The fight to save the Doric language has almost become mainstream, as organisations recognise the importance of the mother tongue across the north-east.

And yet Doric is so much more than pronunciation and spelling. It runs beyond forgotten words which trip off the tongue of the older generation; for Doric is a culture, a heritage and a way of life. It was days of hard toil in the fields, the stories told and retold until the fragments became muddled – and the heart stood to be lost.

Not on Dr Don Carney’s watch – or as some may know him, Dr Doric.

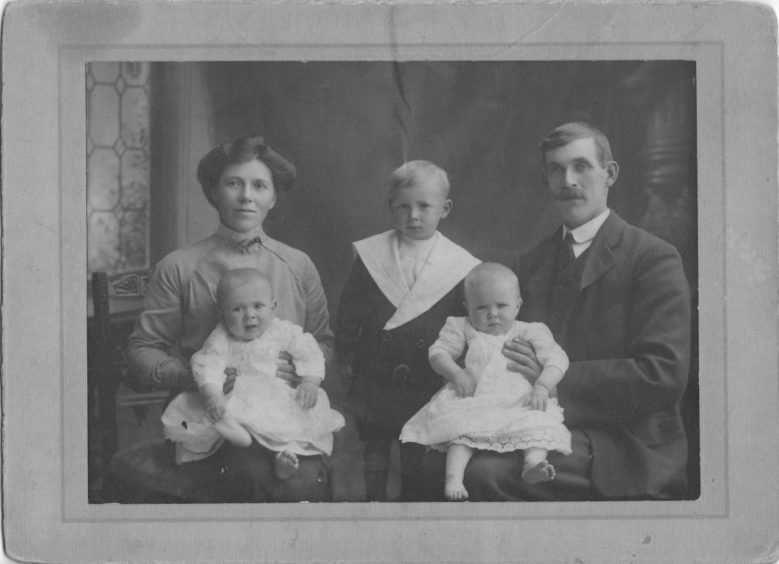

The retired RGU lecturer has spent more than 30 years painstakingly researching the past of his ancestors, having grown up on a farm near Kintore in Aberdeenshire.

Drumnaheath has been farmed by the Carney family for more than 250 years, meaning Don has been able to trace his forefathers for several generations.

But when he started on his quest, Don was astounded to discover that limited data was on offer to depict the shire as it once was, with barely any information recorded in Doric.

It was not grand tales of lairds which Don wished to unearth, but rather the comings and goings of ordinary people.

He believes the ordinary is a universal tale, from the woman washing sheets in the River Nile, to the wifie scrubbing shirts in a sleepy north-east village.

It is the trials, tribulations and traditions which Don has discovered – and he now hopes to preserve his findings for future generations.

His research has seen Don create a remarkable archive, complete with more than 500 hours worth of footage.

His work has now been awarded The Best Scottish Heritage Media Archive, and the title was bestowed earlier this year.

While recognition is all well and good, it is the preservation for future generations which Don is most passionate about.

“I live in Westhill now, but it was life on the farm which sparked my interest all those years ago,” said Don, who holds a PhD in cultural identity of the north-east of Scotland.

“It was hearing my father and grandfather talk about the past, I was fascinated.”

Indeed, stories have driven Don forward, and he went on to interview more than 6,000 people in the north-east.

“It’s the stories that your granny will tell you, only you’ve never thought to ask,” said Don.

“I felt that my ancestors’ contribution had been forgotten.

“I decided that I would like to research, document and concentrate on my ancestors, who lived and worked in rural Aberdeenshire.

“This was driven by pride in who my ancestors were, and what they had done to provide me with the rural environment that I inherited.

“I decided to go round all my neighbours, whose ancestors had also been there for hundreds of years, and speak to them about how things were when they were young.

“I also consulted my own parents, and referred to my mother’s meticulously completed daily diary of life and work, in and around Drumnaheath Farm.

“I was absolutely blown away by the response, and the answers I got from these fine old people about their lives and my heritage. Nobody had ever asked them or shown any interest before about their background.”

Although Don unearthed hundreds of stories, he was particularly struck by a tale from harvest time.

“The oldest or youngest person in the field would cut the last sheaf of the standing crop,” he said.

“The last sheaf was said to contain the spirit of the harvest maiden of fertility.

“It hung pride of place in the house above the oatmeal storage cabinet until the new year, when it was ceremoniously made into three small sheaves.

“One sheaf was given to a cow in calf, and one was given to a horse in foal.

“The third sheaf would be ground into oatmeal and made into four oatcakes.

“When it was time for the first furrow of the year, the farmer’s wife would bring the oatcakes out to the fields.

“One was given to the horseman, the other two were given to the Clydesdales, and the very last bit would be crumbled and ploughed back into the ground.

“This is what I am passionate about preserving.”

Don is a regular speaker and entertainer for events surrounding Doric culture, and also visits social care settings in a bid to use Doric as a means of reminiscence.

“These unique and fascinating stories need to be told as part of our heritage, our status and for educational purposes,” said Don.

“I want to pass this enrichment on to others, so any support in saving this archive as a national asset would be appreciated.

“People need to celebrate who they are, through their past, present and future.”