It was Britain’s biggest maritime disaster – claiming more lives than the losses of the Titanic and Lusitania combined – yet the fate of HMT Lancastria remains a mystery to most people today.

Now, as commemorations were being held yesterday to mark the 75th anniversary of her wartime sinking off the coast of France, an artefact from the doomed ship has surfaced in an Aberdeen suburb.

Former pub landlord Lenny Bleakley, 67, was astonished to read about the scale of the disaster, which is believed to have killed at least 4,000 servicemen and civilians, and realised he had his own piece of history at his Bucksburn home in the form of an authentic set of ashtrays from the ship.

Mr Bleakley got the collectible 15 years ago following a chance encounter with a customer at Culter’s Richmond Arms, which he ran until retirement three years ago.

He said: “We used to have this guy come into the pub sometimes with bits and bobs he’d swap for tobacco or a drink.

“One day he comes in with this ashtray and I gave him an ounce of tobacco for it.

“It was only when this guy from the Merchant Navy came in and told me about it that I realised the history.

“I think it must have been stolen by someone on the ship, it’s funny to think it got all the way up here though.

“I’ve had it for years but it wasn’t until I was reading about the sinking in the paper I thought that some people might be interested.”

He is now appealing for anyone interested in the ship’s history to contact him on 01224 912165.

Known as Tyrrhenia when she was launched in 1920, the 16,000-ton Clyde-built Cunard liner was taken over as a troop ship in 1939, when she was renamed Lancastria.

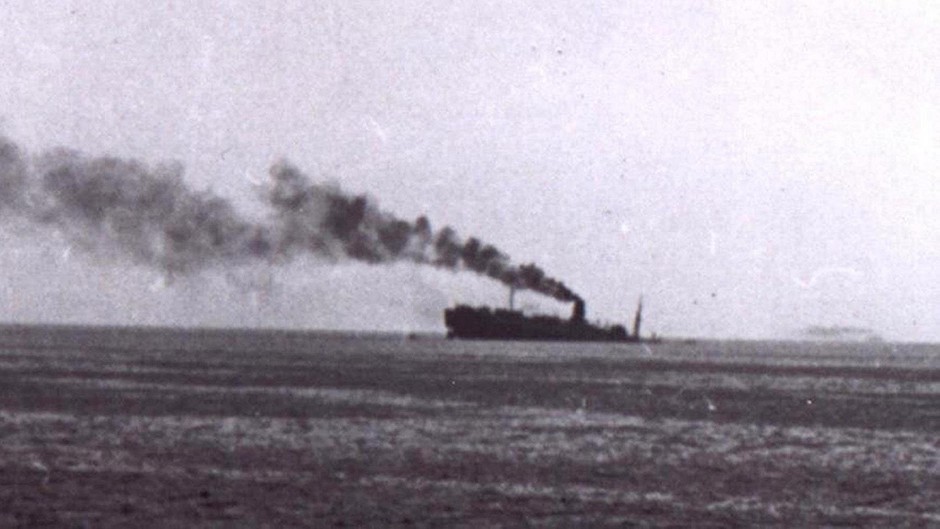

Her place in history was cemented in the early hours of June 17, 1940, after thousands of British military personnel and civilians being evacuated from France climbed aboard as she was anchored a few miles outside the French harbour of St Nazaire.

Just before 4pm, the Lancastria was hit by bombs from German aircraft, causing the ship to sink.

Meredith Greiling, curator of maritime history at Aberdeen maritime museum, said: “The sinking is especially tragic because so few people know about it.

“It came soon after the Dunkirk evacuation and French capitulation so Churchill thought it was best to keep it quiet from the public.

“It has stayed that way to this day in the public imagination.”