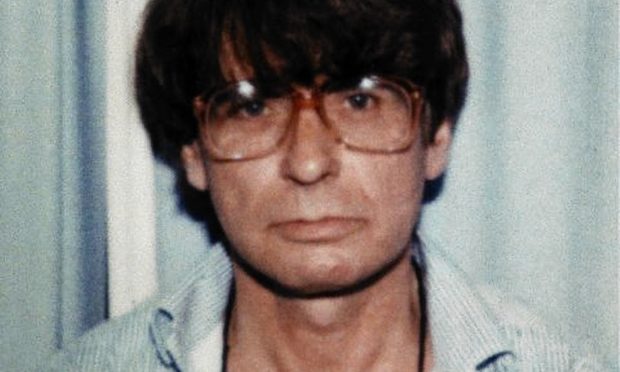

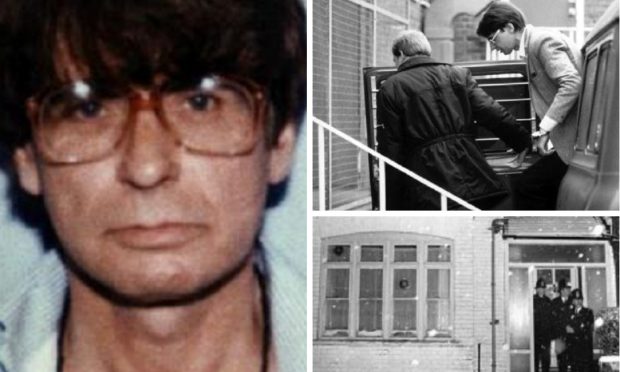

Dennis Nilsen spent many of his childhood years in Fraserburgh and Strichen – and went on, years later in London, to become one of the world’s most infamous serial killers.

Between 1978 and 1983, he murdered 15 men in the capital after meeting his often homeless victims in pubs.

Nilsen lured them to his homes at Cricklewood and Muswell Hill in London, killed them and then carried out bizarre rituals.

His killing spree was eventually brought to an end and he was sentenced to life imprisonment at maximum security HMP Full Sutton in Yorkshire.

More than 30 years later, his actions are still impacting on the lives of his victims’ families – most recently with his fight to publish his autobiography, which has been described as glorying his crimes.

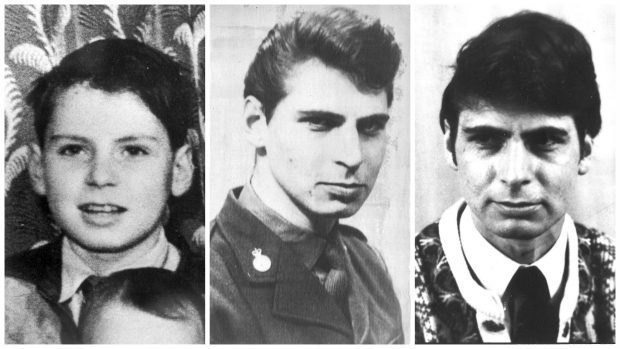

Writer and artist Shane Levene, 38, son of Motherwell-born Graham Allen, who was killed by Nilsen in 1982, would be within his rights to follow suit in attempting to stop the book from hitting the shelves.

Now living in Lyon, France, Shane tells us about how his experiences have given him a surprisingly objective perspective on the life and times of the notorious killer.

Where did you live before your father was killed? Fulham, London

How old were you? Seven

What do you remember about his death? My mother screaming after being told. She says that wasn’t her first reaction, but that’s what I remember. I regard that as my birth; the moment I came into existence. Regarding the actual news of his death, it didn’t really have any effect on me.

At that moment, he was only rumoured to be my father, and I waved those rumours away, desperate to share the same father as my brother and sister. I didn’t want to be only half-something to them. And also, it wasn’t like my father was always at home and then one day was not. Due to his drug addiction, he was living in a separate place to my mother, and by the time we learned of his murder, he had already been missing for over a year.

How did you feel when it was discovered he was killed by Dennis Nilsen?

Honestly, more than anything, at that age, I kind of felt special that my father was one of the victims, that our family was somehow mixed up in the hideous events which were front-page news the entire length and breadth of the nation.

I couldn’t wait to tell people, to kind of distinguish myself. Of course, no one believed me and so eventually I stopped talking about that at all. But all my life I suppose I kind of enjoyed that fact. I mean, if your father is going to be murdered, who better to murder him than Britain’s most evil killer? That sounds strange, I know, and it’d be easy to lie and give you the kind of standard responses that everyone expects, but that’s not how I felt. At that age, seven, when you’re bustling and fighting to stand out, such things are used in a very different way than they would be if happening to you as an adult.

How do you feel about it now?

It’s a part of my life and history and I celebrate all that has gone into the making of me (good and bad). The murder is one of the defining events (but not the defining event) which formed me. Such events take on a kind of neutrality after three decades of living with them. Like other events, it’s just something which happened and which can’t be changed and, though it was a hideous thing, it doesn’t mean it has to have hideous repercussions. So I see it in a very forming and essential light: it is a part of the history to who I am today and I can’t and wouldn’t want it to be any other way.

Has his murder affected your life in any way?

Of course the event has affected my life, but not so much in an emotional way, more in a physical sense, in how it has often been the road on which I have met great people and had more exposure as a writer. The emotional effects, and there were many, did not arise from the murder itself but from the consequences the murder had on my mother – she became a chronic and suicidal alcoholic.

Her reaction to the event, her coping mechanism, was where emotional hurt entered my life. And that there is the defining event of my life: my mother’s reaction to the murder of the only great love of her life. So I class myself as a secondary victim of the murder, whereby the event didn’t affect me but what that event did to my mother, and her consequent behaviour, did. And although childhood from that point on was horrendous and my youth corrupted, I have no bitterness or regret over that. I saw a world and was dragged into an underclass of living that very few will ever see. It was horrendous and vulgar and perverted, but gave me unique eyes and a unique insight into suffering and despair: a masters degree in the filth of life.

How do you feel about Dennis Nilsen trying to publish his autobiography?

As a writer, I naturally understand that and find it quite sane. Who wouldn’t want their life text published? It would be weirder to me (and a sure sign of insanity) to write a 6,000-page autobiography and not want it published. As a victim, if that’s what I am, I would also like to see his writing published and would love to read his words, uncensored and honest – honest in the sense that those words were not written with parole in mind.

It seems strange to me that when he writes from the heart and is openly blunt and forthcoming about his crimes that people want to suppress his words. But, when he says stuff which he obviously doesn’t feel, for ulterior motives, then his words are all splashed around. So if his words are in every paper across the UK, well, isn’t that also him being published? There’s a whole lot of hypocrisy and nonsense logic around this question. It’s like the powers-that-be don’t want to know his real feelings, they want to take away all the words which they don’t want to hear and leave only those which give the impression that the criminal justice system and rehabilitation works. It’s like Orwell’s Newspeak from his novel 1984 where the only words left are what the government want us to say, and we can say no more.

How do you feel about people reading intimate details about your father’s death?

Oh, people were reading intimate details of my father’s life when he was living, so what’s the difference? In fact, after my birth, my father disappeared out my mother’s life for a year and she only got back in contact with him when his name and address cropped up in the local paper after he’d been up in court accused of stealing a clock from the doctor’s surgery. So it doesn’t bother me. And, as I’ve probably released more intimate details of his life than anyone else, I can only say that.

How do you feel about the fact Nilsen’s autobiography has been described as glorifying his crimes?

By who? The press? No one but Nilsen’s lawyer and one or two close confidantes have read it (it’s not published, don’t forget) so who can say whether it “glorifies his crimes” or not? And even if it does, and that’s honestly how he feels towards his actions, isn’t that extremely interesting? Shouldn’t the public and psychiatrists and forensic psychologists and criminal profilers be grateful for such a first-hand account and unashamed glorying of such a crime? To me, such a book would be extremely useful and insightful to many people. So whether it glorifies the crimes or tries to explain them, I think the book has every right to be published, and I think it’s in the public interest to do so. For the argument that “it’s not in the victims’ interest to do so” well, I don’t believe that’s true, but even if it were, I don’t think a handful of bitter people (bitter for very good reason) should decide the fate of the nation. If the book’s published, the victims have every right not to read it and the public has every right to boycott it, but it must be available. As my mother recently said, “Why should he have his book published?” Though yeah, if it were published I’d probably read it.

Nilsen was recently quoted as saying: “In the relative twinkling of an eye, I will have to face my own death just like any other victim. I deserve to experience the same degree of pain suffered by my victims. Nothing less will suffice. “Only my own death will eventually even the score and only at that point will I know that I am forgiven and am finally free of that burden of debt. In the intervening period in what remains of my life, I will try to be worthy of it.”

How do you feel about what he is saying?

Dennis is old now and the death process has truly set to work on him. He doesn’t have long left and, like anyone, I suppose, he wants his freedom. He knows he’ll never be released but he’s human and he hopes against hope. Those words above came from Nilsen but are not from his heart. They are the words that society and justice force him to say if he’s to have any chance of being released. It’s clearly stated: You will not even be considered for parole without feeling remorse. Not whether you’ve served your time or are no longer a danger, etc. but you must feel remorse. So criminals have their arms twisted up behind their backs to be and act remorseful. And, if by pretending to be remorseful halves your prison time or leads to freedom, then of course they’ll say or act it. I’d do the same.

Truthfully, who ever feels remorse for their actions? Remorse seems to me to be an idealistic state, something that harps back to ancient times and has more to do with the sinner still getting a ticket into heaven than anything else. We are bullied and harassed to feel remorse as humans for all things judged immoral. But I think remorse rarely exists as a natural emotion, an unselfish emotion. Normally it takes punishment to feel remorse and when one feels remorseful under punishment and torture then it’s a selfish emotion to save oneself, relieve oneself of suffering. So the words above of Nilsen I don’t see as his. As we’ve already seen, his true words are suppressed and all that’s left that he can have published are words of remorse.

If you could speak to Dennis Nilsen or ask him anything, what would it be?

How are you? Health, well-being? Do you need anything? Can I help you in any way?