In a bungalow in Tillydrone lives one of Aberdeen’s last connections to a global icon.

Norah Berry, 82, is the granddaughter of Alexander Campbell, one of the north-east stonemasons who helped build Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Her father Sandy went too, at the age of six, to Granite Town, the specially-constructed settlement about 200 miles outside Sydney where the masons carved the huge blocks that made the bridge’s distinctive stone pylons.

Norah, who was born in Fittie at Aberdeen beach, has never seen the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

But her family’s connection to it means it looms large in her life. Her Tillydrone home is full of historical accounts of the bridge’s construction and the Scots community in Granite Town.

But while Norah loves to talk about the stonemasons and the life they led in the Australian outback — which included Scottish dancing and even dressing up as film stars of the day — it’s a part of history not widely known about in the north-east.

That’s mainly due to the passage of time — Norah’s grandfather left Aberdeen for Australia in May 1926 and Sydney Harbour Bridge opened in March 1932.

“How many of these folk are actually left now?” asks Bill Glennie, a local historian who has extensively researched Granite Town and ‘The Quarry Scotties’ who lived and worked there.

Norah ‘represents all of them’ from Aberdeen who helped build Sydney Harbour Bridge

Bill believes the last person to have lived in the town died five years ago, and only descendants like Norah are left to remember the stories.

Granite Town itself was shut down after the bridge was completed and only the remnants of one building remain.

But Bill, a former history teacher from Dinnet in Deeside, says we should be proud of those intrepid stonemasons who were taken halfway across the world because of their skills in cutting granite.

The men and their families were all from the narrow strip of the Don valley stretching from Inverurie into Aberdeen.

As Bill sees it, Norah “represents all of them”.

What was it like to live in Granite Town?

Norah’s recollections mainly come through her father, who in the manner of the time, had the unwieldy full name of Alexander Alexander Campbell. (Her grandfather’s full name was, believe it or not, Alexander Alexander Alexander Campbell.)

The six-year-old Sandy is pictured in a remarkable photograph Norah has of nine of the stonemasons and their families, as they prepared to leave Aberdeen railway station for Liverpool, where they caught the SS Pakeha steamer to Sydney.

Sandy stands holding tightly onto his father’s hand, peeking out from a sea of smart suits and formal hats.

Once in Granite Town, he was enrolled in school — Norah says he was the only one in his class — and quickly made friends with the other stonemasons’ children.

The family lived on Campbell Street, named after them because they were the first to live there.

Making a life in Granite Town

Norah’s grandfather (who everyone called Alex) was in charge of the entertainment at Granite Town and Norah has a picture of him dressed up as Charlie Chaplin.

Bill Glennie even found Alex’s name among a list of quarry workers performing in concerts as the comic duo Flick and Mick.

However, the idea of him as a performer still seems strange to Norah who remembers her granddad as a stern man who didn’t talk much.

She recalls a Christmas dinner in Aberdeen when she was a young girl. She pushed her chair out and accidentally broke the amber handle of her grandparents’ sideboard.

“Oh, it was a row and a half,” Norah laughs. “My mother walked us straight home.”

Norah’s memories of her grandfather in Aberdeen

When the Campbells returned to Aberdeen in 1932 they had one extra member of the family.

Martha, known as Mattie, was born in Australia in 1928 but lived the rest of her life in Scotland and was very close with Norah until her death in 2017.

Bill Glennie believes Mattie was the last surviving resident of Granite Town.

Norah’s grandfather Alex was only 30 when he left for Australia, so when he was eventually returned to Aberdeen he continued working as a stonemason.

He and wife Annie lived on West North Street in Aberdeen in a house that backed onto his granite works.

Norah, who lived nearby, remembers him coming home every night through the back lane and across the washing green.

Norah, meanwhile, was born in November 1941 and went to school at Linksfield Primary and high school at Frederick Street.

As a child, she caught tuberculosis from contaminated milk and was forced to have a hip replacement. Over her lifetime, she’s had seven replacements – six in her right hip and one in her left.

Norah’s husband Charlie died last year, but she is surrounded by family. Her two sons live in the north-east and share their mother’s interest in their Sydney Harbour Bridge connection.

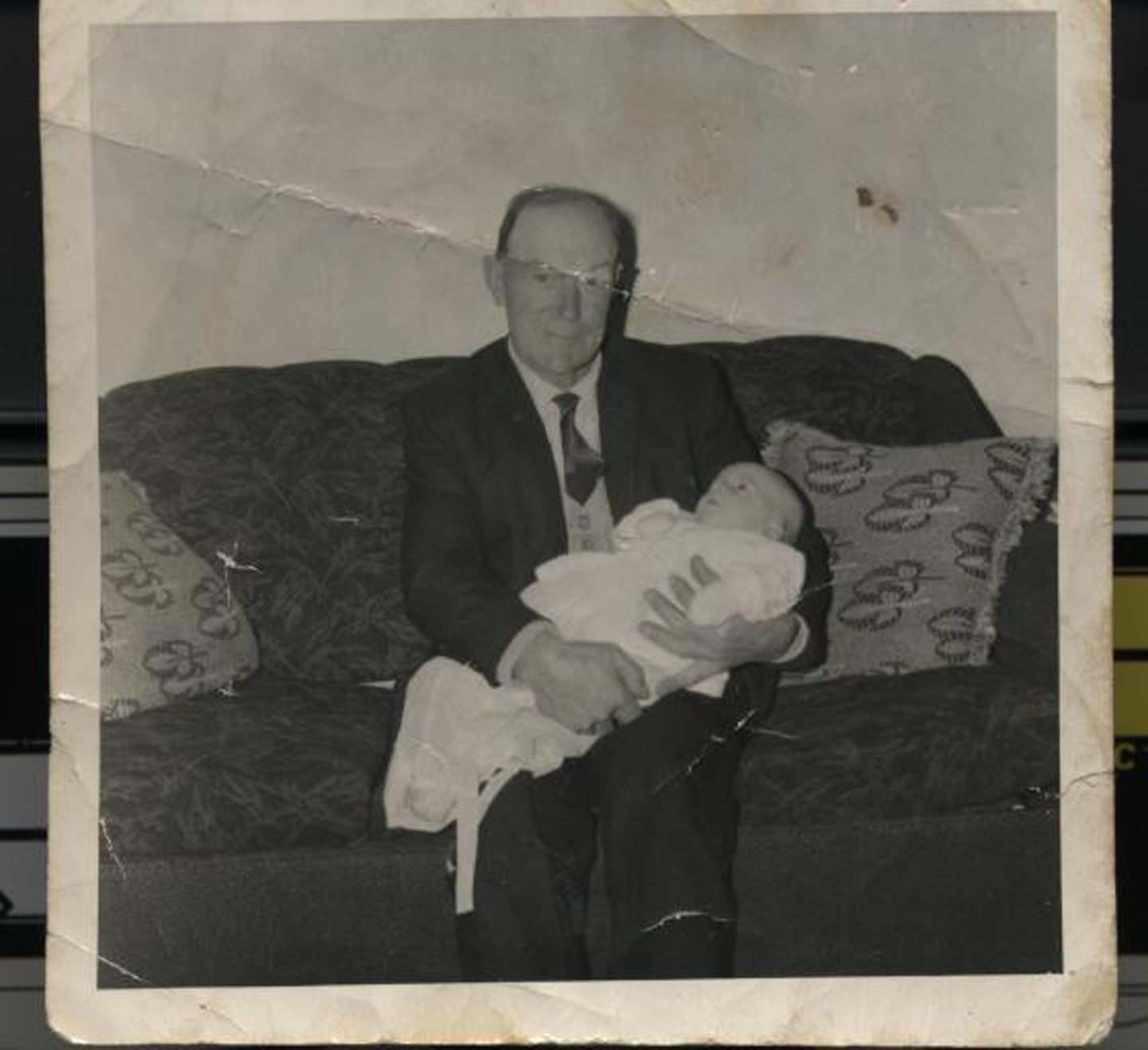

A prized family photo is Norah’s eldest son, Chris, being held by his great-grandfather shortly before Alex died in the late 1960s.

Why the family has yet to return to Australia

Norah would love to visit Australia to see the bridge her family help build but can’t afford today’s air ticket prices.

“I haven’t taken after my mother,” Norah says with a smile. “My mother could make a ha’penny do the work of a shilling.”

Her grandfather and father never returned to Australia, something that Bill Glennie says was common for the stonemasons.

And because Granite Town was so far from Sydney, the only time most workers saw the bridge was when they were getting the boat back home.

But what about Norah’s dad, who always spoke about Australia in glowing terms? Would he have liked to have gone back?

“I think he would have gone back in a blink of an eye,” Norah says.

Conversation