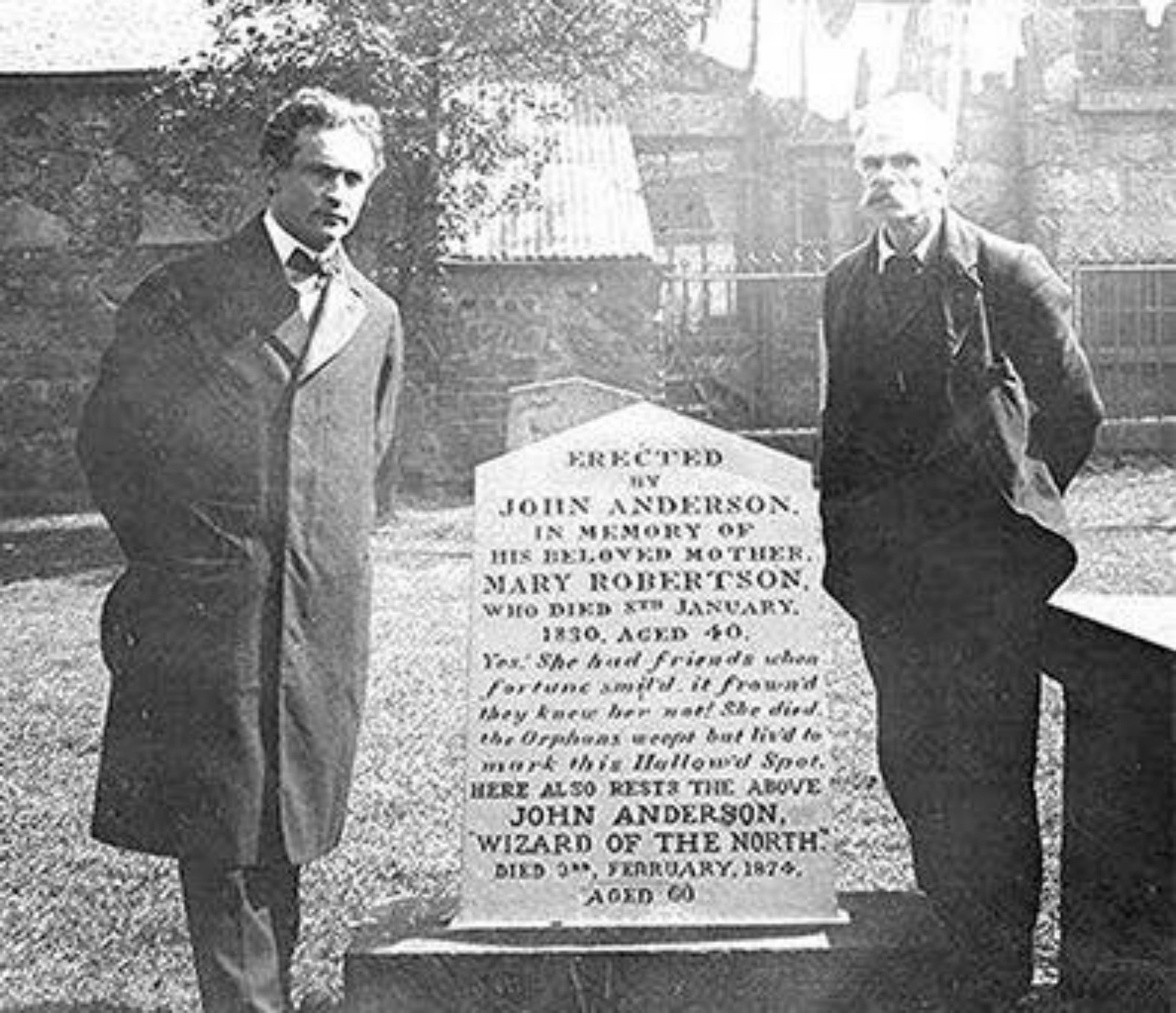

The grave of Aberdeenshire born magician John Henry Anderson, who delighted 19th century audiences with his showmanship, can still be seen in St. Nicholas Kirk yard.

But would it still be there if it weren’t for master illusionist Harry Houdini? Who so admired The Great Wizard of The North that he paid to have the grave maintained.

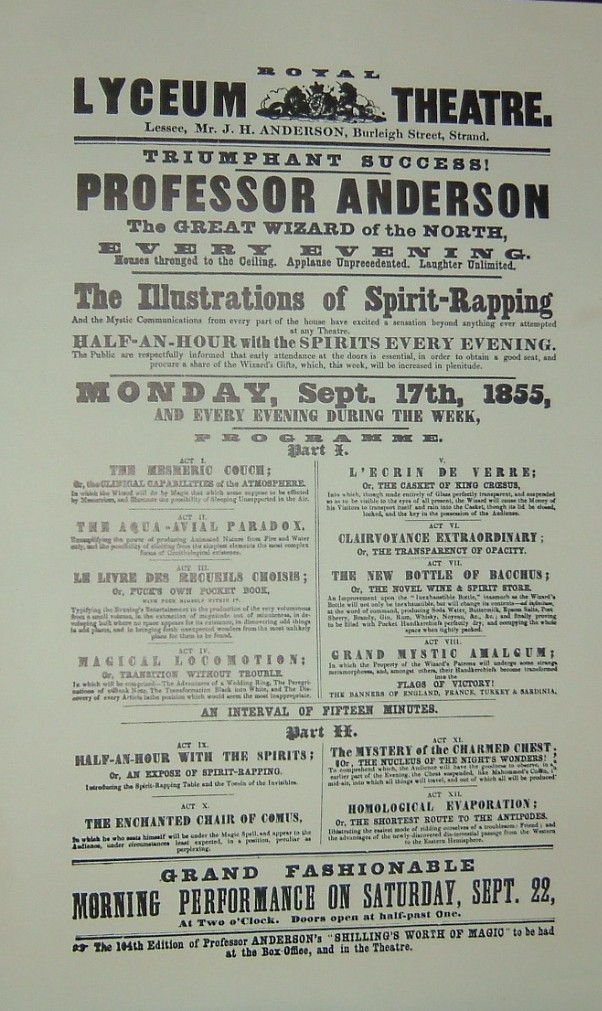

Houdini was the most famous entertainer of his day and was hailed as the greatest magician come escape artist who ever walked the earth.

But his greatest inspiration was none other than Aberdeenshire man, John Henry Anderson. The wizard of the North.

Houdini was born in the same year Anderson died, and in 1909 while doing a run of shows in Aberdeen, the escape artist arranged for the upkeep of the gravesite, which had fallen into disrepair.

While in the city Houdini gave an impromptu heart stopping performance to advertise his up coming shows in Aberdeen.

In characteristic daredevil style the Hungarian entertainer was chained and handcuffed, and thrown into the sea in Aberdeen Harbour in front of thousands of people who gathered to see the unbelievable escape attempt.

Aberdeen police were ready to stop him from the attempt which the officers surely would have assumed meant death under the crushing cold water.

A fierce, blood chilling storm made Houdini’s stunt even more dramatic.

The spectators watched in horror as time passed.

Houdini’s chances of survival were very small.

He resurfaced unscathed.

Houdini’s stage appearances at Palace Theatre in the city’s Bridge Place after the underwater escape were jam packed.

The Aberdeen Free Press (that’s the P in P&J) covered his show on June 29 1909.

The paper’s report said Houdini appeared on stage after films of his “manacled dives” warmed up the audience.

“Then the tit-bit of the evening came. The curtain rose revealing a number of zinc tanks and pails, standing within a tarpaulin and guarded by three attendants, and in a brief space Houdini appeared. He had a great welcome” the report said.

It added: “Short of stature but strongly built, even an evening dress suit failing to conceal evidence of broad, powerful shoulders, he addressed the audience in firm, distinct tones, outlining his programme for the evening.

“The first turn consisted of getting out of a regulation straight jacket, rather a formidable looking garment. Two muscular looking men, who were announced to have lengthy experience in prison work, were commissioned to carry out the “fastening up” process.

But “better was yet to follow” after shrewd local men were invited on stage to examine a large zinc tank, which was filled with water.

The report continues in a tone of obvious admiration and suspended disbelief: “Houdini gave an exhibition of his remarkable powers by remaining in the tin immersed in water for a minute-and-a-half.

“Then, the dislodged water having been replaced, Houdini again entered the tin, a heavy lid was placed on and fixed down with four locks.

“A large screen surrounded the whole, and after about a minute, Houdini drew aside the curtains having emerged from his prison without disturbing the locks.

“The audience simply yelled at the performance, which showed that Houdini’s fame was worthily merited.”

Harry Houdini, was the entertainment phenomenon of his era.

He escaped from chains, locks, ropes and sacks.

They strapped him in and hung him upside down from high building and he somehow freed himself.

They locked him in a packing case and sank him in Liverpool docks and minutes later he surfaced smiling.

Houdini would usually allow his equipment to be examined by the audience.

The chains, locks and packing cases all seemed on the level and it was generally accepted by superstitious Victorians that he possessed superhuman powers.

However, there was something physically remarkable about Houdini admired for his bravery, dexterity and fitness. His nerve was so cool that he could relax when buried six feet underground till they came to dig him up.

His fingers were so strong that he could. undo a strap or manipulate keys through the canvas of a mail bag.

He made a comprehensive study of locks and was able to conceal tools about his person in a way that fooled even the doctors who examined him.

As an entertainer, he combined all this strength and ingenuity with a lot of trickery.

His stage escapes took place behind a curtain with an orchestra playing to disguise any banging, rattling and sawing.

All Houdini’s feats can easily be explained but he belonged to that band of mythical supermen who, we are led to believe, were capable of miracles.

In Edinburgh one of the many other Scottish cities he visited, he was said to have been struck by the number of waifs walking around barefoot in chilly weather.

A long-time benefactor to orphans, he announced a special show for the Scottish youngstersand doled out 300 pairs of boots and insisted that the members of his stage troupe all helping with the fittings.

This wasn’t nearly enough footwear for the gathering mob of children on hand so Houdini trotted the rest en masse to the nearest cobbler shop and had more shoes made to order.

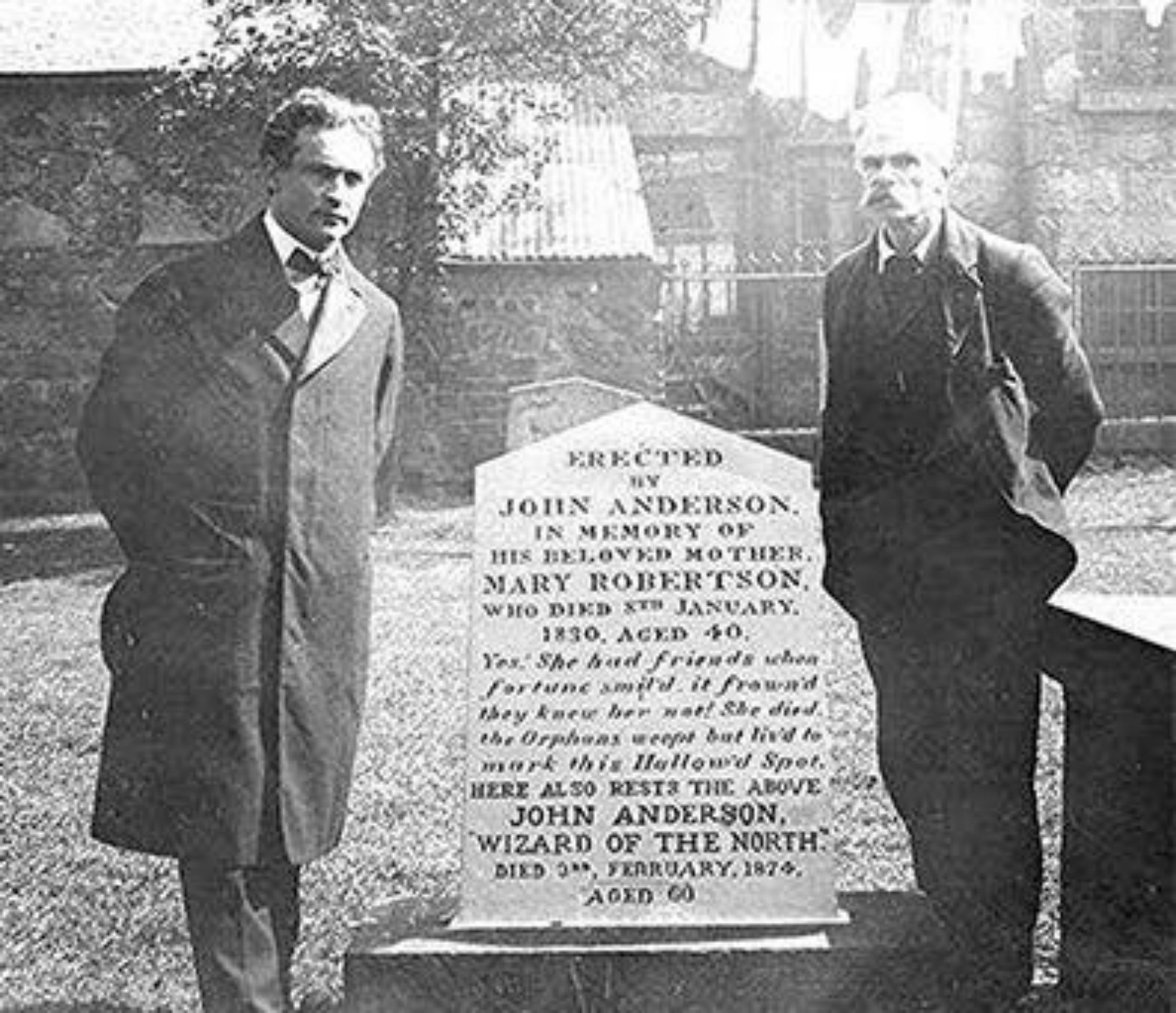

Houdini’s Aberdeen native hero Anderson is credited with helping bring the art of magic from street performances into theatres and presenting magic performances to entertain and delight the audience.

It is believed he even invented the old ‘rabbit out of a hat’ classic.

Orphaned at the age of ten, Anderson started his career appearing on the stage with a traveling dramatic company in 1830. At seventeen, he began performing magic and in 1837, at the age of twenty-three, he performed at the castle of Lord Panmure, whose endorsement of Anderson inspired him to put a touring show together which lasted for three years.

In 1840, Anderson settled in London, opening the New Strand Theatre.

Anderson’s success came from his extensive use of advertising and popular shows which captivated his audience.

The Wizard was committed to philanthropy and expert showmanship, making him one of the earliest magicians to attain a high level of world renown.

Anderson declared: “It is the duty of all magicians to give entertainment,” and he was not content to perform an illusion to simply demonstrate that he could accomplish something that the audience could not explain.

If the effect was not received how he wished it, Anderson would remove it from his act.

Anderson is famous for a lifetime of successful performances of the bullet catch illusion.

Although he did not invent the trick, he made it widely popular and several of his rivals copied Anderson’s version in their own shows.

In 1842, Anderson married Hannah Longherst from Aberdeen, an assistant with his show. The following year their son John Henry Jr. was born.

In 1845, Anderson’s mistress Miss Prentice gave birth to Philip Prentice Anderson, but died in childbirth. Anderson, however, supported the child for his entire life.

Anderson would also have two daughters who assisted in their father’s show and later became successful magicians, and a second illegitimate son with a member of his touring troupe.

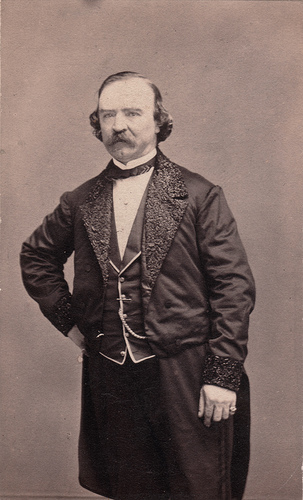

1845 also saw the completion of Anderson’s second theatre, the City Theatre in Glasgow.

In November, only four months after opening, the theatre burned and Anderson’s financial losses were considerable.

Through the aid of his show business friends, Anderson was able to launch a new show at London’s Covent Garden Theatre in 1846 and then toured Europe the following year, travelling to Hamburg, Stockholm, and St. Petersburg, where he met Czar Nicholas I, who arranged a command performance for Anderson after an awkward chance meeting.

In 1849, Anderson returned to London to perform for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

In 1854, John Henry held a farewell performance in Aberdeen. The success of this show was enough to inspire Anderson not to retire. Rather, he began to concentrate his efforts on exposing Spiritualism fraud. In his shows, he used his daughters to duplicate spiritualist effects. Anderson was one of the magicians of his day who exposed the frauds of the Davenport Brothers. The show played at the Lyceum in London and then moved to Covent Garden in 1855. The following year, after a gala performance, the theatre caught fire, destroying all of Anderson’s properties and bankrupting him for the second time in his professional career.

Anderson died in 1874. He was buried next to his mother in Aberdeen.