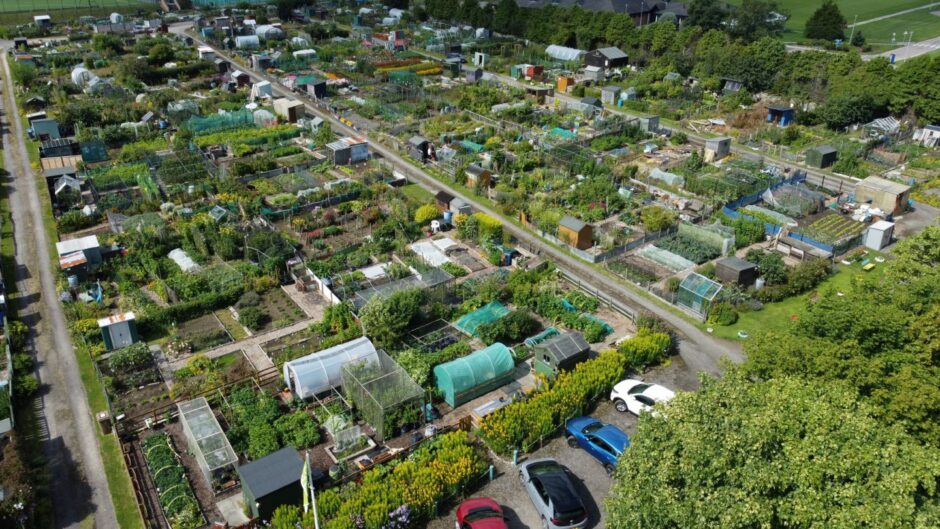

The north and north-east needs more allotments and it needs them in more accessible places, according to one Highlands researcher who believes Scotland could be doing much more to feed itself sustainably.

Corrinne Ferguson, who lives in Nairn, recently completed a degree in sustainable development and for her thesis she investigated the sustainability of micro-scale growing in Scotland.

It inspired her to think differently about the way we use much of our urban green space.

She found that Scotland has the skills, knowledge and space to grow much more of its own food in micro plots like allotments, and with all the political and financial uncertainty in our future, now might be a good time to put that to use.

Allotments aren’t just a hobby, they can be a food lifeline

Today, allotments are seen as a pleasant hobby for green-fingered people with a lot of time on their hands.

“This is not how allotments started out at all,” said Corinne.

“They first came into existence around the First World War when there were concerns that Britain may not have enough food to feed itself.

“With Covid, Brexit, geopolitical uncertainty and the cost of living crisis… we are facing similar questions now, will we be able to feed ourselves?

“We ran out of toilet paper pretty quickly and look at the panic that ensued… what would happen if we ran out of food?”

Around 80% of food we eat in the UK is imported, and Corinne believes this needs to change.

Obviously we can’t grow everything all year round, she says, but we could be doing far more than we currently are.

Allotments, while not the only solution, offer a real opportunity to start this process.

15-year waiting lists need to change

As part of her thesis research, Corinne spent a significant amount of time on allotments around the Highlands, speaking to plot holders.

There were a few key themes which came up time and again:

- The quality of fruit and veg produced. “It sounds obvious but people really do grow stuff and feed their – and other – families with it, and they enjoy it because the quality and taste is excellent.”

- The knowledge. “There is a huge swathe of knowledge within allotments – the plot holders know all the best environmentally sustainable methods and they use them too. They know how to grow stuff here and they know how to grow it well.”

- The case for more allotments across the UK. “Almost everyone seemed to be aware of the long waiting lists to get an allotment.”

“Allotments are significant producers of food, there is no doubt about it,” said Corinne.

“You can be truly self-sufficient throughout the season which actually surprised me.”

The issue is that there just isn’t enough of them.

In 2020, between Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire councils there were over 300 people on their waiting lists for allotments. Today’s waiting list is three years long.

Other councils, such as Highland and Moray do not provide allotments themselves, instead encouraging local allotment associations to provide them.

The waiting list for these can be even longer, with 15-year waits not uncommon.

Should we have public growing places in parks?

Another bugbear Corinne has with current allotment provisions is their location.

Often, they can be in parts of town which are difficult to reach on foot or by public transport.

“And when you do come across these places, they are behind a fence and you have to apply and get on a waiting list before you even get close to it,” she said.

“We need a lot more public growing spaces and we need to make growing your own produce more accessible.”

During the course of her research, she says she was impressed by the approach in parts of Africa, where grassy roadside verges are regularly used to grow food as well as parts of parks and open space in urban areas.

“There is lots of land we can utilise in Scotland for the same purposes,” she said.

I have an allotment in Scotland, could I turn it into a business?

Another barricade which Corinne believes needs to be looked at is the specific rules around selling produce from allotments.

There is much discussion about the legality and ethics of selling allotment-grown produce, and according to Corinne, local authorities can be “quite strict” about making money in this way.

The Allotments Act 1922 has a general prohibition on any “trade or business” being conducted on an allotment. But allotments are allowed to have an allotment shop, which councils tend to regard as fundraising rather than a business.

Some interpret the law to mean that while you cannot trade at the allotment, you can sell surplus produce away from the site. In general, the spirit of the law is that commercial growers shouldn’t use council-operated sites as a low-cost way to operate a business.

Of course if you sell a few courgettes to your neighbours and there’s no need to inform HMRC, but you do need to let it know if it’s more of a business.

An HMRC spokesperson says: “Going to the market every day with a pile of produce to make money means you are trading – you need to let us know and pay tax on profits.”

“I think these laws are out of date,” said Corinne. “Allotments are a very successful way of growing food and feeding ourselves but we need utilise all types of enterprise to really be able to do it.”

Conversation