When Duncan Cormack was called up in 1942 he had never heard of the Royal Marines, but the commando training appealed and he was looking for excitement.

Within two years the teenager from Wick was in the thick of it, as a landing craft coxswain on D-Day.

He made eight trips to Gold Beach that momentous day in June 1944, the first before dawn broke.

His mission was to silently deliver Navy frogmen 50 yards off the coast where they swam ashore to clear the sands of enemy bombs and mines ahead of the main invasion force.

He was returning to his depot ship, the SS Empire Rapier, when all hell let loose and the assault began. Every gun on every battleship targeted the beach, scores of rockets soared overhead and soon casualties mounted.

On each journey they lost two or three troops the moment they disembarked: “They just collapsed, shot, machined gunned… there was nothing we could do for them – just reverse because another landing craft was behind me,” he recalled. “And so it went on like that, like buses, back and fore, back and fore.”

Mr Cormack, from Reay near Thurso, worked in NAAFI stores before joining the marines and training in Devon, Wales and the Firth of Forth. After exercises in Invergordon and gaining his coxswain’s qualification, he joined the Empire Rapier sailing to Southampton.

In the run-up to their D-Day mission, Operation Neptune, they trained along the Dorset and Cornish coasts but nothing prepared them for the tumult of June 6.

The following day, they repeated operations, shipping another 500 troops from Southampton, but this time without the accompanying gunfire. He made 30 trips over the following weeks, then sailed to Holland and Belgium. After VE Day he brought German POWs back to Southampton the Channel Islands before heading to Bombay on the infantry ship HMS Glengyle.

Following the Japanese surrender he was seconded to the Australian Navy and helped take troops to Kure in Japan, near Hiroshima, where he witnessed the devastating legacy of the atomic bombs.

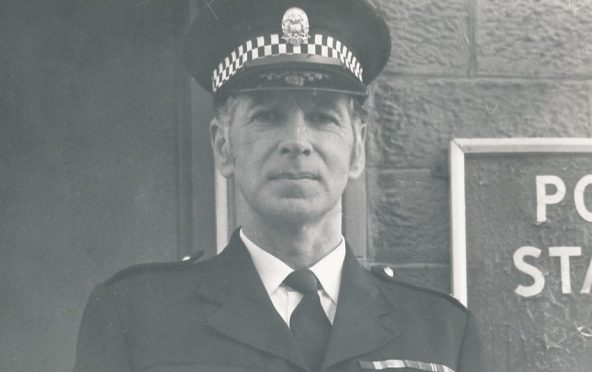

Demobbed in 1946, he joined Caithness-shire Constabulary, later Northern Constabulary, and spent 30 years in the force, serving at Wick, Castletown and Thurso. Retiring as a sergeant in 1977, he worked for a further decade as a driving instructor.

But one World War II incident had devastated Wick and in retirement he and his wife Elsie ensured it was never forgotten.

Wick was mainland Britain’s first victim of a daylight enemy raid. A total of 15 residents died, including 10 children, among them Elsie’s little sisters Amy and Bertha. Three months later two more children and a woman were killed in a Nazi raid on RAF Wick’s aerodrome.

Mr Cormack became a director of the charity Second World War Air Raid Victims – Wick and his wife served on the organising committee of its initiative to create a memorial garden which opened in 2010.

Last year Mr Cormack, also a Burma Star veteran, saw his own wartime courage recognised with the Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest award.

Mr Cormack died on December 28, aged 92. Widowed in 2013, he is survived by five children and seven grandchildren.