One afternoon in July 2014, a group of people gathered to dig a hole next to the River Don in Tillydrone.

They weren’t burying a body, they were marking the spot of the UK’s very first urban hydro project – and the timing was crucial.

In four days’ time, planning permission for the whole development would expire. But the hole was dug and everyone cheered. Work – such as it was – had begun.

Now, they just needed to find £1.2 million.

What is a micro-hydro?

The basic principle of hydropower is that water is piped from a higher level to a lower level, with the resulting water pressure being used to generate electricity.

For most people, an image of a huge dam probably springs to mind. But “micro” versions do exactly the same job just on a smaller scale.

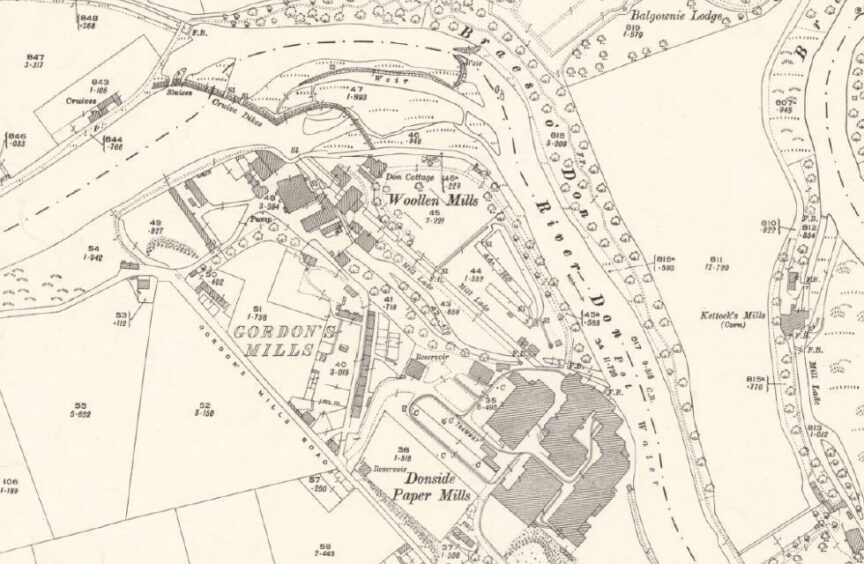

The Tillydrone micro-hydro scheme is located on a bend of the River Don at the edge of a former paper mill.

By short-cutting this bend in the river, the hydro makes use of the sloping river bed that drops about 2.5m and over a distance of just 200m.

The installation uses a 25 tonne Archimedes screw to move the water from the high ground to the lower ground.

It is this flow of water that drives a mechanical shaft which then drives an electric generator.

A cable connects the whole project up to the national grid and the renewable energy flows seamlessly into our homes.

Just a couple of miles from Aberdeen’s city centre, it’s the first urban hydro project of its kind in the UK.

But getting it up and running wasn’t easy.

Why the green dream nearly didn’t happen

For hundreds of years, the River Don powered all kinds of industry. The first paper mill opened in 1696 and was soon joined by wool and cornmeal factories, all fuelled by the unrelenting flow of the water.

But as technology advanced, companies left the riverbanks one by one, leaving nature to take over once more.

The was until 2014 however, when a house builder earmarked a former mill site as the perfect spot for a new housing development.

It was to be an all-new type of development – a mix of houses and flats, private and social housing with community at the heart and powered by three turbines which could harness the power of the Don to light up the streets of the new estate.

Many house-hunters had their imaginations captured by the promise of this idyll and put down deposits on houses.

“I absolutely loved the idea of the renewable energy” said Jane Fullerton, a director of Aberdeen Community Energy. “It really attracted me and my husband when we were looking for a house at the time.”

Sometime later however there were mumblings of financial difficulties from the developers. They had run out of money they said, and so the idea of the turbines was quietly abandoned.

But it seemed that the developers had done something right – they had achieved that sense of community they had set out for, and this community weren’t giving up their green energy dream without a fight.

Quick, someone find a digger!

At a meeting in early 2014, local resident Sinclair Laing first floated the idea of a community-owned hydropower plant on the banks of the Don.

He explained that all the hard work had already been done. Exploratory work and planning permission had all been granted for the original turbine project, and it remained valid for five years.

All it needed was a few volunteers, and £1.2 million, to get it off the ground.

“Once I picked my jaw up off the floor at the price I put my hand straight up,” said Jane. “I knew absolutely nothing about hydropower or turbines but I wanted to be involved.”

As the small group of volunteers did the maths, they realised that four years, 51 weeks and three days had passed since planning permission had been granted.

“We had four days to start the project, so we went to the river and convinced one of the builders nearby to bring down a small digger,” Jane said.

“We dug a big hole and the project had begun.” Aberdeen Community Energy was formed.

Where did the money come from?

Things were stagnant on the building side of things for the next wee while.

“I suppose you could say there were a lot of I’s to be dotted and T’s to be crossed,” Jane laughed.

First up, money.

The project was set to cost £1.2m and in the end was mostly financed by CARES, a Scottish Government renewable energy scheme which gives grants to small-scale energy projects.

But the team still needed to find £500,000 to top up the purse.

“We floated our shares and in 21 days we had raised the cash and were turning people away,” Jane said. “It was incredible.”

By this time, the team had been living through a crash course in hydropower and a new deadline had reared its head: September 28 2016.

It all came down to 24p

To ensure the project would be financially viable, the team decided to use the Westminster feed-in tariff.

This would guarantee a set price would be paid for each kilowatt of energy they produced.

However, to be approved for the tariff various planning permissions and licences must be approved, then submitted to Ofgem who would approve things again and after all was approved for a final time, work could finally begin on site.

Oh, and all that had to happen within two years. This meant after all the paperwork and construction, the team must be producing energy within two years of applying for the scheme – which happened to be on September 28.

“We made it with one week to spare,” said Jane with a laugh. “If we hadn’t, it wouldn’t have been financially viable and all our work would have been for nothing.”

The tariff guarantees a price of 24p per kilowatt hour (kwh). Payment rises in line with the retail price index and is guaranteed for 20 years.

Without it, prices are volatile and hydro producers may receive anything as low as 7p per kwh for their energy.

This fund closed in March 2019, meaning that unless you’re already signed up, no new hydro facilities can benefit from it.

“It means that it’s not really feasible to set up hydro schemes like this at the moment,” said Jane.

“It’s all down to government legislation.”

Cutting through the government red tape

Micro-hydro experts all say the same: battling against bureaucracy is the hardest part.

Run-of-river schemes like the Tillydrone hydro operate on the same basic principles: water is taken out of a river, it’s used to turn a turbine to create electricity, then the water is replaced downriver.

But you need a licence to take the water out and another to put it back and, understandably, levels are strictly controlled to protect fish.

“You also need to pay an extraction fee for removing the water, even though you’re immediately putting it back in,” said Simon Hamlin, CEO of the British Hydro Association.

He explains that wind and solar don’t need to pay for their “fuel” (ie wind or the sun) in this way.

Plus, the cost of solar panels and wind turbines has dropped significantly in recent years, meanwhile the price of concrete – hydros are about 70% concrete – has gone up.

“The whole issue with the government’s energy strategy is that it’s a shambles,” Simon said.

“They are obsessed with renewables but what they actually mean is offshore wind.”

According to Simon there is more than two gigawatts of energy (the equivalent to three million solar panels) not being harnessed from UK rivers each year.

Northern Scotland has the most hydro possibilities of all thanks to the hilly terrain and heavy rain.

And hydro technology lasts more than 100 years with minimal maintenance, so investments are long term.

But start-up costs, extraction licences and other complicated rules are making it difficult for new community set ups like the one in Tillydrone to get off the ground.

And the red tape doesn’t stop once you are producing energy.

“We could be producing about 40% more power than we currently do but our tariff says we are limited to 99kwh because we are a micro-hydro,” Jane said.

“If we produced more our rates would be cut in half so it’s just not worth it.”

Is hydro really our future?

Meanwhile, the gigantic screw is churning away day and night on the River Don.

Recently the project hit its biggest milestone to date; producing two million kwh of energy.

To put that into context, one kwh is enough to watch TV for 12 hours, while two million kwh means that the river is now fully powering approximately 100 homes each year.

“It happened in the wee small hours of October 17,” said Jane. “It’s been a real milestone to reach and we are totally delighted.

“We are producing energy which doesn’t cost the planet anything and doesn’t cost the river anything.

“I like to think it shows what can be done. Fossil fuels are not the be all and end all.”