Three weeks ago I went for a walk in Glen Feshie.

The last time I did that, 18 years ago, Safeway was being bought by Morrisons, Vladimir Putin was President of Russia, and the SARS coronavirus was threatening a global pandemic. Clearly, some things never change, but that certainly can’t be said of Glen Feshie.

This Cairngorms glen, snaking its way south of Kincraig for over 10 miles, is one of the largest ecosystem restoration projects in the UK. Central to its restoration is a management decision to reduce the deer population to densities low enough to allow woodland to grow back of (mostly) its own accord.

It’s a 200-year vision but, even now, just 17 years after it began in earnest, the result is a landscape utterly transformed.

The benefits to biodiversity, carbon sequestration and flood prevention are all well documented but projects like this are not without their critics. Local communities risk being alienated if they have little input into what goes on, and debate rages among supporters as to the preferred methods of ecosystem restoration – to fence or not, to plant or not, to be patient or not?

But, in this instance, I’m less interested in the roads travelled and more interested in how the destination itself makes us feel.

Lush diversity of life in abundance

I knew what to expect beforehand, as Glen Feshie isn’t the only such project in Scotland, but the unrestrained exuberance of the place still came as a surprise after my long absence. I spent much of my visit standing and gawping, all the while muttering delighted expletives to myself. One visit clearly wasn’t going to be enough, so when my next day off came along just two weeks later, I excitedly hurried back.

The big old Scots pines were there in 2003 of course but, even though there were plenty of them back then, there was no younger generation to take their place. Any seedlings or saplings that dared poke their heads up above the grass or heather were nibbled away, so the glen was little more than a beautiful retirement home for venerable old trees.

But now the trunks of those same granny pines are disappearing into a nascent forest. Former open ground, freed from grazing pressures and energised by sunlight, has filled with young pine, birch, juniper, willow and much more besides, all effortlessly reaching for the sky.

Even in its upper reaches, the glen is uncharacteristically lush, its many shades of green lending the landscape an alpine depth and texture completely alien to most hillwalkers in Scotland. Indeed the diversity of life on display is so rampant that it’s difficult to know where to look. Mammals, insects, wildflowers, reptiles, birds, they’re all here in abundance.

On my second visit, when I heard the distinctive sound of claws on bark, I turned my head and expected to see a red squirrel. Instead, I saw a pine marten clinging to a large pine, staring back at me, before bouncing off across the woodland floor.

I’m subconsciously being pulled towards more dynamic places

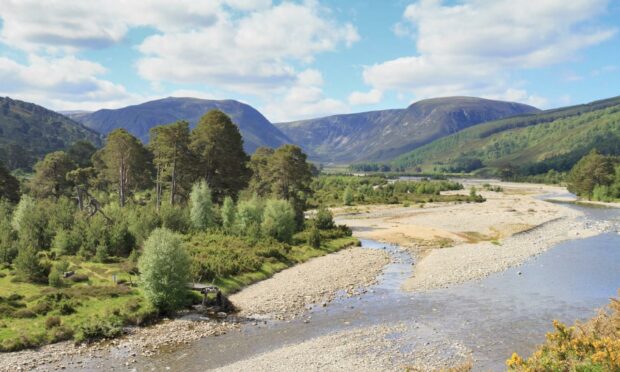

But while the scale of the place is typical of most other Highland glens, this steep-sided one with its heavily braided river, mighty flood damage and increasingly dense vegetation has a rugged grandeur more akin to a wild and remote delta in the Pacific Northwest than a glen in Scotland. It’s therefore familiar but unfamiliar too, hence a strange feeling of dislocation while I was there.

Panoramic pic of upper Glen Feshie yesterday. It barely feels like Scotland tbh. You might need to click on it to see the full pic 🙂 #Cairngorms pic.twitter.com/q3lXqvYbVN

— Ben Dolphin (@CountrysideBen) June 19, 2021

Glen Feshie feels alive and vital in a way that so many other glens in Scotland just don’t, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the more I’m exposed to places like this, the more I find my tastes changing.

Walking through Glen Feshie, the world feels irrepressibly optimistic

I still enjoy immersing myself in the big, open, treeless spaces of Scotland. They’ll always have an almost primeval, humbling appeal, I guess. But increasingly I find that rather than deliberately avoiding treeless glens where little more than the seasons ever change, I’m subconsciously being pulled towards more dynamic places like Glen Feshie, Mar Lodge, or even small, local regenerating woodlands.

Of course, I can’t tell anyone else how they should feel about landscape-scale restoration like this, I can only tell them how it makes me feel. But I can at least recommend that they take a walk through a naturally regenerating landscape like this before they make up their minds about it, because I genuinely can’t recall visiting such a gobsmackingly beautiful and uplifting place.

Walking through Glen Feshie, the world feels irrepressibly optimistic, and optimism is something we could all surely do with right now.

Ben Dolphin is an outdoors enthusiast, countryside ranger and former president of Ramblers Scotland