More than 25 tonnes of plastic and other rubbish has been removed from north-east beaches over a two-year period by thousands of volunteers giving up their free time to clean Scotland’s seas.

From August 2018 to September last year, the Turning the Plastic Tide project carried out 67 beach clean-up events with people of all ages along the coastline from Fraserburgh to East Haven in Angus.

The scheme, part of the East Grampian Coastal Partnership group, has engaged with 2,500 volunteers, who gave 6,000 hours of effort to take humanity’s harmful waste out of the marine environment.

And although 30 events had to be cancelled following the announcement of national lockdown in March 2020, the project’s coordinators have continued their work despite the pandemic.

As well as great deal of work engaging with school children, the organisation launched its Take Four For The Shore initiative, which challenged visitors enjoying Scotland’s coastlines to pick up at least four bits of litter in a Covid-compliant manner.

Among the 25.36 tonnes of rubbish hauled off the north-east’s shores was a one-tonne mass of ghost netting – old nets that float loosely in the sea, causing harm to the environment.

The netting was among the 4.38 tonnes of marine litter removed from Sandford Bay at Boddam in May 2019 in just three hours with the aid of Aberdeenshire Council’s landscape services.

Decades of pollution

Crawford Paris, project manager of Turning the Plastic Tide, explained the enormous quantities of debris removed shows the importance of sustainability, recycling, and disposing of waste responsibly.

He highlighted a number of finds that washed up or emerged from the sands following recent storms.

One example was a crisp packet from around 1968 discovered at Newburgh, highlighting the years of trouble that pollution can cause the marine environment.

Mr Paris said: “What we just experienced in the last week or so of persistent winds has resulted in quite a lot of debris washing in, whether it be ropes and nets, or general litter that you drop in the street and eventually finds itself at sea.

“This crisp packet that was found in Newburgh is made of layers of plastic that are fused together, so sometimes like here you can see the outer layer becoming deteriorated, but it’s still perfectly legible and intact.”

It is believed the crisp packet had been buried in a sand dune.

He continued: “When you’re talking about something that’s 50 years old and you can still read it today, it really puts things in perspective.

“A teenager could drop a crisp packet, and then find it again in relatively the same condition by the time they’re in their 50s, which is really quite mind-blowing and scary.

“Plastic is one of these materials that never disappears, it just fragments and gets smaller and smaller, and the smaller it gets the more species it can impact.

“It can be ingested by animals, and through that become part of ecosystems.”

“It just breaks your heart”

Therese Alampo, nature reserve manager at the St Cyrus National Nature Reserve (NNR), said a number of items dating back decades have been found on the beach after this month’s storms.

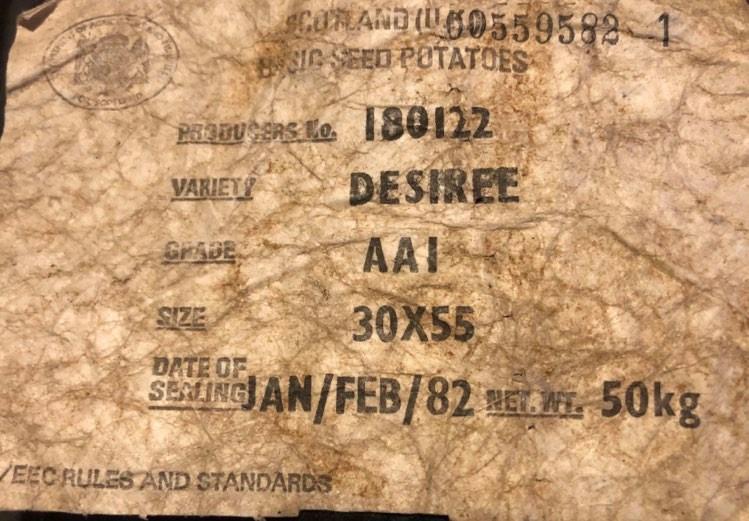

One was a very old-fashioned broken jar of James Keiller and Son’s Dundee Marmalade, now considered a vintage collector’s item. Another was a potato sack dated 1982.

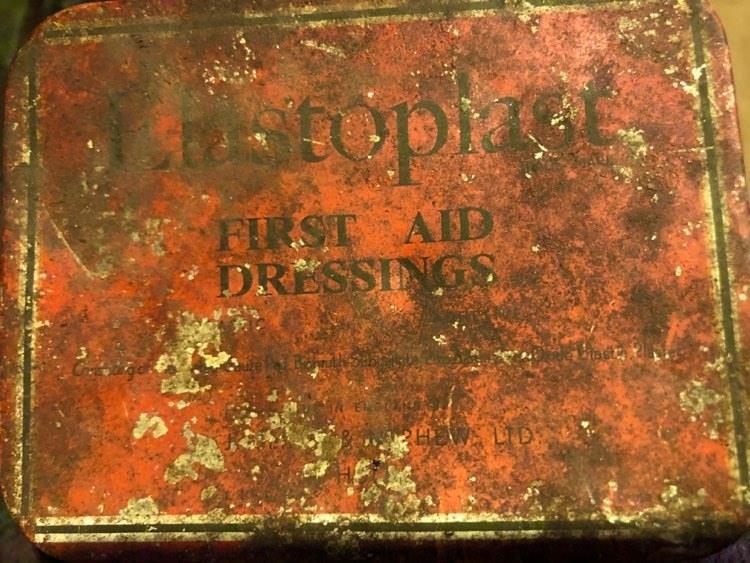

She also highlighted a tin of Elastoplast first aid dressings, which Ms Alampo believes, after some internet sleuthing, could be more than 100 years old.

She said: “The most shocking thing for me was this tattie sack label, it’s made of some sort of plastic and it’s just incredible how long it’s lasted.

“It’s been in the marine environment for who knows how long, but it’s really alarming that it’s lasted this long.

“I wouldn’t want to bet money on how long these items have been in the sea or in the sand, but it just goes to show how persistent our rubbish can be.

“There’s always so much doom and gloom online so I like to post photos of these interesting finds, but the truth is the vast majority of the things we find on the beach is quite depressing.

“It’s bits of rope, nets, plastic, polyester, and these kind of things that just stick around for donkey’s years.

“Volunteers do spend so much effort cleaning up our beaches, and when you finish a day of it and it’s pristine it feels lovely – but then storms come and wash up so, so much plastic and it just breaks your heart.

“It can feel overwhelming, but every bit of plastic picked up is a bit that won’t end up in a seabird’s stomach, or a turtle getting entangled, or even ending up in our fish dinners.”

“Our throwaway society really needs to change”

Lauren Smith, a marine biologist and Scuba diver with the marine research and conservation group Saltwater Life, lives in Newburgh and frequently collects rubbish as she walks the region’s beaches – and even carries out underwater litter-picks while diving.

As well as the crisps from around 1968, this month she also came across a milk bottle she says could date back to 1993.

Ms Smith said: “I believe the bottle and this crisp packet have been locked in dunes, which is why they still have colour on them, because usually as soon as things like get in the water and are exposed to sunlight, they degrade and break down into smaller bits quite quickly.

“Wherever it originates, if it eventually gets into the sea it’s not going to do any good.

“Larger things like old fishing gear can pose serious entanglement threats to larger marine life like dolphins or whales, but then you’ve got these smaller things like crisp packets or plastic bottles, that break down into smaller and smaller bits that can be easily eaten.

“Even the tiniest of microplastics can be found in plankton, and if fish eat them, it can become part of the food chain.

“You can even find plastics in the nests of coastal-nesting birds, it’s really sad to see.

“It’s all very depressing. I’ve done beach cleans for years and years, and sadly it’s still a problem.

“Even when I’m diving, we’ve removed trash that’s actually in the sea – it’s really awful to consider that what we see washed up is only a small part of the real scale of the issue.

“We really need to find a way of changing the system to stop this at the source.

“Our throwaway society really needs to change before we can make a real difference.”

“Only a smaller part of the wider marine litter problem”

Mr Crawford said the threat of today’s litter still posing a threat to generations to come in the decades ahead must be addressed.

He added: “These historic pieces of litter are good at capturing public interest, but they’re only a small part of the wider marine litter problem, which is happening on a much, much larger scale.

“We’re producing plastic products now at a rate we’ve never done before, and if you think about just how much of that ends up in the marine environment today, it’s worrying to think how much will still be floating around out there in 50 or 60 year’s time.

“The problem could really be a much, much bigger problem in decades to come, so it’s an issue that needs to be tackled at its source as soon as possible.”