Windyheads Farm wasn’t on many maps and certainly not the ones the Germans were using in 1940.

It’s an isolated part of the north-east, eight miles from Fraserburgh and to the south-west of New Aberdour, with a small community which, despite hearing aircraft flying overhead, never expected to have any direct involvement with enemy troops during the Second World War.

Yet, on one foggy September evening in 1940, a Heinkel seaplane with three German airmen was caught up in horrible weather conditions and the crew struggled to maintain their bearings as they approached the coast.

It began with a doomed mission

Eventually, they decided the visibility was so poor they would have to turn back for home since they couldn’t carry out their reconnaissance mission.

But, for Hans-Otto Aldus, 23, Heinrich Kothe, 31, and Herbert Meissner, 34, their problems were only just beginning – because, when their manoeuvres in the darkness led to the wing tip of their Heinkel hitting the ground, it was the catalyst for the aircraft crashing to earth with a mighty thud.

And the ensuing events brought the war right to the gates of New Aberdour.

As the Germans tried to escape, Aldus suffered a broken leg and arm, while jumping clear from the plane, and lay on the ground in agony, just a quarter of a mile from Windyheads Farm and only 10 yards from the stricken craft.

The noise of the impact had aroused the attention of farmer Jimmy Beedie, 40, and work colleague Donald Watson, 31, who were inside the premises, listening to news about the Battle of Britain on their radio.

And then, Jimmy’s housekeeper, Agnes Kindness Marr, 20, who had been visiting her mother in the nearby village, dashed back to the farm and told the men about the crash, which prompted them to investigate the incident.

And, when they walked along the field edge of the Pennan to New Pitsligo road, Agnes discovered a pistol lying on the ground. She picked it up and the trio soon spotted the wreckage in the dim light of their lanterns and saw, to their horror, the distinctive black German crosses emblazoned on the plane.

The Scots were on their guard now and, as they approached the scene, noticed two figures in uniform crouching in a field, while the unfortunate Aldus was writhing on the ground. Immediately, Kothe cried out: “Kamerad, Kamerad, we are Germans, my navigator is injured….he needs a doctor”.

None of the Windyheads trio had any formal military experience, or access to a phone at the farmhouse, which might explain the subsequent sequence of events. While Jimmy left in pursuit of his motorbike to drive the four miles to the village for help, Agnes and Donald moved Aldus away from the plane in case it burst into flames – it was loaded with bombs – or exploded.

This was a desperate situation

Then, accompanied by Kothe and Meissner, they recovered a rubber dinghy from the craft in a bid to use it as a stretcher. It didn’t work. So Donald disappeared into the fog to look for something else which might do the trick.

And suddenly, equipped with only a lantern and the pistol in her pocket – which she had no idea how to operate – Agnes was left on her own with two Nazis, while her male colleagues were otherwise occupied.

Historian Alan Stewart has chronicled the drama in his two-volume North East Scotland at War and believes that Agnes behaved with remarkable calmness and decency in what were unprecedented circumstances.

He said: “She did not see them as enemies, just people in need of help. It would have been all too easy for the Germans to have shot her and escaped.

“The local policeman at New Pitsligo was 44-year-old Constable Harry Soppitt, who was asked by Jimmy Beedie to come with him to an air crash at Windyheads. Harry phoned in the report to Fraserburgh Police Station to request assistance, then set off on the back of Jimmy’s motorcycle.

“A short while later, two senior officers, Inspector George Michie, carrying a pistol, and Sergeant James Thomson, armed with a rifle, rushed over to the farm and the scene of the crash. (By this time) Donald, Agnes and Meissner had carried the injured Aldus to the farmhouse.”

The stage was set for a tense encounter between the respective parties. But, once again, it was young Agnes who rose to the occasion.

When Soppitt, armed with only a truncheon, arrived at the farm with Jimmy, he “was met with the sight of Agnes and a table of food for the armed German crew. Upon seeing the constable, they threw their Luger pistols on the table, indicating that they wanted to surrender.

“Soppitt was less than complimentary to Agnes, telling her there was a war on and food was scarce.”

And yet, reading the contemporary reports, it’s hard to shrug off the feeling this young woman might have prevented a bloodbath.

Agnes helped prevent bloodshed

As Mr Stewart added: “Armed to the teeth with guns and rifles at the ready, the local Home Guard, the two armed policemen from Fraserburgh, and local army officers arrived at the farm.

“But, expecting a shoot-out with hard-faced Nazis, they were astonished to find the airmen in deep conversation with Agnes.

“Doctor John Cameron from New Pitsligo and a nurse attended to Aldus and when they had done what they could, they waited for the ambulance to take him to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary some 40 miles away.

“Whilst he was going to the ambulance, Aldus gave Agnes a set of his binoculars and thanked her. These were promptly taken from her by the army officer who was escorting the airman to hospital.

“Kothe and Meissner were taken to Fraserburgh, where they spent time in the police cells, but not before Kothe gave Jimmy his cap badge as a thank you.

“Aldus was admitted to ARI on September 17 1940 and was placed under guard, not because he was likely to escape, but for his own safety.

“In the ward where he was taken were burned survivors from a ship attacked by the Luftwaffe and there was a risk of a lynch mob forming to seek revenge.”

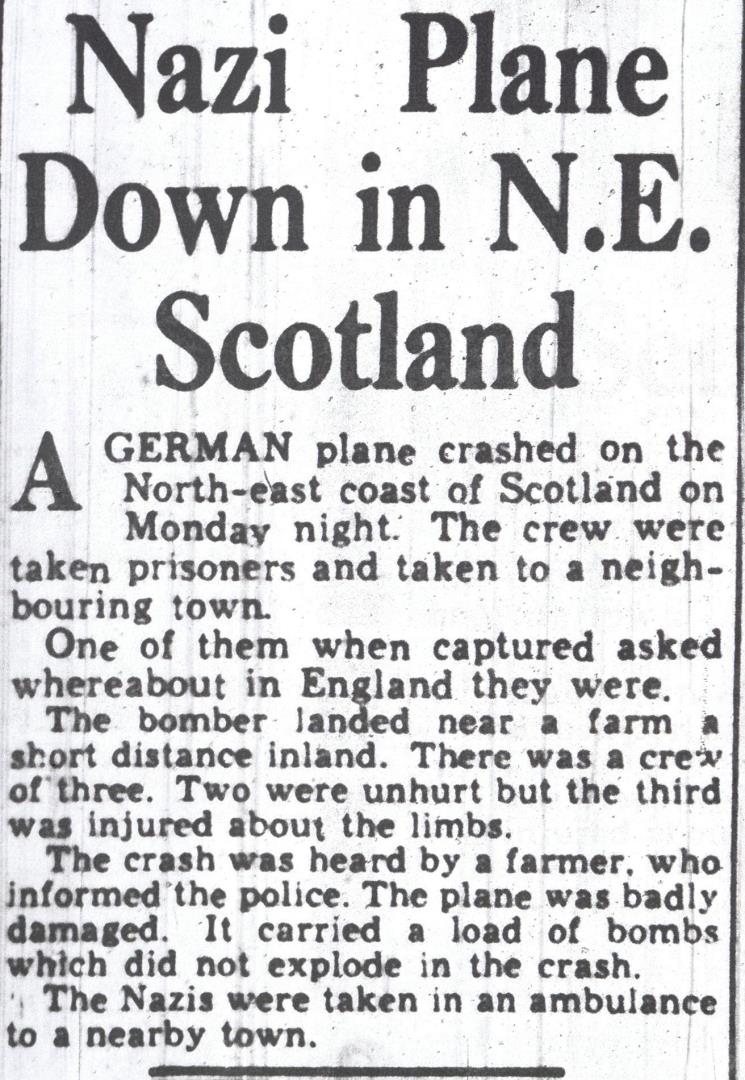

The Press and Journal carried details of the crash a few days later and reported that the crew had become so disorientated during the incident they had asked Agnes “what part of England they had landed in”.

Once officials from RAF Dyce had inspected the scene, a guard was created around the crash site, because the Heinkel was still full of fuel and had explosives on board. Yet, despite the cordon, “some of the locals managed to acquire a flare signal pistol from the area without being caught.”

What became of those involved?

As for the Germans, Aldus – who had made a favourable impression on most of the Scots he met – was transferred to a military hospital in Edinburgh, prior to spending the rest of the war in a prisoner of war camp in Cumbria, although his injuries continued to cause him problems for the rest of his life.

His colleagues were also interned, although Kothe was promoted in 1942 and it was only two years later that he was listed as a POW.

As for one of the police officers who attended the farmhouse, Inspector Michie had mixed fortunes during the conflict. In December, 1941, he was fined 2/6 at Fraserburgh Police Court for allowing a chimney fire at the police station to burn during the night: a breach which caused him embarrassment.

However, for his role in “maintaining morale and securing cooperation during air raids”, he was awarded the British Empire Medal in 1942 and received it from King George VI at an investiture service at Buckingham Palace.

He was a well-known figure in the region, cycling most days to the outlying stations of Rosehearty, New Aberdour, New Pitsligo and Strichen and visiting the Maud livestock mart every Wednesday.

The whole episode had positive consequences for two of the main protagonists, Jimmy and Agnes, who fell in love and married in 1941.

They went on to have eight children together and despite Jimmy’s death in 1980, his redoubtable partner became one of the pillars of her little community until her demise in 2007 at the age of 87.

For more than 70 years, the story of her courage and compassion during the war remained untold. But now Mr Stewart has set the record straight.

North East Scotland at War Volumes 1 & 2 can be purchased here.