A radical redevelopment of the beachfront. Dramatic changes for the city centre. A means of preparing Aberdeen for an unpredictable future.

The Granite City in 2022 is facing one of the biggest redesigns in its history, as the council presses forward with its masterplan.

But this is not the first time such wide-ranging measures have been considered.

Back in 1952, long before the foundation-shaking discovery of North Sea oil, officials in the local authority were grappling with how to modernise the city as they watched new industries spring up, old ones decline, and the use of motor cars explode.

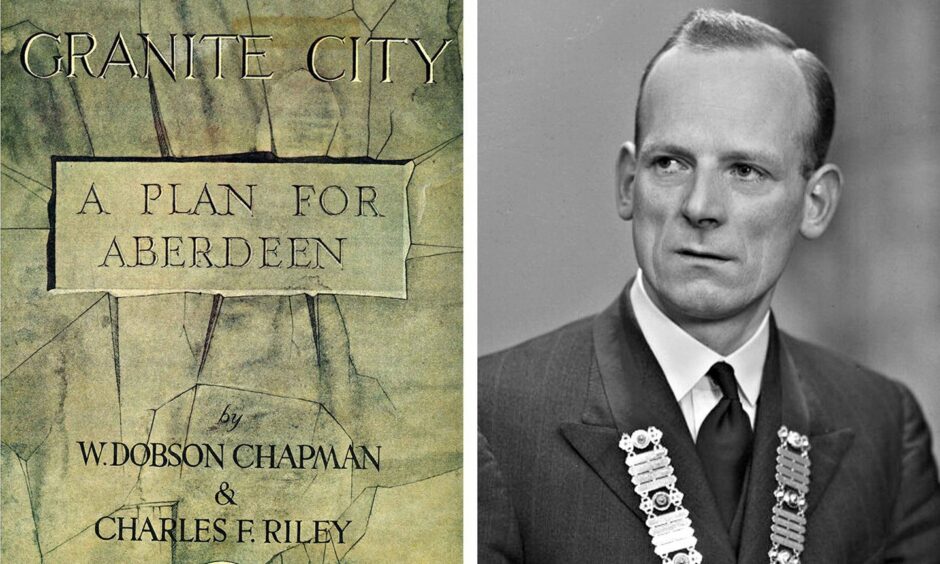

Two distinguished town planners named W. Dobson Chapman and Charles F. Riley were asked to identify problems and draw up proposals for how they’d fix them – with very few limits on how far they could go.

Eventually, they produced a large hardback book titled Granite City: A Plan For Aberdeen, filled with suggestions and drawings ranging from the brilliant to the baffling and bizarre.

And now, 70 years later, the Press and Journal has obtained a copy of the Aberdeen 1952 masterplan – and with it, a glimpse at what could have been.

- What would have been knocked down, and what would have stayed?

- How does it compare to today’s masterplan?

- Have any of its ideas been adopted?

- Why is one well-known local superfan so interested in it?

In their authors’ note, Chapman and Riley write: “It should be possible so to control the future development of Aberdeen that ultimately—even within the foreseeable future—it will approximate very closely to the planner’s specification for an ‘ideal city’.”

So what did their ‘ideal city’ look like?

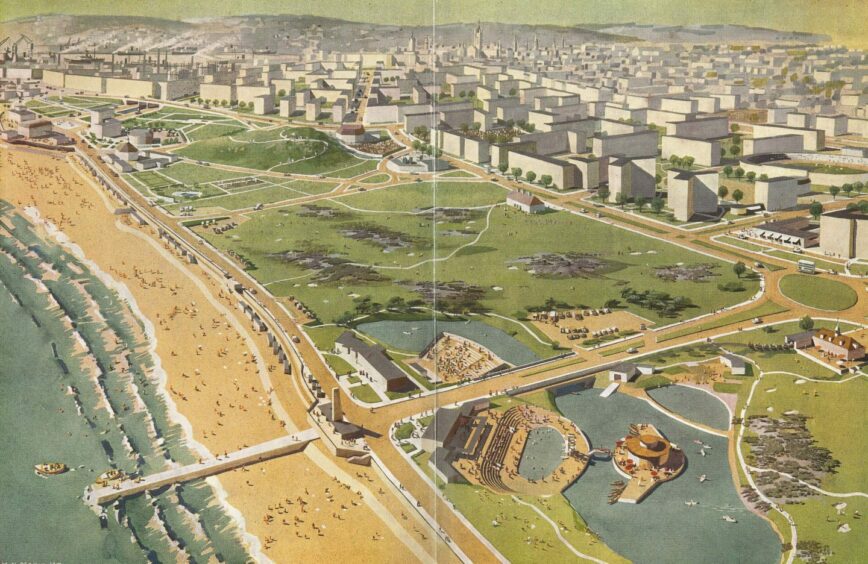

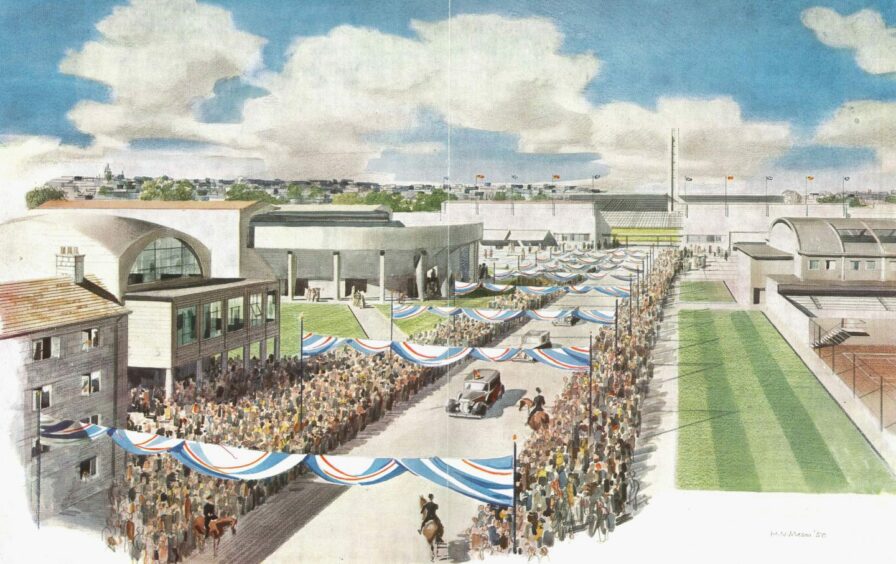

The beachfront reimagined

One of the most eye-catching artist visualisations in the book is saved for the centre spread, depicting the plans for the beachfront in an irresistible 1950s futurist style.

On what is describes in the caption as a ‘dead’ area – surely a surprise to the Kings Links Golf Course, which had already been on the site for 80 years by 1952 – there is a large manmade boating lake, bisected by a road bridge leading towards the Beach Boulevard.

A small island in the northern half of the lake holds a circular building, home to a cafe with umbrellas dotted outside.

Crossing back over the bridge would bring you to an outdoor swimming pool, complete with diving board and auditorium seating.

This, apparently, is one of two ‘beach centres’ providing open-air entertainment for locals and holidaymakers.

The critics of the modern-day cafe culture proposals might faint at such extreme optimism in the Aberdonian climate.

Time is a flat circle, as Rust Cohle from True Detective said, and there are indeed some echoes of the Aberdeen 1952 masterplan in the beachfront proposals unveiled last year.

A walkway leading out into the North Sea features in both, and there are similar patterns of crisscrossing routes – though in 2021 they are footpaths, and in 1952 they are roadways for cars. (Lending vehicles’ priority over pedestrians is a bit of a running theme in the earlier masterplan.)

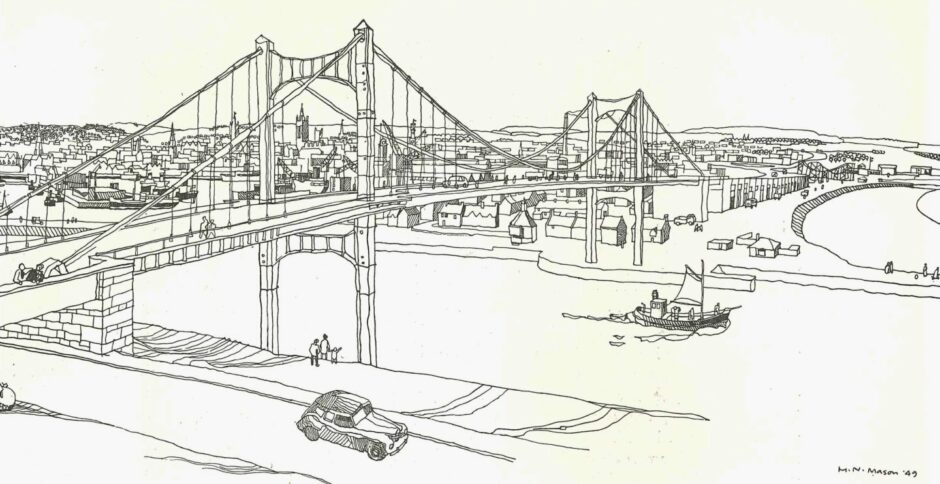

What would be done with the harbour?

Following the coastline south, we come to the harbour and one of the most drastic proposals offered by Chapman and Riley: a Golden Gate-style suspension bridge over the mouth of the port.

We are assured in the caption that it is “high enough to allow unrestricted passage to all shipping ever likely to use Aberdeen Harbour” – again, perhaps quite optimistic for a bridge that appears to cover a distance only around twice as long as the Bridge of Don.

“It is intended to provide a desirable north-south link on the eastern side of the city,” the book tells us.

“The striking views of the harbour, the city and the beach which could be seen from the bridge can well be imagine.”

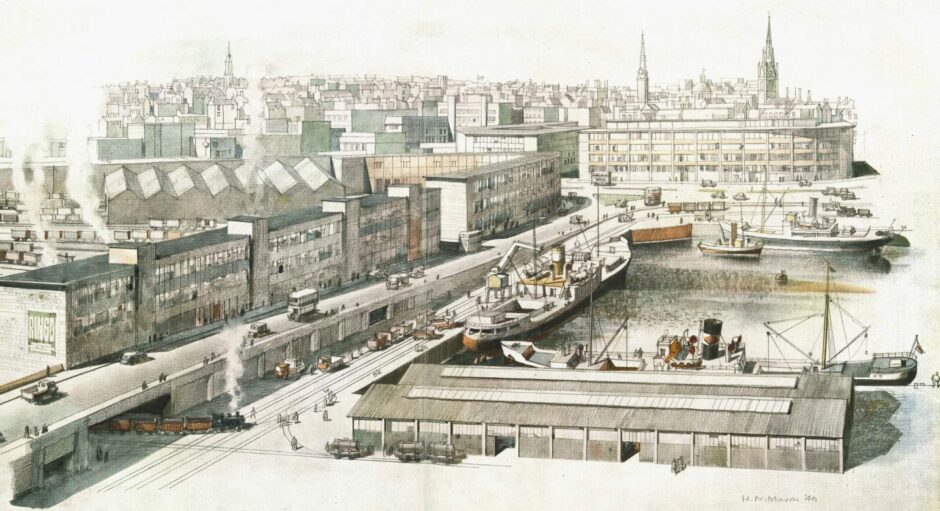

At the business end of the port, there is another radical transport solution with a proposed two-level redesign of Market Street.

As shown in a charming illustration marked with the year 1949, steam trains would chuff through tunnels below the raised street, allowing them to transport goods directly from the harbour to an expanded railway station which takes up the space now occupied by Union Square shopping centre.

How is the city centre shaken up in the plans?

Riley and Chapman do not pull any punches when describing the state of Aberdeen city centre in 1952 – and it’s interesting to consider the extent to which anything has changed.

“The existing road layouts of most of our cities leave much to be desired, and Aberdeen is no exception,” they write.

Which ideas from the 1952 masterplan would you like to see brought back? Let us know in our comments section at the foot of this article

“This is due very largely to the fact that the existing roads and streets were never designed for the type of traffic now using them.”

The Gallowgate and Hardgate date back to medieval times, they say, while Union Street, King Street and George Street popped up in the early 19th century, meaning “not one of the major streets in the Central Area was constructed after the introduction of the motor vehicle”.

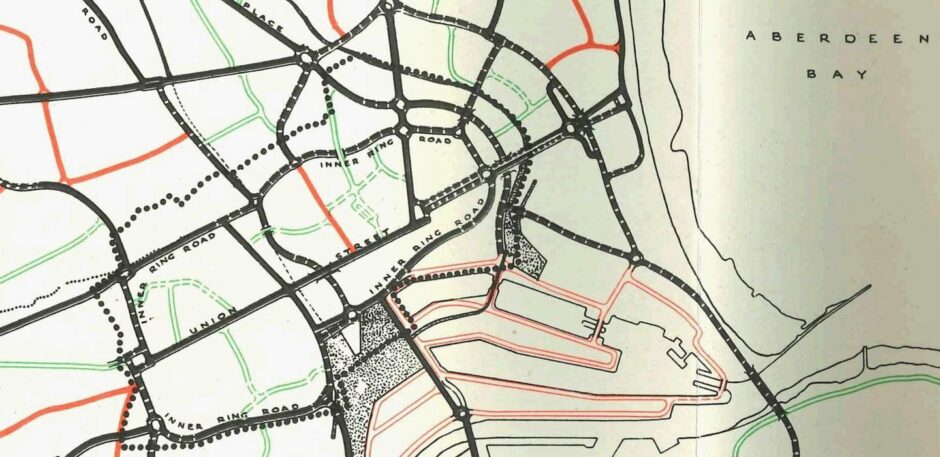

The “most significant” and “most urgent” proposal the pair recommend is the creation of an inner ring road, to alleviate the traffic on those major streets and “leave the Central Area free for the circulation of that traffic which alone has business to enter it”.

Incorporating routes including Guild Street, Virginia Street, Skene Street and Willowbank Road, the inner ring road as envisioned was never fully developed.

Many of the other dramatic parts of the plan are also focused on the city centre – such as getting rid of the Art Gallery and Central Library and bringing them together in a single building opposite Marischal College.

The iconic Salvation Army Citadel on Castlegate would also be torn down and replaced with a rather blocky Civic Centre, the new hub for council-related matters, and accompanying gardens.

What is the legacy of the 1952 masterplan?

From today’s perspective, much of the 1952 Aberdeen masterplan seems fanciful, as if it was too ambitious to ever have a chance of becoming real.

But Aberdeen Central MSP Kevin Stewart, who served as the Scottish Government’s planning minister for five years, says several of the ideas pitched in the document have actually come to pass.

He first laid eyes on the plan when local businessman John Michie showed him a copy during his time as a councillor. He became such a fan that his staff bought him Riley and Chapman’s book as a 50th birthday present.

“It’s probably one of the best gifts I’ve ever had,” he said. “It’s absolutely lovely to go and have a look at from time to time.”

In a parliamentary debate three years ago, he said he had a “love affair” with the document.

The MSP, currently minister for mental wellbeing and social care, believes the most tangible impacts of the masterplan can be found away from the eye-catching artist’s impressions.

He said: “Some of the more radical things – as some folk would have seen it at the time, though now we would say they weren’t radical at all – were probably in terms of the transportation side, and particularly the road side.

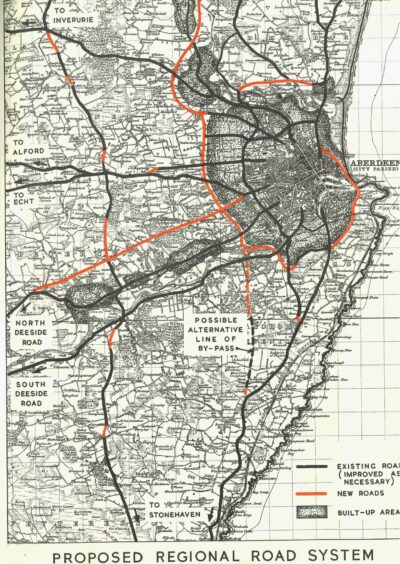

“Because they had in that masterplan what was the first major plan on paper for what we would now call the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route, which they termed as the outer ring road.”

The genesis of the AWPR, which opened to traffic in 2019, can be seen in the map of a ‘Proposed Regional Road System’ included in the book.

The route – described in rather flowery terms as a “desideratum” – differs significantly from the road that was ultimately built, skirting so close to the outer edges of the city that Hazlehead Park would be placed outside it.

But it shows a vision that would influence the future of the Granite City.

“That was there 70 years ago,” said Kevin, “and took decades to come to fruition.”

What was the fate of the masterplan?

Despite the success of some ideas, it is an unavoidable fact that Aberdeen does not look like it does in the stunning illustrations of the 1952 masterplan.

So what happened? What prevented the radical rethink from taking place?

For Kevin Stewart, the answer lies in the foreword to Granite City: A Plan For Aberdeen, written by Labour politician and wartime Secretary of State for Scotland Tom Johnston.

He writes in hope that “before long the innate good sense of the British people will enable them to short circuit the unnecessary delays caused by the red tape weevils, and planning will be given its rightful place in our affairs”.

The “red tape weevils”, then: it may indeed have been bureaucracy that ate away at the grand ambition of the masterplan.

But perhaps the proposals have not so much been dropped as adapted – until we arrived at today’s plans for a radical redevelopment of the beachfront, dramatic changes for the city centre, and a means of preparing Aberdeen for an unpredictable future.

It remains to be seen how the City Centre Masterplan of 2022 will be looked upon by Aberdonians in 70 years’ time, when that future comes to pass.

Conversation