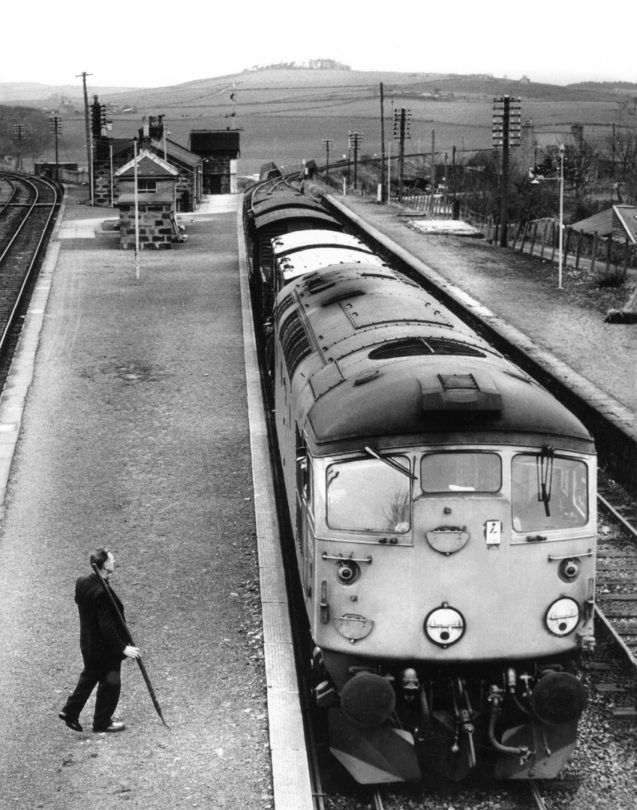

It’s become fashionable to blame Dr Richard Beeching for the devastation wrought to Scotland’s railways in the 1960s.

His name is inextricably linked with the word “axe” after he published his infamous report which sparked a major series of route closures and cuts across the Highlands and the north east as part of the restructuring of the nationalised system.

These included the hammer falling on services from Aberdeen to communities such as Fraserburgh and Peterhead, for which the death knell sounded in 1965.

Yet, a new book by transport expert, David Spaven, has laid bare that the much-maligned Beeching wasn’t always wrong in his decision-making process.

Use it or lose it was the message

Sometimes, it was the lack of passengers which settled a service’s fate.

And, while there are calls to revive the Buchan line, the statistics offer a cautionary tale of how more people liked the idea of trains on their doorstep than actually using them.

The Formartine & Buchan Railway originally opened to the Blue Toon in 1862, striking off from the Aberdeen-Inverness line at Dyce, before heading north to Ellon and Maud, where it turned abruptly eastwards.

The 16-mile “branch” from Maud to Fraserburgh started operations in 1865 and these were significant links across the area for the next century. Yet they were struggling to cope with increasing car usage and alternative bus services by that stage.

They could have fitted in a taxi

In Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines, Mr Spaven has explained how near-empty trains made expensive journeys from Peterhead to Aberdeen and back every day.

And, although there was a public outcry when the Beeching Report was initially released in 1963, it did nothing to halt the once-popular lines being scrapped.

Mr Spaven said: “The front page of the Press & Journal on March 28 1963 was full of reactions to the Beeching Report, with one of the more melodramatic of the many headlines being: New Highland Clearances are Feared.

“Fraserburgh – with its trains to Aberdeen being significantly faster than the bus – had much more to lose than Peterhead with its circuitous rail route.

‘These cuts will harm us’

“Under an editorial page headline Broch Provost – Doom If…, Fraserburgh’s provost Alex Noble commented: ‘We did not expect cuts on this scale.

“We are one of the highest areas of unemployment in the country and this will mean that more men will be out of work unless the railways in their wisdom have alternative work for the men who will be out of a job.”

However, British Rail’s Heads of Information provides a detailed statement of the numbers of passengers using the Peterhead trains ‘on representative days’.

With just three trains on weekdays from Maud to Peterhead (connecting out of services from Aberdeen to Fraserburgh) and four in the opposite direction – supplemented by a summer Saturday train in each direction – it was little surprise that numbers were low.

And if you factored in the circuitous rail route compared to bus or car journeys, and the need to change trains at Maud, it is little wonder the Peterhead route was unprofitable.

The numbers simply didn’t stack up

Mr Spaven said: “During the winter, a total of 30 passengers travelled daily in each direction on Mondays to Fridays, and 40 on Saturdays.

“In the summer these figures increased to 50 on Mondays to Fridays and to 60/80 on Saturdays. But the busiest train – the 3.20pm from Peterhead to Maud on summer Mondays to Fridays – averaged only 25 passengers.

“And the three quietest trains had three or four passengers: just a taxi load.”

Just three months after the publication of the report, a statutory British Rail public notice announced specific closure proposals for the lines to Fraserburgh, Peterhead and St Combs (and no fewer than 23 other stations served by these routes).

This led to a warning from the Peterhead Provost, Robert Forman, about the consequences of the Beeching scythe casting a blight on the region.

He said: “It is the easiest thing under the sun to close down the railways, but it takes a really big man to find a way of maintaining them.”

Mr Spaven told me: “It is not fashionable to say so, but, in some ways, Beeching has had an unfair press.

“His promotion of fast inter-city services, ‘merry-go-round’ coal trains from colliery to power station and the pioneering Freightliner (container-carrying) concept took the railway in the right direction, all proving their worth in subsequent decades.

His name is synonymous with the axe

“But it was the closures – not intangible concepts, but threats to the life of places where people lived, worked or holidayed – which defined Beeching’s image in the public mind.

“As I argue in the book, the route to Fraserburgh – which saw a strong campaign against closure by local people and the National Union of Railwaymen – should have been reprieved, rationalised and developed as a key transport link for Buchan.

“Beeching was right about Peterhead, but he definitely got it wrong on Fraserburgh. And today, a new railway, initially to Ellon, and then onwards to Peterhead and Fraserburgh, should be Scotland’s top-priority rail re-opening project.

“Of the 40 or so routes slated by Beeching for passenger closure in Scotland, only nine were reprieved (including Inverness to Kyle and Inverness to Wick and Thurso).”

These included the former Highland Main Line from Aviemore to Forres, via Grantown-on-Spey and Dava Summit; the Speyside Line, the Moray “Coast Line” and the Keith-Dufftown-Elgin “Glen Line” in the north east.

And it spelled the end for the double-track Strathmore Route, where Glasgow-Aberdeen expresses traversed the fastest stretch of railway anywhere in Scotland.

The oil boom arrived too late

We shouldn’t forget this happened only a few years before the discovery of the Forties Field in the North Sea in 1970 and the subsequent explosion in the oil and gas sector.

That would have opened up new markets and probably been the catalyst for an upsurge in passenger numbers and enhanced quality of services and infrastructure.

However, bold plans are in place for a revival of parts of the Buchan line. Now, it’s about finding the investment to bring them to fruition.

Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines is published by Birlinn.

Conversation