It’s a phrase which denotes an element of incredulity or astonishment.

And that was the widespread reaction from large sections of the American public to a stream of sensational, salacious stories in newspapers owned by Gordon Bennett Snr and Jnr throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

The men at the helm of the mass circulation New York Herald were trailblazers in the industry even if their critics regularly traduced them as purveyors of kiss-and-tell kitsch, who would resort to any lengths to gain the upper hand.

Newmill

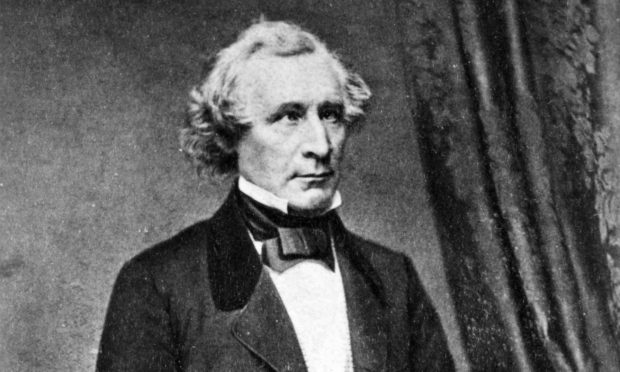

Yet, the majority of people will probably be unaware of how James Gordon Bennett, who was born in 1792, grew up in a strict religious environment in Newmill in Banffshire and initially harboured ambitions of joining the priesthood as a teenager.

Indeed, he entered the Roman Catholic seminary in Aberdeen at the age of 15 and devoted the next four years of his life to religious studies in the Granite City.

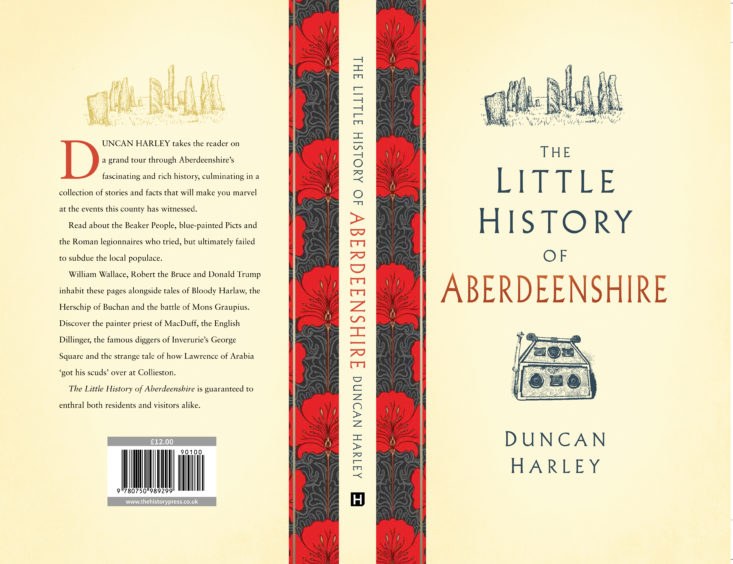

However, as north-east author Duncan Harley discovered, while working on his latest book, Bennett Snr wasn’t just a controversial character who created a massive family dynasty of the sort featured in Orson Welles’ cinematic masterpiece Citizen Kane, but a polarising figure whose son organised one of the most famous meetings in global history – between David Livingstone and Henry Stanley.

In 1819, the 27-year-old Scot joined a friend who was sailing to North America and, after landing in Halifax in Nova Scotia, Bennett briefly worked as a schoolmaster until he had amassed enough money to sail south to Maine, where he again taught at a school in the village of Addison, as the prelude to moving to Massachusetts at the start of 1820.

So far, so respectable.

Yet, following periods as a proof-reader and bookseller which led to him joining the Charleston Courier in South Carolina to translate Spanish language reports, he moved to New York in 1823, embarked on a new career as a freelance writer and was swiftly promoted to the role of assistant editor of the New York Courier and Enquirer, one of the oldest newspapers in the city.

Thereafter, he became increasingly frustrated with the often prosaic, downright tedious nature of much of the coverage in these old journals – and decided that he could and would do better even if it meant shocking readers, defying convention, and occasionally straying into fake news long before the term had even been coined.

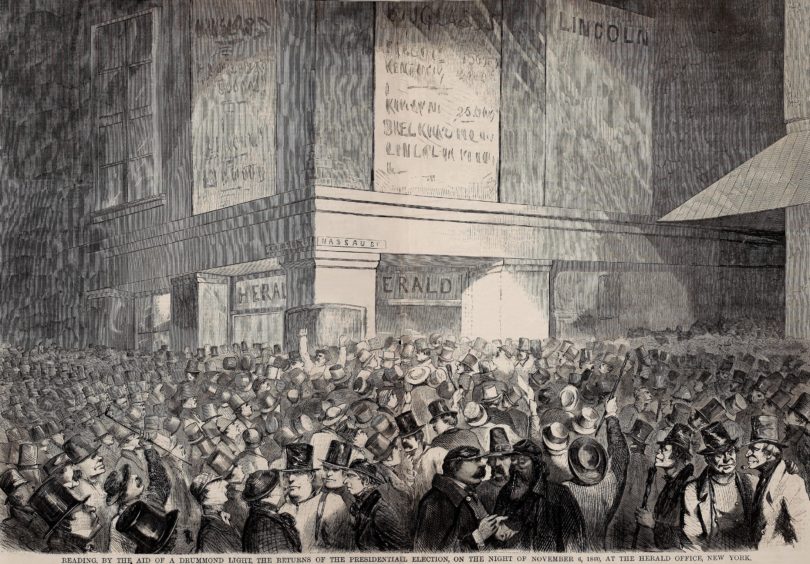

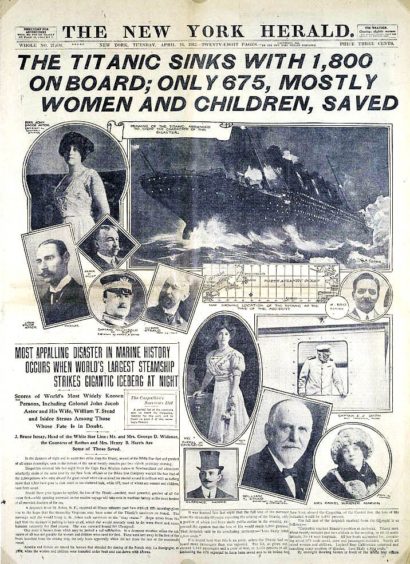

In 1835, Bennett launched the New York Herald and almost immediately changed the landscape. Within its first year, it shocked and captivated readers with extensive front-page coverage of the grisly murder of a prostitute Helen Jewett.

It was a dreadful crime, but Bennett secured exclusive details and subsequently conducted a newspaper interview about it. He was also at the forefront of using the latest technology to gather news and added pictorial illustrations produced from woodcuts.

In 1839, he was granted the first-ever interview with a sitting President of the United States, the eighth occupant, Martin Van Buren and his rapid business ascent continued to raise his profile and the eyebrows of his enemies at one and the same time.

He was part of a new journalistic tradition and Mr Harley, who has previously covered north-east life and lore in his books, The A-Z of Curious Aberdeenshire and The Little History of Aberdeenshire, said he had mixed feelings about some of the methods employed by the far-travelled Scot, whose policies would often have shocked the priests back in his homeland.

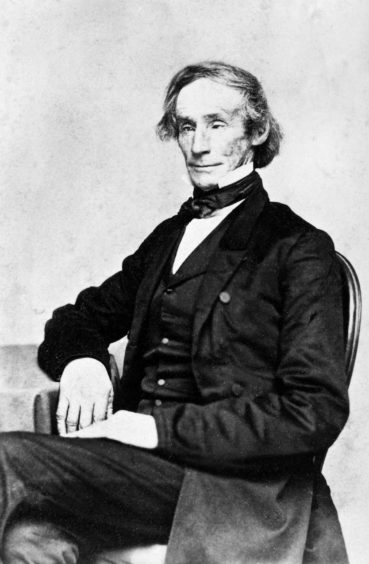

By the time that Bennett passed control of the New York Herald over to his son James Gordon Bennett Jr in 1866, it had the highest circulation of any newspaper in the United States, which ensured its founder was graced with lavish obituaries when he died in 1872.

Thereafter, his son soon faced spiralling threats from Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune and, in future decades, from Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and Henry Jarvis Raymond’s New York Times.

However, while the paper‘s appeal slowly declined under the increasingly stiff competition and changing technologies in the late 19th century and after Bennett Jnr’s death in 1912, it was merged a decade later with its former rival, the New York Tribune in 1924, becoming the New York Herald Tribune for another 42 years.

Amalgamation

That amalgamation was greeted with considerable success and reputation in its last half-a-century until it finally closed in 1966.

Bennett Snr endowed New York City Fire Department’s highest honour for bravery in 1869 after his home was saved from destruction by the courageous response of firefighters.

It remained one of the department’s highest honours for 150 years, but in recent times, there have been concerns voiced about the Bennetts and the Herald’s tendency to use racist language and prejudiced attitudes when covering stories such as the abolition of slavery.

One commentator described him as “a gifted and controversial editor, who transformed the American newspaper”.

He said: “Expanding traditional coverage, the Herald provided sports reports, a society page, and advice to the lovelorn, which soon became permanent features of most metropolitan dailies.

“Bennett covered murders and sex scandals in delicious detail, faking material when necessary, but his adroit use of telegraph, pony express, and even offshore ships to intercept European dispatches set high standards for rapid news gathering.

“Combining opportunism and reform, Bennett exposed fraud on Wall Street, attacked the Bank of the United States, and generally joined the Jacksonian assault on privilege.

“But, although defending labour unions in principle, he assailed much union activity. And because he was unable to condemn slavery outright, he opposed abolitionism.”

Those perspectives make it difficult for modern commentators to see eye-to-eye with Bennett on many issues.

He had similar problems with the vision thing.

After all, he was cross-eyed for most of his life and an acquaintance once remarked: “When he looked at me with one eye, he looked out at the City Hall with the other”.

His legacy lives on: there is a street named after him from West 181st Street to Hillside Avenue in the Washington Heights neighbourhood of northern Manhattan, and a New York City amenity, Bennett Park, was created in his memory along Fort Washington Avenue.

There is also the Avenue Gordon Bennett in Paris, next to Stade de Roland Garros, the venue for the annual French Open tennis tournament, which is currently taking place in France.

It’s a remarkable tale, whatever one thinks of the fashion in which Bennett conducted his affairs. He had a grand ambition and brought it to fruition – which delighted him and his family, including his wife and three children.

Kiss and tell

But he infuriated rivals and fostered resentment and downright loathing in other people in the business. His methods also divided the public, but he simply pointed to the circulation figures as proof that he had struck on a winning formula.

As Mr Harley said: “James Gordon Bennett Snr’s name is often used as a convenient euphemism for expressions of surprise along the lines of ‘Cor blimey’ and ‘Would you believe it’.

“Born in 1792 at Enzie, his family later moved to Newmill just outside Keith. He worked for a while in a local haberdashery on Mid Street before moving first to Aberdeen, then to North America where he drifted into the newspaper business.

“In 1835, he set up the New York Herald and began publishing amongst other things ‘kiss and tell’ stories. It seems that, in 1836, he offered a reward to any woman who was prepared to ‘set a trap for a Presbyterian parson and catch one of them in flagrante delicto.’

“He was described by a rival press baron as an ‘obscene foreign vagabond, a pestilential scoundrel, an ass, a rogue, a habitual liar, a loathsome and leprous slanderer and a libeller’.

“Yet, although he was obviously a colourful character, he was also a shrewd newspaperman who sent out fast boats to meet the European ships before they made landfall in order to be first with the transatlantic news.

“His son carried on the running of the family newspaper empire and despite his flamboyant and eccentric behaviour which often scandalised the high society of his day, he continued to pursue sensational news stories.

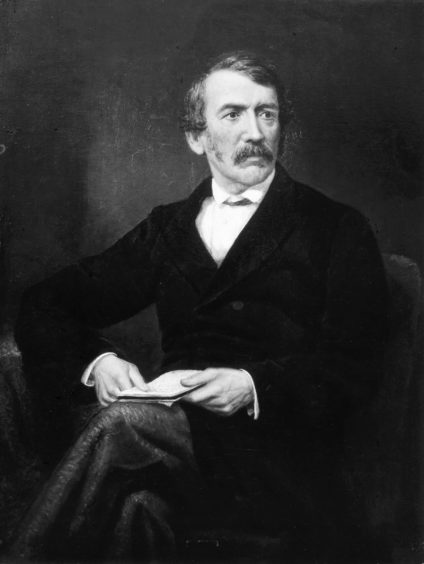

“In 1869 for example, he funded Henry Morton Stanley’s successful expedition into deepest Africa in order to locate the Blantyre-born missionary David Livingstone.

“Stanley’s mission was successful giving the Herald an exclusive account of Livingston’s various achievements (and the utterance of the words preserved for posterity ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’).

“Perhaps Bennett Jnr’s most bizarre claim to fame is his odd connection with Asteroid 305 Gordonia.

Discovered in 1891 by French astronomer Auguste Honoré Charlois, the heavenly body was named in honour of Gordon in recognition of his patronage of the Camille Flammarion Observatory outside Paris.

“His headlines were sensational and perhaps suffered from glaring inaccuracies, but he lent his name both to a figure of speech and an interstellar piece of rock which was last seen travelling around the universe at some 30km a second.”

The father figure was the type of redoubtable granite man who marched out into the world and didn’t give a hoot about upsetting anyone else on his journey.

But Gordon Bennett, this dynamic duo didn’t half change the history of newspapers in the process.

Mr Harley is currently working on a new book called Northern Lights.