Whether on land, sea or abroad, danger seems to be Jim Still’s constant companion.

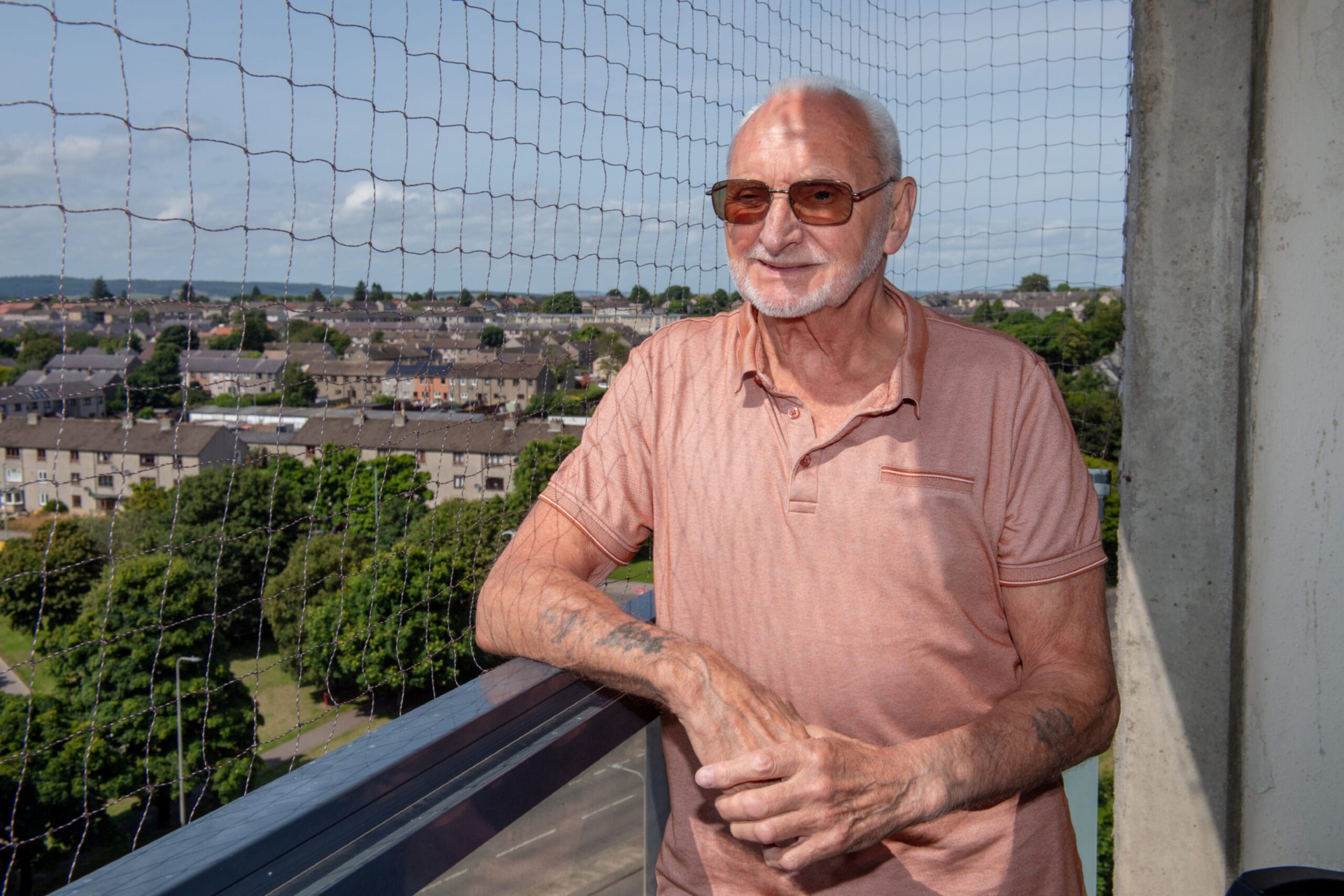

Leaving school for the British Merchant Navy at 15, the Foresterhill resident has taken on a series of high-risk roles in his lifetime, some leaving him with a broken back or staring down the barrel of a gun.

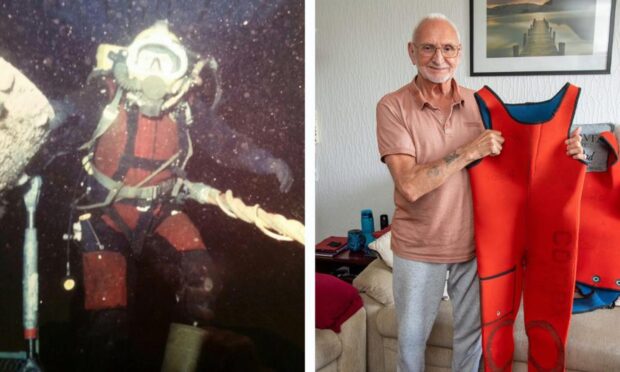

So when asked about one of his most risky jobs as a civil engineer in harbours and then as a deep sea diver in the North Sea, his casual response should have come as no surprise.

“I guess some of the jobs were dangerous,” said Jim. “The worst you could do was make a mistake with the explosives.”

He went on with a cheeky grin: “I used to use my teeth to bite the detonator instead of using the pliers.

“I did that until I saw one of the crane men, he had half his fingers missing.

“He’d been playing with a detonator. So I stopped biting after that.”

‘When I used to go offshore I would have it in my mind that I might not come back’

Since 1966, it is estimated that 79 divers have lost their lives in the North Sea oil and gas industry.

In order to recognise these lives, former saturation divers Nick McClellan and James McLean announced their intention to raise money for the creation of a memorial in Aberdeen last year.

Jim’s own circle of friends was not unaffected by these statistics.

A terrible accident

Losing several former colleagues to suicide, another friend, William Crammond, was killed in one of the most terrible accidents in the history of modern commercial diving which later came out was due to faulty equipment.

Jim said: “Billy was on the rig that took the clamp off the chamber and everybody inside was blown to bits.

“He was the guy who opened the clamp and the sledgehammer went through his head. He was killed instantly and the four guys inside were just incinerated.

“They found out later that the gauge for the hub was broken. It had been reported weeks before and it had never been fixed.”

Close calls played on Jim’s mind

While the job has changed in many ways, it is still considered a hazardous field.

Just last month, 900 North Sea divers voted for two months of strike action due to the hazardous conditions divers are working in with pay falling behind in real terms.

For Jim who trained to become a diver at the start of the 70’s oil boom in Aberdeen, these incidents and close calls would play on his mind.

When he would leave his wife Sheila and three kids: Mandy, Jason and Lee for six weeks at a time, Jim said: “I remember when I used to go offshore I would have it in my mind that I might not come back.

“That was every trip.

“I enjoyed the time once I was out there, it was just getting settled back in.”

Harbour engineering jobs included drilling in black water with flooded masks

In his teens and early 20s, Jim spent three years in the Merchant Navy before taking on jobs as a crane operator, motor mechanic and eventually teaming up with his older brother Jacky in his roofing company.

But he was always drawn to water.

“I always had this thing about water,” said Jim.

“I used to love it. My mother said she caught me one time in the pram hanging out the harness trying to touch the silver mudguards because I thought it was water and I was trying to get to it.

“I was always like that. If we went on a picnic, if there was a bit of water, I’d be in there.”

Watching a diver when working one day, he decided to give it a go and he and his wife Sheila joined the British Sub-Aqua Club and often went out diving on the weekends.

Jim and his brother started getting harbour jobs and working on the old jetty in Aberdeen.

They helped renew steel bolts and repair the sea wall with shuttering and concrete.

This led to another job in Peterhead closing the north harbour entrance which included drilling and blasting the sea bed and building a new road and wave wall.

Working in pitch black water

At the time, they were using ex-navy patched up suits called dry bags which made the job a little trickier. Despite the name, they were rarely dry but offered more protection against the cold and contaminated water than wet suits.

With most of the harbours having gates at the time, the water would be pitch black to work in.

Before going in, Jim said you would make a plan but by the time they were 30ft under, the jobs were done by touch in the freezing cold.

Then the shoddy masks would add to the troubles: “Some of the masks I used then were really horrible.

“You’d have a level of water inside your mask and you’re trying to empty it out and drill as well.”

Reservoir job was the last straw

When Jim was offered a job as a civil engineering diver with Comex, a company whose much newer equipment he had always admired, he jumped at the chance.

During the next three years, Jim helped deepen Dover Harbour, construct John o’Groat’s harbour, extend a boat slip in Wick and update New Deer freshwater reservoir with a new wheelhouse control.

However, the dangers of the last job were the final straw.

The first part of the reservoir contract was for Jim to locate the old outlet while holding a sandbag to try and protect him from being sucked through the hole.

With no standby diver and 10 to 15ft of water trying to push him into the opening, Jim said: “When I was finished with that I said ‘That’s it I’m going offshore rather than doing this here for a pittance’.

“Going offshore couldn’t have been more dangerous than that job.

“And another thing, we never had any gloves. We used to have what we called hot water plunges so when you got so cold your hands didn’t work you used to come up to the surface and put them in a hot bucket.

“I was telling the guys offshore about that, it was crazy.”

Jim’s first bell run nearly resulted in disaster

The next 15 years spent offshore certainly were not without their dangers.

In those days, a diver would have a variety of cables in the form of an umbilical cord attached to their suit.

This included the breathing gas for shallow dives or Heliox for deeper dives, a hot water supply, a pnuemo hose (which showed the dive control your depth and acted as an emergency breathing supply), a rope attached to the safety harness, communication cable, a camera and light.

A diving apparatus called a diving bell is used to transport divers from the surface to the depths needed for different jobs.

It helps monitor and maintain the needed pressure for deeper dives.

On one of Jim’s first saturation dives on a two-man bell run, on the Viking Piper in the Ninian Central field, one of the bell-weight wire ropes somehow got entangled with the bell umbilical.

On the way back to the surface, it led to an umbilical cord being pulled out. Thanks to Rocky Stone, the bellman’s quick thinking he quickly closed all relevant skin valves inside the bell keeping the gas pressure steady and them alive.

However, the crew on the surface thought they had lost them.

Once they sorted out the issue, the diving bell was brought back up and the team were “chuffed to see them still breathing”.

The superintendent came on the comms and said: ‘How are you doing Jim?’

Jim shouted back: “I’m thinking civil engineering is looking a lot better now.”

Working on the Tanio oil spill in 1980

In 1980, Jim was pulled in to help with a job just off the coast of Brittany, France after the Tanio, a Madagascan oil tanker, split in half during rough weather.

Jim said: “The back half had stayed floating and the front part with all the oil with it was in the seabed about 90m down.”

This was only two years after the Amoco Cadiz disaster which released 220,000 tonnes of crude oil into the sea in the same area.

Two diving crews, French and British on two dive vessels, The Stephaniturm and the Star Canopus, worked for around six months to pump the oil from the Tanio at the bottom of the sea at around 300ft into a waiting tanker.

The divers spent three weeks in saturation including three days decompressing and one week working on deck then home for one month.

The divers going down would then spend five days in a decompression chamber to simulate the conditions that they experience underwater so there was less risk of getting decompression sickness.

“There were some serious, almost bad times there,” Jim admitted.

Another incident with a diving bell being lifted upside down nearly left the bellman inside a flooded bell. When the surface crew realised their error, they dropped a cable which turned the bell back the right way up.

Jim added: “I remember after we decompressed and went to shore with this guy, the bellman and he was over the moon.

“After a couple of pints, he was running down the road going ‘Thank you! Thank you!’ because he was able to be here.”

10-hour dive ended with a seabed cuddle

At 150m, the usual shift in the water for two divers would be around six hours.

However, on one occasion Jim and his friend John Anderson were left for 10 hours with a faulty helmet.

Due to a helicopter crew change, the crane was not allowed to lift the jib and the pair had to wait it out until the crew change could take place.

Jim said: “The reclaim system wasnae quite working properly.

“So you’d be breathing out and your hat would try and float off and take your head off.

“When you breathed in, it would clamp down on top of you.

“Every time you’d breathe you’d hear the mechanism and it was like it was in your throat and chest. It was nae good.”

Jim decided he’d had enough and indicated to John he was returning to the bell to check out his hat but John decided to have a cuddle instead.

Jim said later he thought John was scared he’d be left on his own waiting for the chopper to leave.

Thankfully the cuddle did the job and after the pair waited it out, they returned to the bell and surfaced.

Charity work in Kosovo led to dangerous situations and guns in faces

After 15 years in the job, Comex lost their contract and Jim decided to “call it a day” after tiring of the weeks away from family and the growing expectations placed on the divers.

He moved into construction and also worked as a steeplejack. However, things changed when he went to try and rescue his daughter Mandy Sangbarani who had started attending a church in Sheddocksley.

Branding it a “cult”, when Jim attended a service he was surprised to find himself lying on the floor after having an experience with the Holy Spirit.

His wife Sheila “dug her heels in a lot more” but eventually the couple became Christians and ended up doing missionary work in Kosova shortly after the war in 1999.

Over the next three years, they helped build over 100 emergency shelters and a 1,000 houses in the Skenderaj area and worked to support those who were most vulnerable.

It was not without its own risks.

“Sheila had a gun to her face,” Jim said. “She told the guy where to go.

“A guy was trying to force her to build a house for a certain group. The guy came into town later and apologised for trying to shoot her.

“It happened to me as well.”

The couple eventually retired and settled in Woodside. However, last July Jim lost Sheila after her cancer came back seven years later.

With teary eyes, Jim quietly said: “Sheila was great. We always looked after each other.”

‘You don’t realise until later on as a grown-up how dangerous the job is’

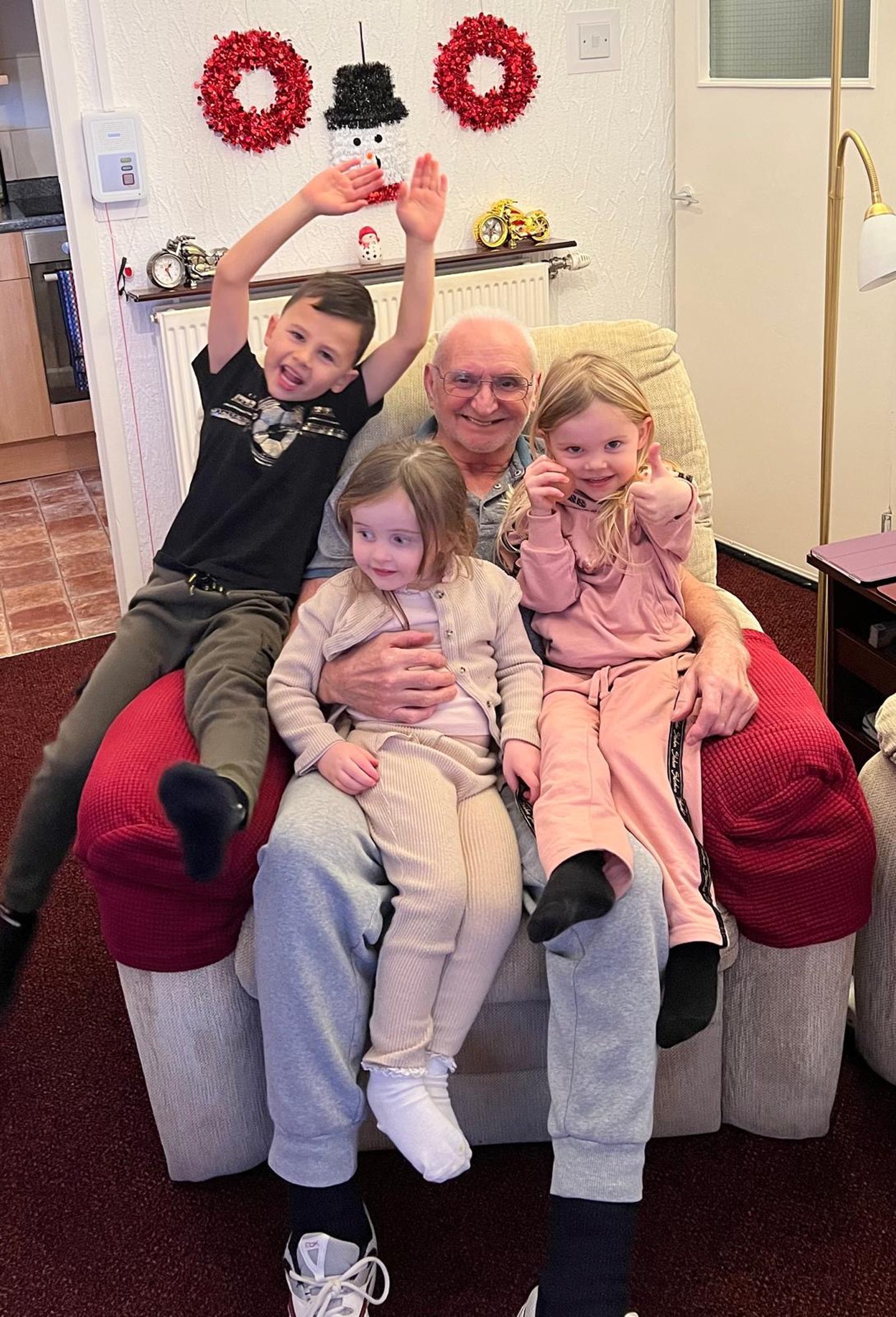

These days, Jim spends time with his five grandchildren, five great-grandchildren and meets with friends and former divers John Anderson and Brian Arnott.

Upon hearing some of their stories, Jim’s daughter Mandy said: “When you’re a kid you just took it for granted dad was away month on month off.

“You don’t realise until later on as a grown-up how dangerous the job is. You hear stories and you’re like wow that’s crazy. Not everybody does that kind of job.”

Conversation