As Bob Owen gazed across the upper deck of HMS Anson, it was not uncommon to find a 16in coating of sheer ice had accumulated while the battleship ploughed its way through Arctic slush.

And the stunning aurora of the night sky did little to detract from the fear of death which haunted him and his comrades day and night.

If a German torpedo struck their ship, they could sink within minutes and in the freezing waters of the Arctic Circle men perished in moments.

Mr Owen, now 89, knew this better than most.

The World War II and Arctic Convoy veteran from Aberdeenshire had seen the lethal affects of the ice-cold sea first hand during a rescue mission on board a Royal Navy destroyer off the Norwegian coast.

Speaking from his “second home” at Westhill’s Men’s Shed, Mr Owen said: “The ship I was on recovered some blokes on a boat and when they got them on board it was very difficult.

“All their clothes were frozen, and we were frozen because the temperature was so low.

“We were hurting them as we brought them on board. One of the guys died on the ship and we were told one of the boys lost his fingers and toes.”

Dangers such as these were ever present for the brave sailors of the Arctic Convoys – a mix of Royal Navy, US Navy, Royal Canadian Navy and Merchant Navy ships, which provided vital supplies and ammunition to the Russians during WWII.

And now – 70 years on from the Allied triumph – Mr Owen’s courage has been recognised with an invitation from the Russian government to St Petersburg to mark VE Day on May 8.

It will be a proud moment for the Westhill veteran, who started his Royal Navy traineeship in Upper Kent in 1941, aged just 14, having set his sights on the service from a very young age.

Today, as he holds a picture of his teenage self sharing a joke with his fellow young sailors, Mr Owen reflects on just how lucky he is to be attending the anniversary commemorations.

“A lot of these lads were killed during the war,” he said. “There was only one I know who lived.”

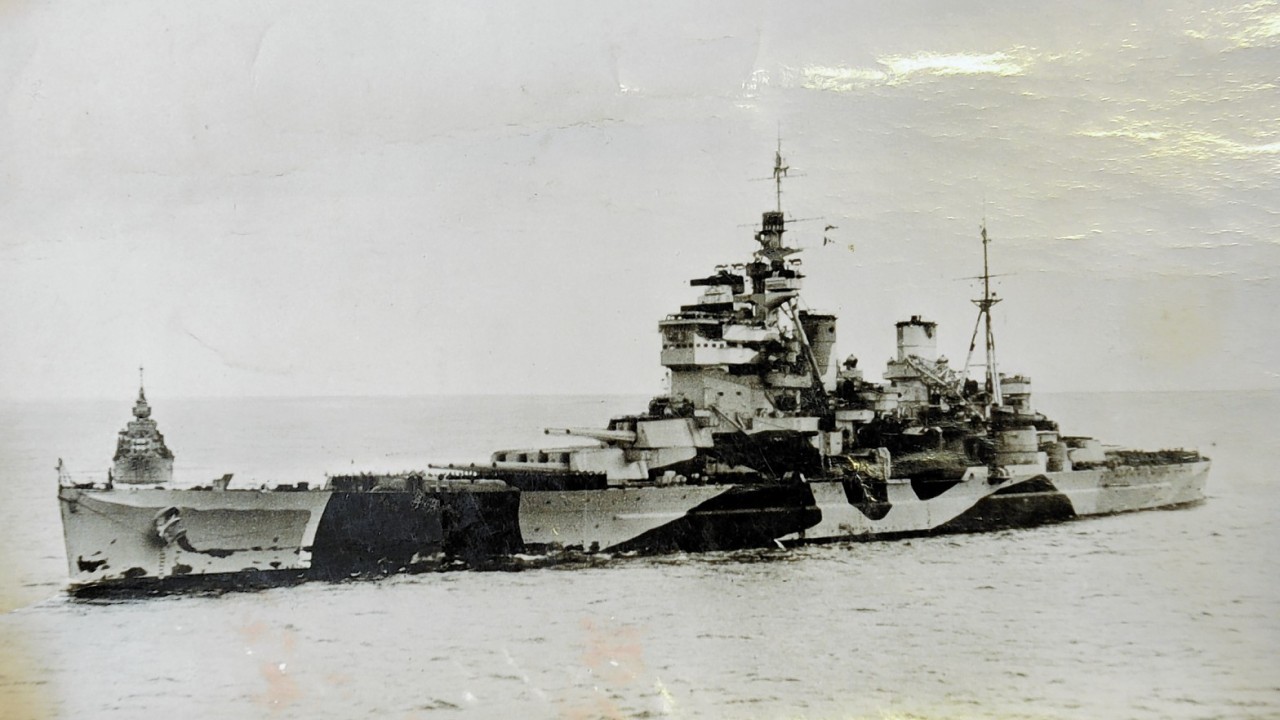

Aged just 15, he advanced to the Royal Navy in February 1941 and was assigned to HMS Anson at the start of 1942.

His memories of the battleship and life on board it are still pin sharp.

He said: “The ship was built on the River Tyne in Newcastle. It had 10 by 14 inch guns, their maximum range was 19 miles.

“We used to muster on the upper deck at 8am every morning on the Tyne. We were there one morning when a huge explosion in the river took place.

“They reckoned a mine had been dropped and of course we all flattened on the deck. That was my first taste of war.

“Once we had finished our trials we went into Scapa Flow and started in the Russian Arctic Convoys. We used to patrol behind the convoys up and down the Norwegian Coast.”

HMS Anson assisted a total of nine Russian convoys between 1942 and 1943, sailing along the treacherous coast of German-occupied Norway, where Nazi warships loomed around every fjord.

As a seaman, Mr Owen’s first job was as a forward look-out. He later progressed to the ranks of ordinary seaman and torpedo man.

He recalls gruelling conditions and little in the way of comforts.

“The upper deck would be just covered in ice, mostly about 16in thick, it was solid,” he said.

“I remember how cold it was, the sea was solid and we had ice flows going on. It was often -30C.”

He and his shipmates lived under constant threat of torpedo attacks from German ships.

“You were always on your toes,” he said.

“Being in a danger was like that – all the time in a state of alertness – but you live with it and you try to do a job.”

The convoys sailed from North America and Iceland to the ports of Arkhangelsk and Murmansk, in Russia, carrying vital supplies to the Soviet Union.

Then prime minister, Wintson Churchill, labelled the routes “the worst journey in the world”.

Temperatures were so low that touching surfaces could tear the skin while the cold led to equipment frequently malfunctioning.

When seas were high, waves landed on decks as solid ice and had to be scraped off immediately as they heightened the risk of capsizing.

Following the Arctic Convoys, Mr Owen took part in others across the Atlantic and patrols in Gibraltar, North Africa and West Africa.

By the end of the war he was a leading torpedo operator, and in total he served 15 years in the Royal Navy before pursuing a career as a computer engineer.

He married wife Vera – who died two years ago – on April 13, 1946 after meeting her in Eastbourne.

And while he misses the camaraderie of life on the high seas, he has found a “new lease on life” on the brink of his 90th birthday – thanks to the workshop and social area at the Men’s Shed.

Mr Owen said: “Here it is just like being in the mess again. We work in the workshop together and chat, I have got a second life up here.

“I never thought I would live this long. I saw all the boys who formed the British Expeditionary Force before they went to France and most didn’t come back.”

In total, 3,000 Royal Navy and Merchant Navy sailors died on the convoys and 101 ships were sunk.

However, their courage contributed to the delivery of more than four million tonnes of cargo, including 5,000 tanks, 7,000 planes, fuel, medicine and raw materials.

A total of 78 convoys launched between August 1941 and May 1945.

The supplies they carried played a vital role in Russian forces defeating the Germans on the Eastern Front, which led to the collapse of the Third Reich and the Allied victory.