When you look across the skyline of Aberdeen from a viewpoint, there are a few prominent buildings that rise above the complex of granite grey.

Several blocky high-rises, a few church steeples, and landmarks like Marischal College and the Sir Duncan Rice Library.

But my eye has always been drawn to Broadford Works, and the bizarre concrete column with the little circular hut on top.

At 65 metres, it’s one of the tallest buildings in Aberdeen. It also has a reasonable claim to being the city’s strangest.

Every time I looked at it, it seemed to make less sense.

Why did it only need windows at the very top?

Why was there a ladder to get up outside rather than anything inside?

What could have gone on in there?

Over the course of several weeks, I found the answers to all of those questions – and discovered that the round concrete tower at the Broadford Works may not just be unique in Aberdeen.

It might be the only one of its kind in the world.

A rich Aberdeen history

The Broadford Works tower was built in the 1960s, at a time of expansion for one of Aberdeen’s most storied companies.

The site had been home to the feverish industry since 1808, when Dundee-based Scott Brown and Co picked it for the construction of Scotland’s first iron-framed mill.

When economic pressures caused by Napoleon’s romp around Europe led the business to go bankrupt in 1811, Broadford Works was snapped up by Sir John Maberly MP.

Despite not visiting the city very much, Maberly was very popular in Aberdeen.

A lavish dinner was organised on one of his rare trips to the north-east, and a street was even named after him.

But Maberly’s dealings got a little murky later on, according to industrial historian Mark Watson.

He said: “In 1828, he claimed to have borrowed money from John Baker Richards, who had been governor of the Bank of England, and therefore Richards was sort of the owner of Broadford Works.

“In my opinion, Richards never went to Aberdeen and never knew he was the owner of this business.

“When Maberly declared himself bankrupt at the very beginning of 1832, Richards was probably already ill and wasn’t going to interfere very much.

“But the Maberly sign above the door was taken down and a Richards sign was put up, and it stayed as Richards for 160 years.”

The story of the concrete tower

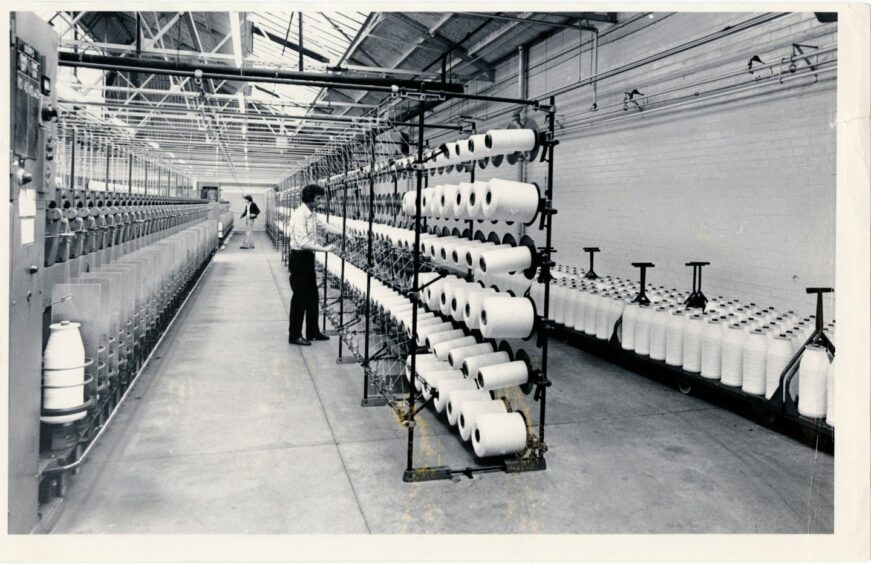

Richards and Co, produced all sorts of textiles at Broadford Works, from flax to carpet yarn.

But it was one product in particular that called for the construction of the concrete tower: hosepipes.

Alan Massie, who worked as an electrician on the site for 10 years between 1970 and 1980, talked me through the process.

“The hose department, that was something else for noise,” he said.

“You wouldn’t believe the noise in there.”

Weavers would use a circular loom to form a tube of linen known as a “catty’s tail”.

That process can be seen in a video from the National Library of Scotland, which also shows the concrete tower under construction.

The ‘tail’ would then be cut into 30m or 40m lengths and taken to the rubber department.

Alan said: “The first thing you noticed in the rubber plant was the smell of latex.

“It was really a strong, strong smell, and the heat in that place was phenomenal, and it was quite dusty.

“They used to take the hoses across there once they’d been manufactured.

“There they’d get them rolled out, sorted out into their groups, and this is when the towers would come in.”

When the towers come in

That’s right, towers plural. The round brick tower, originally a chimney, was converted for the same purpose as the concrete one.

Alan continued: “They took the hoses in, then they were attached by their couplers to a manifold, which was attached to a lift.

“This manifold was pulled up right to the top of the tower, and there were massive tanks of latex.

“If you imagine all the hoses being attached to this circular manifold, they would just run around the inside of the tower.”

As the linen tubes hung down the full length of the concrete tower, liquid latex would be pumped into them to line their insides and make them waterproof.

Then, once the latex had drained out to just leave a thin internal coat, a heating system would be turned on to bake the hoses until the rubber had set.

Height of terror

Why did it only need windows at the very top? That’s where the control room for the lift was.

Why was there a ladder to get up outside? Because the manifold would take up the full width of the tower inside.

Alan only climbed the ladder two or three times.

He said: “You had to climb up the outside on the ladder – without a harness, may I add – and if you ever look at the top part, there’s absolutely nothing round the ladders.

“If I remember rightly, I was only 19 when I was climbing up there, and you don’t have an awful lot of fear, but I remember the height and thinking, my God.

“You wouldn’t go up there on a windy day, put it like that.”

But the view from the top?

“You saw the whole of Aberdeen, aye. It was fabulous, absolutely.”

One of a kind?

So, was this a normal way of manufacturing hoses?

Well, no.

As this Youtube video shows, they are usually made by forming the fabric tube and the rubber tube separately, before the latter is fed into the former.

The far more complicated and labour-intensive Broadford Works method was not even replicated down the east coast at the McGregor hose factory in Dundee.

Mark, the industrial historian, said: “I’ve been researching the jute and linen industries, and I’m not aware of a tower that does that anywhere else.

“I think maybe it is unique for that purpose.”

What is next for the Broadford Works concrete tower?

Since Broadford Works closed in 2004, little has changed on the site beyond some vandalism and fire damage.

Planning permission for an ‘urban village’ was granted in 2016, and remains active though work is yet to begin.

While many of the old factory buildings would be demolished to make room for the development, the two towers and brick chimney – “an iconic industrial landmark on Aberdeen’s skyline”, according to the papers – would be kept.

However, there is no mention of what would be done with them.

Mark Watson’s idea is to transform it into a viewing platform, like the Smithfield Chimney that once belonged to the Jameson distillery in Dublin.

That way, the “fabulous” view of Aberdeen could be opened up to the public.

And after years of looking up at the bizarre concrete column, it might be possible to look down from the little hut on top.

Read more:

Conversation