Jackie Stuart was surprised by all the fuss which surrounded him when he was released by the SAS from a lengthy siege at Peterhead Prison in 1987.

During his five-day ordeal, he was kicked, punched, threatened with being set on fire, stabbed several times, and warned by some of Scotland’s most dangerous prisoners that if the authorities messed them around, he would be facing his Maker.

It was one of the most notorious incidents in the history of the prison, nicknamed the Hate Factory, yet when Jackie was eventually freed, one of his first thoughts was how quickly he would be able to return to work. And six weeks later, he was back.

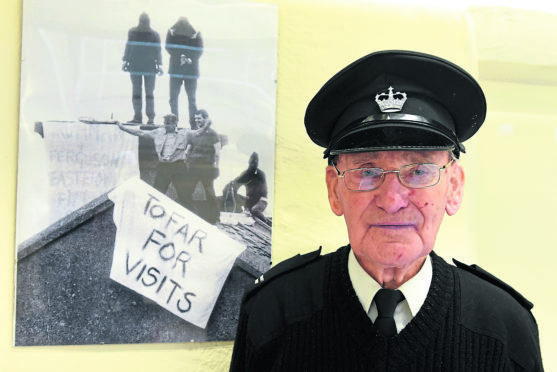

Jackie was still volunteering in his 90s

Mr Stuart, who has died at the age of 93, later wrote about his experiences, but the father-of-six never allowed the incident to define him or make him afraid to enjoy life.

On the contrary, when the prison, dating back to 1888, eventually closed in 2013, he was among the pivotal characters who helped transform it into a museum – and, even in his ninth decade, he volunteered to take visitors on tours of the premises.

Large parts of his life were spent in the company of depraved men, who had committed the most horrific crimes, but this level-headed north-east fellow with a dry-as-Nevada sense of humour carried out his work calmly and methodically, whether in Peterhead or at the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland’s notorious Maze prison in the 1970s.

He occasionally wrote letters to girlfriends and wives on behalf of those who were behind bars and found himself being asked to scribble down: “Love you, pet” and other romantic messages from prisoners.

He recalled: “It was a bit strange sitting with a hard man and reading out: ‘Hello darling’, and then writing back: ‘Hello sweetheart, dearest, etc,’ not words I would have thought these men were capable of using. But I did it and they were grateful.”

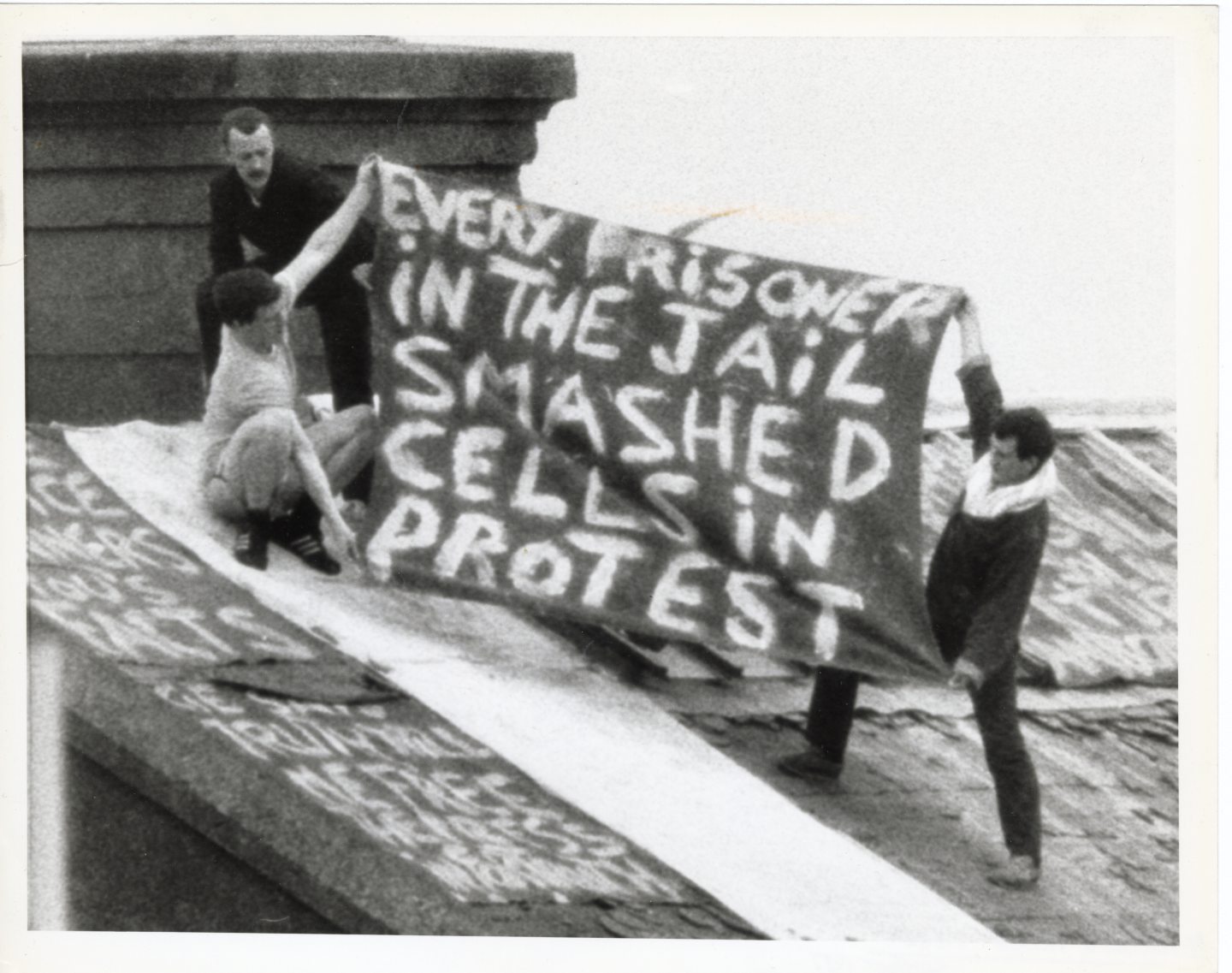

Prison siege made international headlines

However, events in September and October 1987, propelled the warder into the global spotlight after a riot erupted in D-Wing.

Mr Stuart told the Press & Journal: “A colleague [Bill Florence] had placed an inmate on a minor report in the morning, but in the evening, when they [the prisoners] were out for leisure, the inmate tried to stab the officer who was involved.

“I went to his aid, but after wrestling him to the floor, I noticed the whole hall had become involved in the incident and events just spiralled from there. My attitude to life is that if something happens, it happens, and you have to make the most of the situation. I always look on the positive side of things, and that kept me going.

“But, because one of the group of inmates [Malcolm Leggat] could best be described as erratic, there were times when I was unsure how events would unfold. My focus throughout it was to try and keep everybody calm and not inflame the situation.”

Desperate men with nothing to lose

The ringleaders in the riot included individuals as Sammy “the Bear” Ralston, Douglas Mathewson and Leggat, who were determined to cock a snook at the authorities and weren’t too choosy about the tactics they employed.

After seizing Mr Stuart, they moved to an area in the roof space of the prison and created a variety of barricades and booby traps, using such items as burning bedding and soiled sheets to ensure nobody could get near them.

When news spread of the crisis, the BBC screened footage of him being hauled on to the rooftop, where a hooded prisoner swung a weapon at his head.

Then, as September turned into October, the story had commanded the international headlines and prime minister Margaret Thatcher decided the stalemate could not be allowed to continue.

It was at that point, as pressure increased for an end to the impasse, that the prison authorities liaised with senior politicians and the SAS’s involvement was sanctioned.

SAS team called in to end siege

At the start of October, about 20 men from the SAS’s on-call anti-terrorism team were flown from RAF Lyneham in Wiltshire in a Hercules aircraft to Aberdeen, before being driven under police escort to Peterhead Prison, where they prepared for their response.

Mr Stuart had no knowledge of these developments and admitted that being left in the dark was beginning to take its toll, especially given the volatile nature of his captors.

He said: “This was possibly the worst part of the experience, because I had no idea that they would be coming in, and when the stun grenades and tear gas were thrown in, it took me by total surprise, as it did the inmates.

“But the speed and professionalism they displayed was really impressive. I was removed from the scene by an SAS officer and ran back along the roof to a rope, which then led me to a ladder, which took me to another SAS officer and to safety.”

‘I just got on with things’

This was in the days before there was any real recognition of post-traumatic stress disorder and Mr Stuart received little more than a physical check for cuts and bruises, prior to returning to normal prison duties in November, 1987.

His response perhaps summed up why he seemed so unperturbed. As he commented: “Well, it was part of my job, I just got on with things.”

And when asked if he was scared about returning to the place where his life had been placed in serious jeopardy, he added: “No, definitely not. I’m thrawn, you see.

“I don’t like to get beat. They might have beaten me up, but in the long run they didn’t beat me, they didn’t win. I went back to my family, they went back to their cells.”

Volunteering at the museum

It didn’t seem surprising in the slightest to discover Mr Stuart in his element after returning to his old haunt when the prison museum opened in 2016. And, even as he reached his 90th birthday on Boxing Day in 2020, he was still sufficiently fit to be one of the most popular figures for the many tourists who visited the site.

The pandemic closed everything down for a while, but Jackie was still a regular attendee at the site when it reopened in the aftermath of Covid and said with a twinkle in his eye: “Being involved since day one of the museum project has been enjoyable and it is great to see what a huge success the whole development has been.

“Meeting such lovely visitors is a huge difference to my former life inside these walls. It is terrific somebody did this at the prison, because it was just lying empty.”

He loved this development in the autumn of his life. And the staff loved him back. Jackie was even awarded an MBE in 2021 for services to volunteering.

‘Thank you for everything’

Alex Geddes, operations manager at the museum, said on Tuesday: “Visitors from across the world loved it when he was on site and for them to meet him in person after the tour was the icing on the cake.

“His strength of character and fortitude set the bar for many of us here to try and emulate but none of us could ever quite make it.

“That said, Jackie was always there to encourage all our team and he was never short of coming forward to share his experiences with us but in a pragmatic and humble way.

“Until we all meet again, my friend, thank you for everything you have done for us.”

Many people will share these feelings. Because one of the special things about Jackie Stuart is that he never regarded himself as special at all.