

The routes which are the busiest and cover the most ground, such as trains coming in and out of London, get the newest trains, and when these trains are replaced, the old models are given to an operator with a less demanding route.

This does mean however that these trains fall outside modern crashworthy standards, which apply to trains built after 1994.

Recommendations made by RAIB include reviewing everything from how train windows shatter on impact, how folding tables may cause injuries and if train drivers should have the protection of seatbelts and airbags.

The recommendations also reiterate the importance of keeping the carriages securely together and inline to avoid the coaches jack-knifing or splitting off entirely as happened at Carmont.