There may be castles and battlefields, monuments and museums but 37 miles west of Aberdeen, the most historically important part of Scotland lies six feet or so beneath the grass.

It is here that scientists discovered and have been studying the 407-million-year old plant fossils that might hold the secret to life on earth.

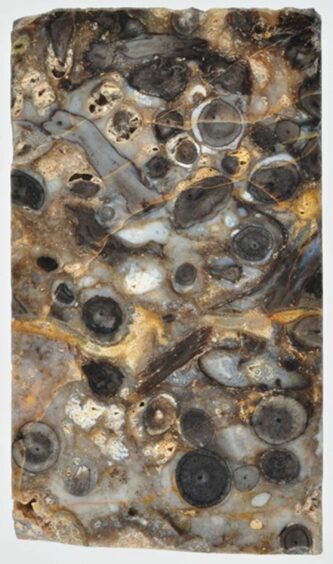

Known as the Rhynie chert, the rock’s fossils are evidence of the earliest known ecosystem of terrestrial life and wherever the plants grew on land, animals followed.

Scientists investigating how prehistoric lobe fish developed lungs and limbs to become

tetrapods – the ancestors of humans – believe it created a habitat, and potentially a food source, that may have lured the creatures from rivers and deltas on to land, paving the way for humanity itself.

The Rhynie chert was discovered in 1912 by Elgin medical practitioner Dr William Mackie. He had been geologically mapping the area around Rhynie when he found

some unusual siliceous rocks incorporated into a dry-stone wall field boundary. While

making thin sections of the rock, he observed perfectly preserved plant axes (stems)

showing detail of individual cellular structure.

Luckily, he realised the profound significance of this deposit and made his find known to specialist workers in palaeontology.

Oldest known fossil insects

Dr Sandy Hetherington, a palaeobiologist in the Institute of Molecular Plant Sciences

at Edinburgh University, has, for six years, been studying fossils from the Rhynie chert,

whose rock is made from silica (the same material as glass), and formed from hot volcanic springs. It contains plants with beautifully preserved cells, primitive spiders

and the oldest known fossil insects.

He said: “The Rhynie chert is in a field grazed by sheep. It is designated as a site of special scientific interest (SSI) but there are no signs and if you walked past, you wouldn’t see it.

“What that actually shows us is what a terrestrial ecosystem at that time looked like.

“This is the earliest time we have early plants and animals on land in a complex ecosystem anywhere in the world.

“What is particularly interesting about this site is many of the plants are very small, so if we are thinking about that tetrapod transition, one of the reasons that this didn’t happen earlier is that there might not have been a terrestrial ecosystem and flora and fauna that could actually have sustained a large fish at that stage.

He continued: “Scotland is key when you are talking about humankind being

here as a result of the tetrapod transition. Scottish fossils are key to the evidence that

we have with the early plants establishing a terrestrial surface where the animals can survive.

“And sites like the Rhynie chert are giving us remarkable insights that we are not getting anywhere else in the world.”

First colonisers of land were plants

The university’s professor Steve Brusatte, a vertebrate paleontologist and evolutionary biologist who specialises in the anatomy, genealogy, and evolution of dinosaurs and other fossil organisms, said: “The first colonisers of the land were plants, and they

built the ecosystems that then attracted animals that came out of the water, and from there developed the hugely diverse jungles and rainforests and plains and tundras and other land ecosystems of today. None of this would have happened without those pioneering plants.

Scientists from the National Museum of Scotland – which also holds samples from the chert – are part of an international and multidisciplinary consortium researching exactly how prehistoric lobe fish over millions of years developed limbs, lungs, digits, necks and hips as well as a specially adapted circulatory system and senses that made possible their move to land.

Food on land that attracted them?

The museum’s Department of Natural Sciences head, Dr Nick Fraser, who specialises

in vertebrate palaeontology, said: “Was it because there was a food source on land that attracted them? What was pulling animals, which were adapted to living in water, to this harsh environment on land? We know there has to have been a rich food source on

the land because we have the Rhynie chert.”

And while scientists don’t have a definitive answer, he says, they are certain “the rich geology of Scotland gives it a central role in the understanding of the evolution

of terrestrial life on earth.”

“The clues to the tetrapod transition could well be in Scotland,” he said, explaining

that eminent scientists in the field are “drawn” here because of the country’s “incredible

collection of fossils from this key time period”.

Conversation