Just outside of Forres lives an unassuming man who countless ospreys, white-tailed eagles and red kites owe their lives to.

Roy Dennis OBE has worked in the Highlands and islands since 1959, tirelessly fighting to bring back wildlife once driven to the brink of extinction in the UK.

And although he’s now 83, he’s showing no signs of slowing down in his dedication to wildlife in Scotland and beyond.

The leading conservationist is well known for his work restoring the osprey population, and spearheading the reintroduction of red kites.

Throughout his decades-long career, Roy has collected plenty of accolades under his wing.

He was made an MBE in 1992 and later in 2004 received the RSPB Golden Eagle Award after being voted as the person who had done the most for nature conservation in Scotland in the last 100 years.

And now, Roy has been recognised for his incredible efforts once more and was proud to be included in the King’s New Year Honours list.

This is Roy’s remarkable story.

A lifetime working with wildlife started with tadpoles and humble beginnings in Hampshire

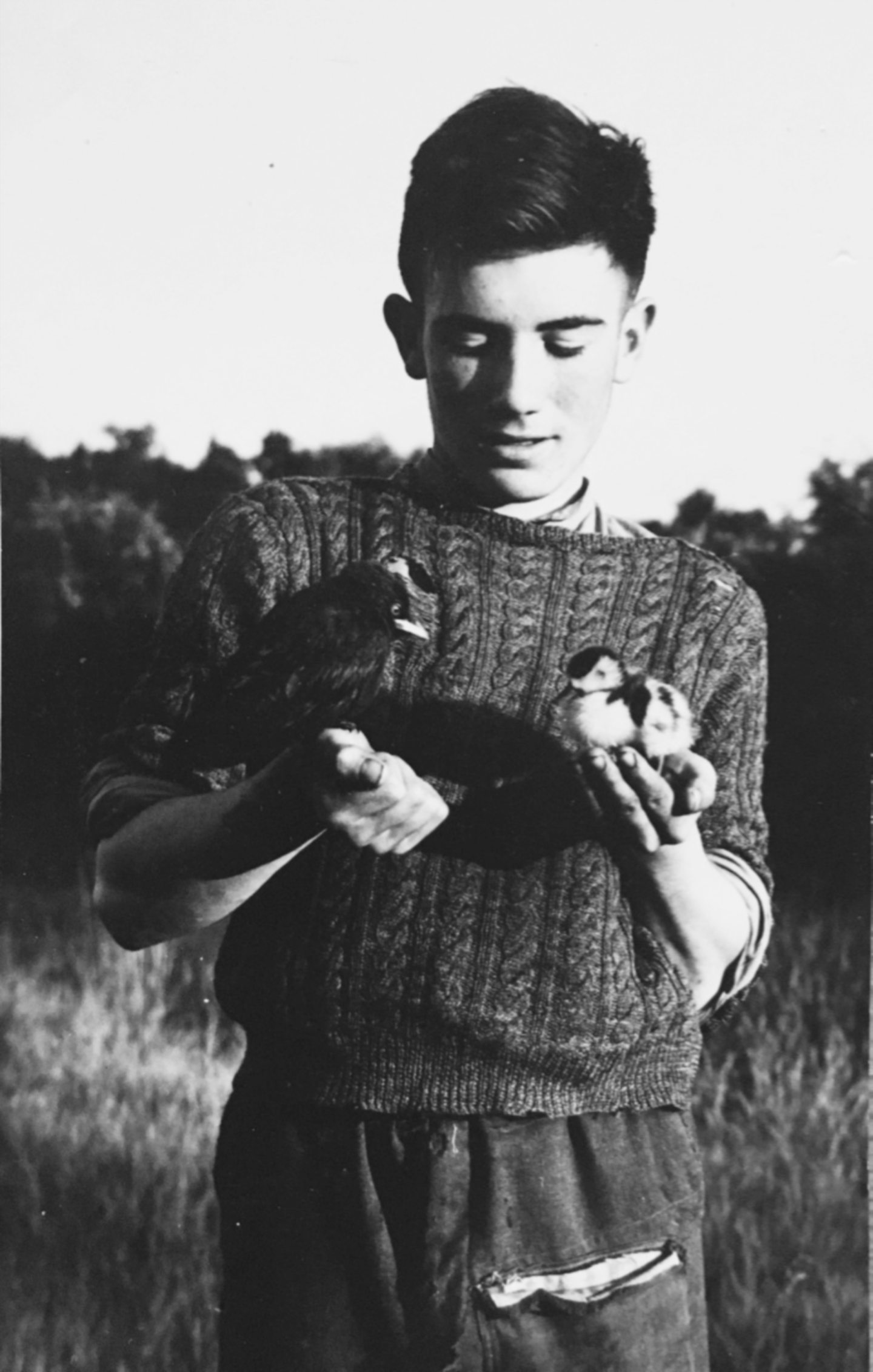

Roy’s passion for wildlife was sparked when he was growing up in southern Hampshire.

As a boy, he spent his days wandering the countryside collecting tadpoles, finding frogs and newts, or keeping a keen eye on the skies watching the birds.

Originally, he planned to study atomic physics but then was offered a job in an observatory ringing birds.

He took up the offer and has never doubted that decision.

“I just loved that,” he said. “And realised that’s what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

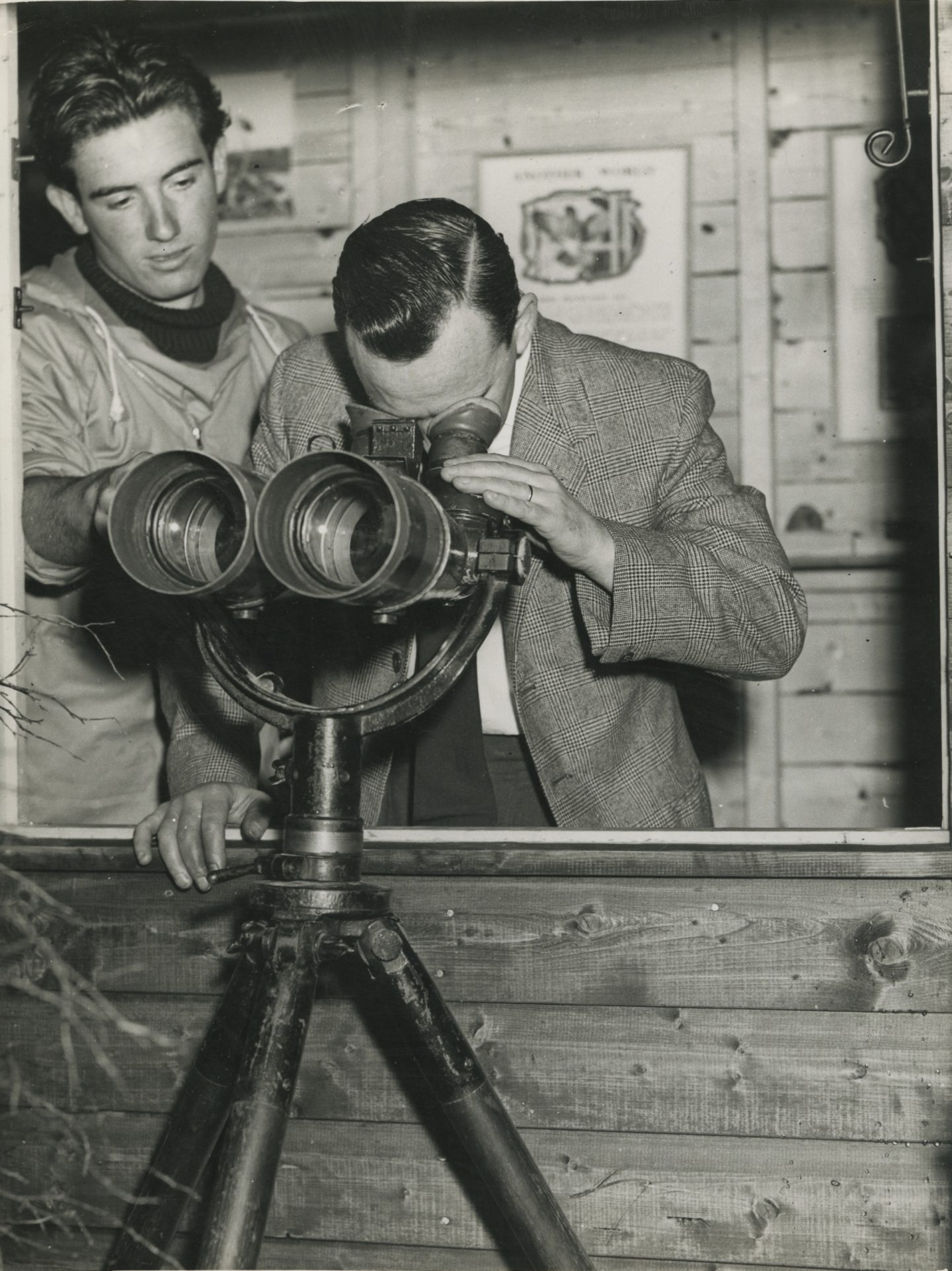

He fell in love with Scotland and made it his home after working on the Fair Isle as the assistant warden at the bird observatory in 1959.

Roy worked with the RSPB at Loch Garten before returning to the Fair Isle in 1964 to run the bird observatory for seven years.

He eventually ended up in Strathspey to run the osprey project and worked as the RSPB’s Highland officer. During that time he oversaw the management of nature reserves like Loch Garten, protecting nesting birds of prey from egg thieves and representing the charity.

In 1990, Roy decided it was time to start working independently to set up his own foundation.

And the Highland Foundation for Wildlife, which was later renamed the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, was established in 1995.

As well as appearing in a number of documentaries, and presenting BBC’s Autumnwatch and Springwatch, he has also broken ground with his satellite tracking studies, allowing the public to follow the journeys of the birds online.

The one bird Roy will never forget from all his travels

Over the years, Roy has worked with golden eagles, peregrines, and capercaillies to name but a few.

His work has taken him around much of the world, with projects in Spain, France and Switzerland, as well as being asked to advise on birds of prey in Australia and America.

Although he’s ringed many birds in his life, there is one golden eaglet from Cannich that he will never forget.

In 2018, the bird’s remains were discovered on a hillside in Sutherland — meaning it had lived to be around 33 years old.

The previous record for the oldest ringed golden eagle was in Sweden where the bird lived for 32 years. In Scotland, the oldest ringed golden eagle was 16.

This meant that the bird Roy ringed one day in 1985 had become the oldest surviving ringed golden eagle.

But, there was another special memory associated with this particular bird for Roy, who said he had “fun” ringing it with his eldest daughter Rona while she was studying at Aberdeen University at the time.

“Amazing,” he recalled. “It was amazing.”

While he says his work restoring the Scottish population of ospreys, and even bringing them back to England has been “important”, the reintroduction of the white-tailed eagle was “special”.

Over the last four years, Roy and his team have worked to help the white-tailed eagle to nest in Sussex, Hampshire and Dorset for more than 240 years.

He said: “That was really special to me because that’s where I grew up, and the idea that these great eagles had not nested there for 250 years are now back in southern England is just a tremendous feeling that we’d done well.”

Fighting for wildlife and changing public attitudes over the decades

Throughout his career, Roy has been a strong advocate for restoring lost mammals to Scotland, particularly beavers and lynx.

He was among those calling for beavers to be reintroduced in the early 90s and said it had been a “struggle”.

But now, the wildlife expert says it’s “fantastic” to see the large rodents being released in the Cairngorms.

Roy explained throughout his career, attitudes towards wildlife and the climate have changed, and he sees his life in three parts.

He laughed, and said when he was younger and wandering the Highlands to ring eagles and protect ospreys people thought he was an “unusual guy”.

And the 80s and 90s were a “hard time to be fighting battles”, with intensive agriculture and forestry work being carried out, and chemicals being sprayed.

“People just didn’t believe us,” he sighed.

“And it’s got so bad, all these floods are partly to do with what we’ve done to the planet and suddenly the work that I’m in and many other people are in is being recognised as important and not just a silly thing.

“I think it’s the time when we’ve got to show resolve and we’ve got to save animals and wild places, we’ve got to have plants so the pollinators can be there to look after our future.

“And I think what’s really good is that the young people are saying ‘look, we’ve got to get this done’ now.”

At 83, Roy is still ringing birds and is determined to finish two more books

At 83 years old, Roy no spring chicken anymore, but he still heads out to ring birds and check in on the various species he keeps a close watch on.

But, he says he is spending more time nowadays on his writing.

With three books already under his belt, he says he has two more that he wants to finish.

Not that he will be kept at his desk for long, because he is already eagerly planning a trip to see how the sea eagles are doing on the Isle of Wight in March and once the ospreys are back he will be checking on them just like he’s done for years and years.

And although he wasn’t expecting to be included in the Honours List, he’s proud of his achievements and has been touched by the many people congratulating him.

But, he stresses it’s important to recognise that the accolade is to do with their work, and the conservation of nature.

He finished: “My OBE, I think, has as much to do with the work that I and my colleagues do and the recognition that these things are now, not just important, but they’re essential to the future of the Earth.

“And I’m really pleased about that because it will encourage young people to do their best.”

Conversation