Six months ago, Robin Grant was lying on an operating table on the brink of death as a flesh-eating bug took over his body.

As medics began to cut away the infected tissue, the 42-year-old fitness enthusiast – who had never taken a day off sick in his working life – was close to suffering total organ failure and toxic shock.

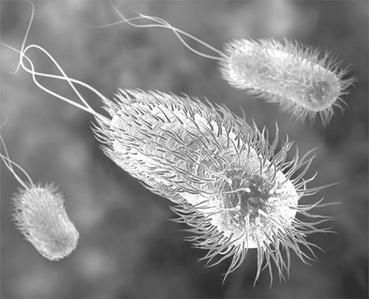

Some victims of the invasive bug – necrotising fasciitis – will not last 24 hours, while most who contract it will not live beyond four to five days.

Mr Grant had lasted a week – and the consequences of such late medical intervention were severe.

Before he was sedated, he was told that if he wanted to say goodbye to his family, now was the time.

“If there’s one thing I will remember to my dying day, it’s the doctor saying that if I’ve got any phone calls to make, to go and make them now,” he said.

Aberdeenshire-born Mr Grant, who now lives in Inverness, contracted the infection at the end of August, first realising something was wrong when he woke up in the middle of the night with a sore shoulder.

He was given painkillers, but as the week progressed it became clear something was very wrong.

“I was physically sick and I couldn’t walk,” he explained.

“My dad came to Inverness to pick me up and take me home as I was struggling.

“When it got to the stage where I could barely stand, I went to see a doctor in Insch. He took one look at me and sent me straight to A&E.”

Mr Grant was in surgery at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary for the next three days as doctors battled to stop the infection from spreading.

They were able to finally diagnose what was wrong with him by carrying out an ultrasound.

“There are a few tell-tale signs, but one of them is to carry out a scan that will pick up gas bubbles underneath the skin. It’s the flesh dying,” he said.

“They say that if you put the bug on a slide in the lab they can see it moving very fast.

“The only way to treat it is to cut it out – there’s no medicine.”

The next thing he remembers is waking up two weeks later, and seeing his twin brother, Corin, by his side.

He said: “I was so confused as he lives in London. I had no idea what he was doing here.

“As I came round, it began to sink in what had happened.”

Doctors had to cut away most of the tissue and muscle from his right upper arm, shoulder and chest. He will never have full function in his arm again.

“The first thing I did was check that I had both of my arms, as they thought I might lose one. Thankfully they managed to save it,” he said.

Mr Grant was transferred to the hospital’s plastics reconstruction ward where medics continued to wash his wounds and build him up.

Together with countless blood transfusions and intravenous antibiotics, the plastic surgeon looking after him used a revolutionary type of skin graft – often referred to as “shark skin” – to patch up his wounds.

The artificial skin contains a substance made from shark cartilage and also collagen taken from cows’ tendons to help regenerate blood and skin cells.

Mr Grant said: “There’s a lot I do remember from hospital which I wish I didn’t. Some of the images in my head now will never go away.

“The nurses would have to change my bandages quite regularly and help me shower. They would take the dressing off and I would see my ribs with bits of flesh in between.

“There’s no muscle left. It’s just skin on bone.”

To this day, Mr Grant has no idea how he contracted the disease. Neither do the doctors who treated him.

“People ask me how I got it and I can’t tell them, I don’t have a clue,” he said.

“You can pull a muscle and it will get in. You can have an insect bite or scratch and it will.

“I can only put it down to bad luck.”