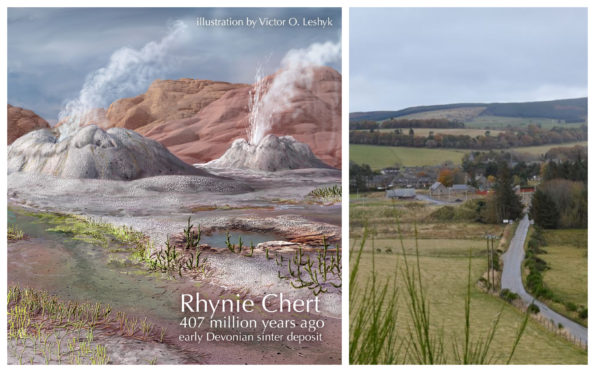

With violent geysers, bubbling hotsprings and unrecognisable creepy crawlies and plantlife, the Aberdeenshire landscape looked a lot different 407 million years ago.

But new research on fascinating fossils discovered near the village of Rhynie has helped scientists to bring the prehistoric world of ancient Scotland back to life as part of work conducted by French scientist Christine Strullu-Derrien.

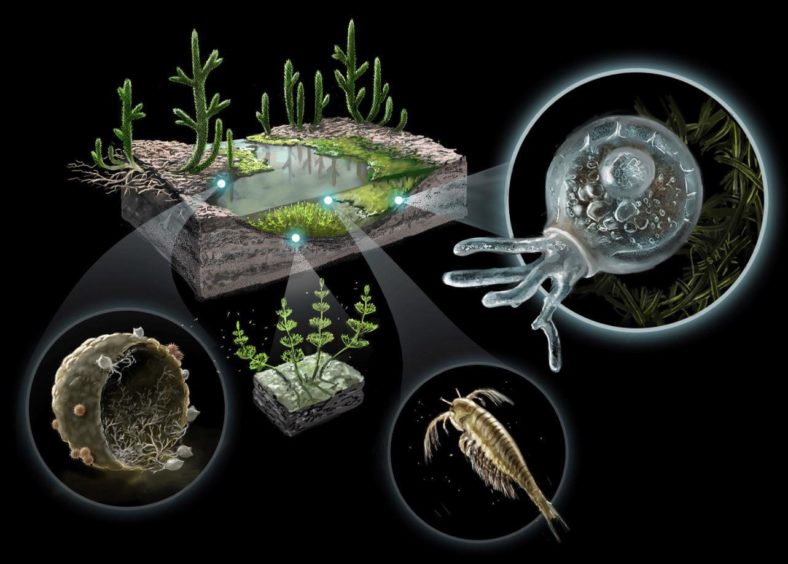

Ms Strullu-Derrien works in the field of paleomycology – the study of fossil fungi – and has been recently analysing samples of the Rhynie Chert, a deposit that has almost perfectly preserved some of the very earliest examples of life’s colonisation of land.

The fossil area, first discovered by medical practitioner William Mackie in 1912, is so important to humanity’s understanding of the first terrestrial life that Ms Strullu-Derrien says Rhynie should be considered a “world heritage site”.

Her recent academic work has been vividly brought to life by paleo-artist Victor Leshyk, from Arizona, who has illustrated what Rhynie would have looked like 407 million years ago when the Rhynie Chert was formed, as well as the life that lived there.

Ms Strullu Derrien, who also works with the National History Museum in London, said: “The Rhynie Chert is so important because it beautifully preserved all of the ecosystems, including the animals, plants, fungi, bacteria – everything is preserved in-situ.

“So we can use it to explain how ecosytems worked at that time, and it really is a unique place in the world for this age of 407 million years ago.

“It should be a world heritage site, because it really is the only one of its kind.

“We really should be shouting about how important it is to science.

“It helps us to understand what life was like at the beginning of the colonisation of land by plants.

“The landscape was very similar to what we have in Yellowstone today, a hot spring environment with a climate that was far more warm than we have now.”

Ms Strullu-Derrien said her current work is on the relationships between plants and fungi, and the Rhynie samples are helping her to understand the origins of this relationship.

She added: “You cannot write the story of the evolution of this relationship only with molecular data, you need the fossils too, which we have with the Rhynie Chert.

“A lot of people have worked on the chert, but there is still a lot more work to do and a lot more to discover.”