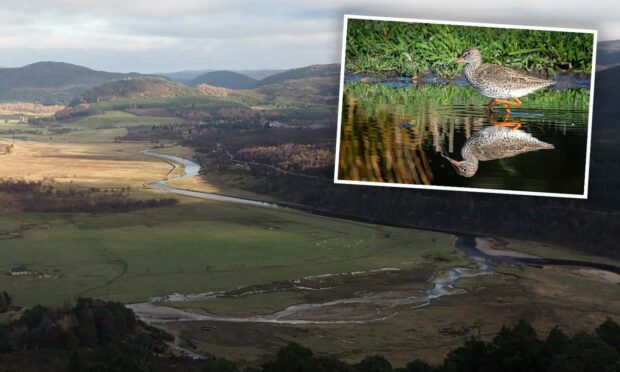

Struggling bird species have found new homes in Deeside created by the devastation of Storm Frank.

The extreme weather event at the end of 2015 caused millions of pounds worth of damage across Scotland.

Roads were washed away, bridges were shut, and towns and villages were completely cut off.

In the Deeside community, the storm caused severe flooding that destroyed homes and businesses.

But now, six years on, many birds which are facing challenges across the country are finding new opportunities in new habitats created by the disaster.

How rising waters carved a new home for threatened species

The immense rainfall during Storm Frank caused many rivers and waterways to burst their banks.

In the floodplain west of Braemar, the storm caused the River Quoich to permanently changed its course.

In the new paths the waters of the Quoich now flow across the grassy floodplain, wader species like redshanks have found ideal habitats.

The wetter environments are good for invertebrates, which keep the birds well fed.

In 2014, prior to Storm Frank’s impact on the area, the number of breeding wading birds on the plain was about 40.

But by 2017, that figure had more than doubled to 82 pairs in total.

This year there have been around 58 pairs recorded, including curlew, common sandpiper, snipe, lapwing, ringed plover, oystercatcher and redshank.

Manmade efforts to help tackle ‘biodiversity crisis’

Shaila Rao is conservation manager at the National Trust for Scotland’s Mar Lodge Estate near Braemar.

She said seeing the waders thrive in the habitats created by Storm Frank, as well as by the estate itself, has been encouraging.

“We’re facing a biodiversity crisis, and wading birds like curlew and lapwings are doing quite badly nationally, so to see them increase is a very positive thing,” she said.

Shaila said the habitats on the floodplain west of Braemar are a “perfect” combination of factors for waders.

But such wet environments are rare in Scotland.

She continued: “Lots of parts of Scotland have been drained historically to improve the ground for grazing or agriculture.

“But waders like it to be wetter, with puddles and ponds.”

In 1996, Shaila said the National Trust worked with Invercauld Estate and the RSPB to “re-wet the floodplain”.

Former drainage ditches were replaced with dams, and following the changes, waders flocked to the area.

Since then, wader numbers in the area have fluctuated year on year due to all sorts of factors, including weather.

But Shaila said ensuring there are suitable homes for breeding pairs on the floodplain will play a key part in their continued presence in the area.

The National Trust has recently been creating new “scrapes” with diggers in the area, shallow ponds with gently sloping edges that hold water for waders.

It has also been clearing rushes from the area because the tall plants can prevent birds from spotting hungry predators.

Protecting humans from impact of climate emergency

But the floodplain is not just for the birds.

By storing water during periods of heavy rainfall, the grassy plains west of Braemar can limit the impact of flooding in communities downstream like Ballater and Aboyne.

Shaila explained that if events as horrific as Storm Frank will become more frequent as a result of climate change, regions like the floodplain in the upper reaches of the Dee will prove crucial.

She said: “This floodplain floods quite regularly now, so from a climate emergency perspective, it’s a really valuable site.

“It really holds back an awful lot of water when you get big flood events, like Storm Frank, it can help to temper the peaks of the waterflow.”