In Alison Anders’ flat on Claremont Street in Aberdeen, Detective Constable Hamish Moir was meticulously scanning the environment around him.

He had already spotted ashes in a fireplace, which provided cast-iron proof that Anders was involved in an audacious attempt to steal £23 million from her Rubislaw-based firm, Britoil.

And then – DC Moir eyed something else.

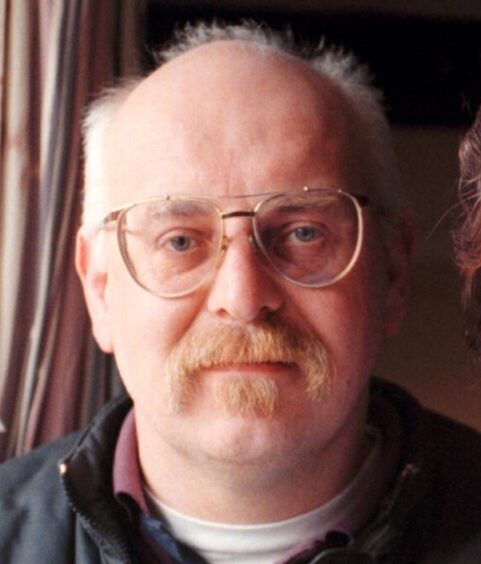

A notebook, with all the pages blank.

On closer inspection, he noticed something else.

Something unusual.

An untrained mind would have missed it, but DC Moir’s eagle eye was about to blow the case wide open.

He noticed there were faint indentations in the notebook – the kind of marks made by a pen writing something on the previous page.

Never one to leave a stone unturned, DC Moir sent the notebook away for analysis.

The now-retired detective told us: “We gave it to the Identification Bureau and it takes a while for the results to come back.”

When the findings landed in Aberdeen CID’s in-tray, detectives got their next big breakthrough.

“The indentation said ‘Holiday Inn’ and had a number next to it,” said DC Moir.

Halfway across the world

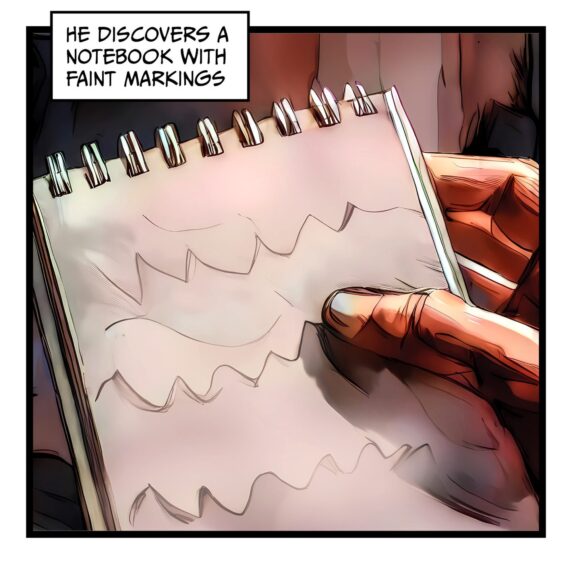

It was logical for police to assume that the number denoted a particular Holiday Inn hotel.

But figuring out which one was much trickier back in 1988.

This was, of course before you could simply Google a search term and have your answer immediately.

So detectives had to think smart.

DC Moir said: “I went out to the Holiday Inn at Dyce because the head of security there was someone I knew – a guy called Jimmy Ritchie who was a retired DCI.

“I said ‘have you got a directory telling me what this number relates to?’ and he nodded.”

Mr Ritchie went away into a supply room and came back with a thick book, flicking the pages until finally, he found it.

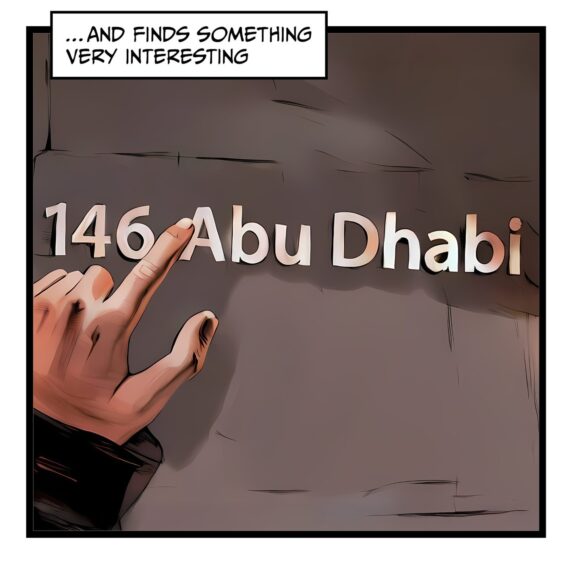

“It’s the Holiday Inn in Abu Dhabi’.”

‘We knew Alison was there’

DC Moir said: “Immediately – we knew that’s where Alison would be.

“We later learned Anders had fled to Glasgow Airport and panicked before the afternoon flight to Amsterdam and so flew to Paris and on to Abu Dhabi.”

Police were stunned for two reasons.

First, people in the late 1980s didn’t just pack up and go to the Middle East regularly.

It was reserved for people who worked in the oil industry or who were rich enough to afford exotic holidays, not 29-year-old cashiers on low salaries.

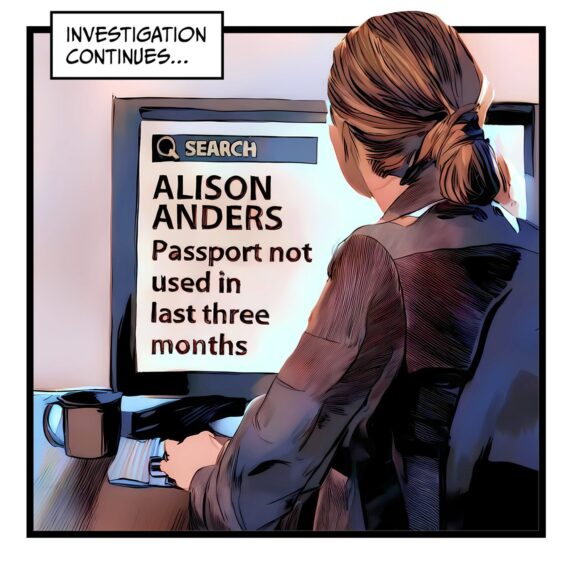

Second, police had been keeping tabs on Anders’ passport – and it had not been used.

Baffled, detectives pieced together what they knew in the hope it might help their investigation.

How could she have left the country?

DC Moir said: “We knew she had gone, she hadn’t got the fraud money, and she’s in Abu Dhabi – so, what’s the connection?”

At this stage, it’s worth saying that, though police saw this case as a top priority, they knew time wasn’t a factor as it would be with other crimes.

If a murderer is on the run, time is of the essence – but it’s not the same with fraudsters.

And if the case is under wraps, there isn’t the same level of public pressure to make arrests as there would be if it were all over the papers.

It took a week for the story to leak out of Britoil and on to the front pages of the Evening Express, though senior staff did their best to keep it in-house.

News of this massive attempted embezzlement was all over the north-east, but it didn’t draw out any new information for police.

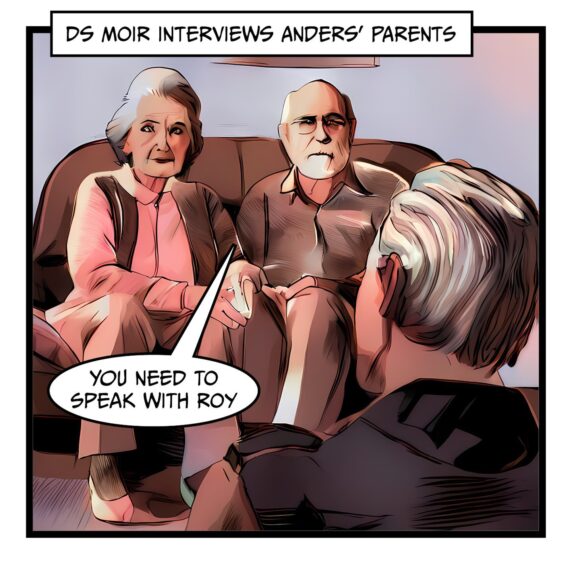

The next logical step for Grampian Police was to speak with Anders’ parents, James and Elsie, who lived in a leafy part of Kent, in southern England.

Initially, detectives told them they were concerned for their daughter’s welfare.

But the couple saw through that.

“They knew there was more to it, with detectives flying down,” said DC Moir.

He added: “They were a genuinely nice couple.

“Eventually, we told them what their daughter had done.”

‘You need to speak to Roy’

And then a new name entered the frame.

Mr Anders, a retired adult education principal, told the officers sitting across from him in his living room that there was another person they might want to quiz.

“She had a bridge partner named Roy Allen – and they’re maybe more than just bridge players,” Mr Anders told the police.

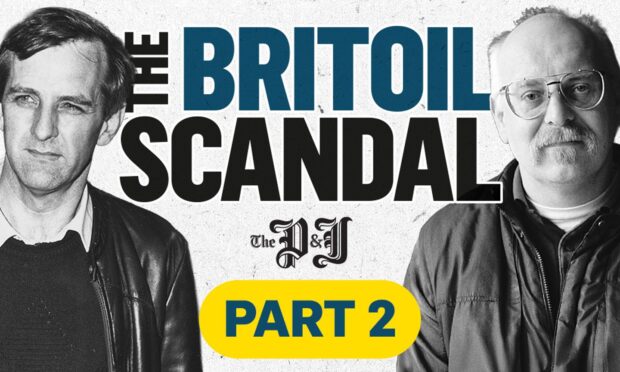

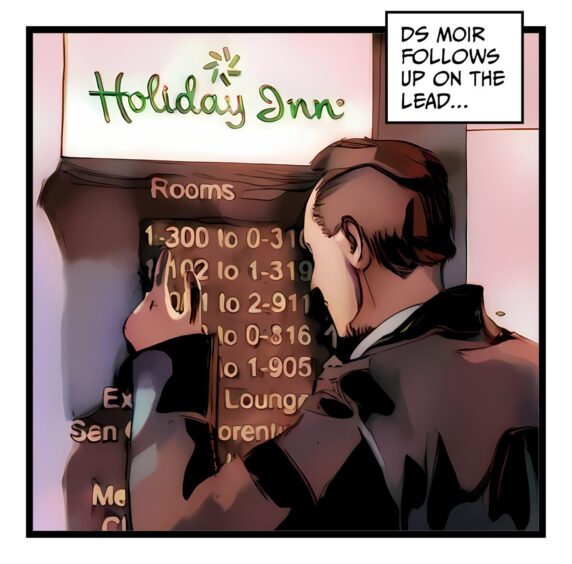

That was the first time detectives had heard the name of Royston Darrell Allen, who was then 35.

An athletic, outgoing ladies’ man, five years older than Anders, Allen was popular around Aberdeen.

He helped start the Granite City Oilers American Football team and was highly respected in the oil industry.

Born in England, Allen had moved to Aberdeen in 1984 to become a partner in Atom UK, which did work for a number of firms, including Britoil.

An office affair

That meant he would often call in to the Britoil offices, passing Anders’ desk.

She found him funny and charismatic, and liked that he shared her love of bridge.

There were feelings of mutual attraction, with one major problem.

Allen was married with two children.

That didn’t put the pair off, though – and Allen would exploit a quirk of ambiguity to help him cheat on his wife, Megan, with Anders.

Because Roy would say he was going “to Al’s house” – and Megan assumed ‘Al’ was a man, rather than Alison.

After speaking with Anders’ parents, police were keen to talk to Allen, but he was working offshore, so they awaited his return.

Abu Dhabi the common link

In the meantime, detectives dug into Allen’s business dealings – and found an interesting fact.

DC Moir said: “He was working in Abu Dhabi.

“He is there, we suspect Alison has gone there – that’s the connection.”

Upon his arrival, Allen was remarkably keen to speak with police, going to Queen Street straight from the airport.

DC Moir said: “Roy openly admitted that his regular bridge games with Alison were less about the bridge and more about the apres-bridge at Alison’s flat.

“He was worried because his wife didn’t know.

‘We both thought his involvement was 50/50’

“Roy would have known he was in the firing line, but we didn’t push him hard.

“I remember saying to (Det Sgt) Peter Willox when Allen left ‘What do you think – is Roy connected to all of this?’

“We both said ‘I don’t know – it’s probably 50/50’.

“Roy came across as a guy you could go for a pint with, a nice guy.

“Roy claimed to know nothing about the crime.

“We had to put that aspect of the inquiry on hold for the time being.”

With no evidence of Roy’s involvement, police could not arrest him.

And there was still no sign of Anders using her passport.

All detectives could do was instruct Interpol to put Anders on a red notice – so she would be arrested when her passport was used – and hope.

DC Moir said: “Everything kind of went cold with the investigation.

Piper Alpha became the focus

“In terms of priority, the fraudsters hadn’t got the money, there was no repeated offending, and it was white-collar crime.

“This wasn’t a ‘serial killer on the loose’ situation.”

Another factor was that the Britoil fraud took place a week before one of the worst disasters in the region’s history.

On July 6, 1988, the Piper Alpha oil platform exploded 120 miles off the coast of Aberdeen. The tragedy resulted in the deaths of 167 people.

It was a tragedy that stunned the region, overwhelming hospitals and inundated CID.

DC Moir said: “At that time, Piper Alpha had happened.

“So there was a huge amount, maybe 75% of the guys on CID were put on to that investigation.

“There were limited resources to deal with other crimes, so low priorities were put to the side.”

As winter arrived, investigators had no new leads, so they used a tried-and-tested method that was very much of its time.

While today, police appeal on Facebook, the 1980s boasted a highly effective equivalent.

DC Moir said: “We went to Crimewatch.”

Watched at one stage by a quarter of Brits, this monthly BBC show profiled notorious criminals and appealed for information.

The often sinister-looking mugshots and ominous reconstructions led to presenter Nick Ross ending each show with the catchphrase: “Don’t have nightmares, do sleep well”.

‘We want to see this woman’

As the episode was screened, officers would man phones in the London studio, eager for people to crack their cases.

The episode lasted 45 minutes, and the Britoil segment lasted 30 seconds.

It was so short because of Crown Office restrictions.

Prosecutors, of course, want a conviction.

But they also don’t want to give too much information away during the investigation that could prejudice a jury or help a criminal go free later.

DC Moir said: “The Crimewatch mention was organised by DCI Harry Milne through contacts at the BBC.

“We went on to say, ‘We want to see this woman’.

The show was massively popular at the time and, had she been in the country, somebody would have seen her,” DC Moir.

“I was in the studio in London and we had two guys sitting in the major incident unit at Queen Street in Aberdeen.”

While the matter at hand was deadly serious, DC Moir recalled being concerned about the BBC’s level of hospitality.

He said: “In the green room, there is a bar and food.

“You do a rehearsal, then go back and there’s more drink and you’re thinking ‘don’t drink too much because you have to answer these phones – and you can’t leave the studio to go to the toilet’.”

Alison Anders’ face was screened to the nation, but the response was modest.

‘It confirmed to us – she had gone’

DC Moir said: “We got four calls from people saying things like ‘I saw her at a chip shop in such a place’ – total nonsense.

“What it confirmed to us was that she wasn’t in the UK.

“The show was massively popular at the time and, had she been in the country, somebody would have seen her.

“We deduced she must be overseas and must have got there somewhere that wouldn’t show up on the system.”

While Anders was overseas, Roy Allen was still in the UK.

And things were not good in his personal life in the spring of 1989, almost a year after the £23m Britoil fraud attempt.

Allen’s wife, Megan, found out about his affair with Anders and left him.

DC Moir said: “One day I came into the office and my colleague said ‘Megan Allen and David Nance are here for you – they are now in a relationship’.”

David Nance was Roy Allen’s business partner.

Allen had found out that Mr Nance was seeing his estranged wife, Megan.

In comments disputed by Megan and Mr Nance, DC Moir said: “There had been fighting and arguing.

“David was staying in a caravan at Hazlehead, and Roy had gone up and threatened to kill him.

“(Megan and David) came in to see us because they were scared. They wanted Roy locked up.”

‘Something isn’t right here’

Though it has been disputed, DC Moir claimed it was this alleged personal disagreement between Megan and David and Roy that led to a massive breakthrough in the Britoil fraud case.

DC Moir told us: “Megan and David said ‘we think Roy was involved with Alison in this fraud’.

“They said ‘over the year since the £23m Britoil fraud, Roy has received phone calls in the office from a woman who has given her name as Ann Killick’.

“Megan had taken one of the calls and recognised Alison’s voice and thought ‘something isn’t right here’.

“They suspected the woman using the name Ann Killick was Alison Anders.”

Detectives were confused by this new information – but elated.

“I was thinking ‘yes, here we go – this is opening things up. Let’s go from here’,” said DC Moir.

Today, Dr David Nance and Megan are married. They are directors in Balmedie-based Keir Developments Ltd.

In a statement, Dr Nance categorically denied DC Moir’s version of events.

Dr Nance said: “At no time did Roy Allen threaten to kill or in any way harm Megan or myself, and the police contacted us first regarding the attempted fraud.

“At this point, we were both unaware of Roy’s involvement.”

Beyond that, the couple have chosen not to comment for this series.

There is no suggestion that either of them played any role in the Britoil fraud or had any knowledge of it before it became public.

Mystery woman calls Royston Allen

However it came about, though, Grampian Police had their breakthrough.

Here was an allegation that Roy Allen had been receiving secret phone calls from a mystery woman named Ann Killick – and that woman might just be the fugitive Alison Anders.

These phone calls were received at Roy Allen’s office, and so detectives got a warrant to search it.

That would lead to a spectacular development.

- The P&J made several attempts to contact Alison over a period of several months and she did not return our messages.

COMING TOMORROW IN PART THREE: How mastermind fraudster Alison Anders impersonated a dead schoolgirl to go on the run in a plot twist taken straight from the pages of The Day of the Jackal.