Some 16-year-olds today would feel lost with without access to their mobile phone or social media, while they take for granted being able to listen to the latest music or watching TV to see what their favourite celebrities are up to.

Life for 16-year-old Rena MacLennan was vastly different…

For most of 1943, she lived on a croft in Durnamuck, Dundonnell at Little Loch Broom in Ross-shire, where she kept a diary recording the day-to-day activities involved in a crofting community during the Second World War.

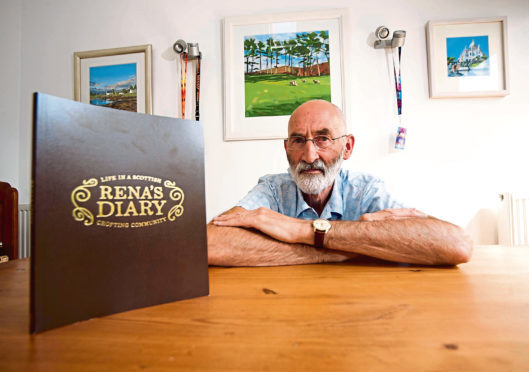

The diary forms the basis of a book entitled, Rena’s Diary: Life in a Scottish Crofting Community, written by her nephew Ken MacLennan, who was brought up on a croft near Durnamuck before the family left the area in 1962 and moved to Dingwall.

Ken, formerly principal teacher of Art and Design at Milne’s High School in Fochabers, is now retired and lives in Fochabers with his wife, Heather.

“Rena recorded the day-to-day activities involved in a crofting community; worked at seasonal jobs on local estates and lived close to the wartime proceedings taking place at Gruinard Island and at Loch Ewe,” said Ken.

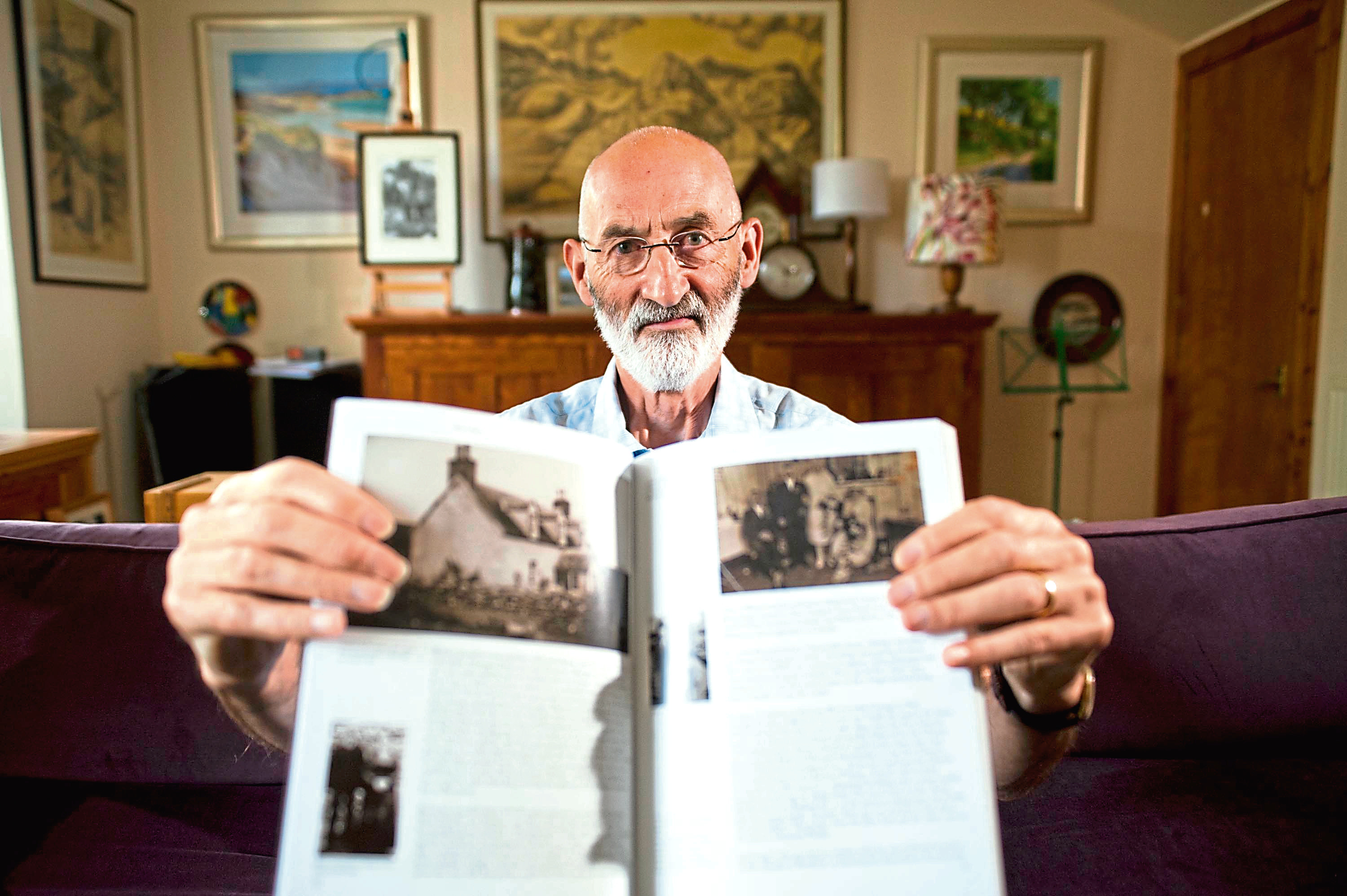

“The entries in the diary are annotated giving further information and added local history. The book includes photographs of the period, paintings and illustrations.

“Rena’s daughter – my cousin Kathleen – lives in the Isle of Wight and I don’t see her very often. During one visit about five years ago she brought along the wartime diary her mother had kept – I had no knowledge of it before that time,” said Ken.

“I was immediately fascinated and keen to know who the people Rena mentions in her diary were, what they did for a living and where they lived.”

When his cousin discovered Ken had become something of a family history detective determined to find out more, she loaned the diary to Ken, although it had a very important, physical connection to her mother.

“I was also interested in discovering what living conditions were like in Durnamuck 75 years ago so began gathering information from people who lived there at the time and people who still lived there.

“The hidden information in the diary started to rise to the surface. With their help, the words started to resonate. Small missing pieces of the jigsaw were now coming together making the picture clearer and more complete.”

RENA’S LIFE

Rena’s parents were Kenny and Mary MacGregor and she was the youngest of three. Born in 1927, she had an older sister Ella, then came her brother, Duncan, who was often called Sonny.

At what would be considered a very young age these days, Rena was allowed to leave school, aged 13 – which was one year earlier than the standard leaving age in those days. This was so she could support her mum Mary on the family croft.

Dad Kenny was often called away from home as he regularly worked at Dalmore near Alness where the War Office was building aerodromes and a seaplane base. Meanwhile, her brother Duncan was working at Department of Agriculture farms at Fearn harvesting food for the War Office. Sister Ella had a number of seasonal jobs before she headed south to join the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS).

The family lived in Honeysuckle Cottage, a charmingly-named crofthouse which was warm and secure but, compared to today, had very few facilities. There was no indoor water supply and no electricity. Water had to be fetched from a nearby stream using pails, while when darkness fell, candles and paraffin tilley lamps were used to provide light.

Although some coal was available, peat was the main source of fuel for both heating and cooking, the latter, along with baking, being done on a cast iron range with a wooden surround and mantelpiece.

Although rationing was in place, the family had access to essential foods but tea and sugar were in short supply.

And while today automatic washing machines and tumble dryers make light work of laundry, for Rena and her mum, it was a demanding household chore.

“All the washing was done by hand using cakes of soap, a washtub and a glass washboard. After being put through the mangle, which in itself could be an energy-sapping task, the washing was hung out to dry, or on wet days, hung on the ceiling pulley placed above the fire,” said Kenneth.

“Rena was not only involved in carrying out all the household chores but she was also hands-on with work outside the croft including taking the peat home, feeding animals, leading the horses at ploughing time, laying and lifting potatoes and a multitude of other day-to-day tasks.”

Much of her time was spent visiting family living in the area, including one set of elderly grandparents who lived next door with her aunt Irene, whose husband Murdo was a prisoner of war in Germany.

“She often uses the word ceilidh which we tend to think of these days as being a dance, but back then it meant a friendly visit from someone or a visit to another person’s house,” said Kenneth.

“At this time, there’s no phonelines here, and mail is the main form of communication.

“Rena, like everyone else, walks everywhere, although she recently started to cycle. The main mode of transport in this area has been by sea, and on land by foot or by pony. Rena and her siblings would think nothing of hiking miles over hills and moors to visit family and friends.”

RENA’S DIARY

At the end of 1942, Ella gave Rena a 1943 diary as a present. Although she didn’t write in the diary for the whole of that year, it nevertheless gives a fascinating insight into the everyday life of a teenager living through the war years.

Lots of the entries show a much simpler way of life.

In her first entry, for example, she speaks about her dad bating the small lines. “They used mussels to bait lines to fish for haddock, and used a boat to row across Little Loch Broom to fish on the Badrallach side,” said Ken.

During a cold winter, making a snowman with a cabbage leaf acting as a hat was important enough for her to record in the diary, while her dad putting on new soles to her brother’s shoes also came in for praise.

Food was simple then too and she refers to plain meals which included eggs, fish, lamb, scones, custard and prunes, while being sent a parcel of cakes was a real treat. In one entry for March, Rena writes: “I went up to the shop for my rations. He had no sugar but I got a 1lb tin of treacle and 1/2lb of raisins.”

Later that month she writes about receiving a parcel for her Auntie Katie containing, three tins of sardines, one tin of beans, two packets of pudding mix, soap and lard.

Hobbies included knitting a red jumper for herself and making a mat out of rags – a pleasant change from duties such as carting dung or tarring the lambs (a mix of tar and butter was mixed and applied to new lambs, partly to protect them against vermin and the cold weather).

SECOND WORLD WAR

At the point Rena started keeping her diary, it’s three years into the Second World War, and local travel restrictions have been put in place because of major Naval operations 18 miles away at Aultbea and Loch Ewe – the latter being used as both a fleet base and an assembly point for what would later be known as the famous Arctic Convoys.

Few people had cars then apart from the local nurse and hoteliers. The main traffic on the roads were military vehicles, visiting the camps at Aultbea and Mellon Charles.

“Much of the area was cloaked in secrecy,” said Ken. “A great deal of Royal Navy activity took place on the shore at Gruinard House – Rena’s first job was working as a maid in the house at Gruinard Estate owned by Sir Alexander Gibb and boats regularly came and went to Gruinard Island where it was later revealed they were conducting experiments with germ warfare.

“Locals had no idea until much later on.”

There was a checkpoint at Laide: a gun was sited on the Mellon Udrigle Road, while there was an RAF lookout station at Opinan. The sky over Aultbea and Loch Ewe was dominated by barrage balloons and the whole area around Loch Ewe, Aultbea and as far south as Gairloch was a restricted one.

“Military people outnumbered local residents three to one,” said Kenneth. “Convoys of ships sailed from Loch Ewe carrying badly needed supplies to Northern Russia. Several hundred service men and women, soldiers, sailors and airmen were based at Aultbea where the local hotel had been commandeered as staff HQ for 50 officers.

“The Gairloch Hotel was a requisition and used as a Naval Hospital.

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT

“After the war, Rena got work at a place called Eilean Darach, owned by a Mr Alexander and Mrs Rosalind Maitland, who also had a home in Edinburgh. She so impressed them that they asked her to move to Edinburgh with them,” said Ken.

“There, Rena was introduced to a very different way of life as the Maitlands were patrons of the arts and had a fine collection of work by artists including Monet and Cezanne. They’d even visited the sculptor Rodin to buy a piece of sculpture.

“Among the many famous guests calling at their home was the contralto singer Kathleen Ferrier.

“Here, Rena, a wee girl from Dundonnell, mixed comfortably with members of the high society, who all thought very well of her.”

In the mid 1950s, she married Murdo MacLennan, from Letters in Loch Broom, and they held their reception in the Dundonnell Hotel.

“They moved to their home and croft at Letters where Murdo worked for the Forestry Commission and Rena ran the Post Office from the front room of their house.

“They had two children, Murdo and Kathleen. Rena was a very kind and considerate person who was very helpful to the local community, especially to her elderly neighbours who knew that Rena would always be glad to keep a watchful eye out for them.

“She continued to keep the ‘ceilidh’ attitude alive with friends regularly visiting the house and Murdo would be persuaded to bring out his accordion. Although people had very little they were content, as theirs was a rich life.”

Rena died in 1981.

“It was never my intention to write a book, but having undertaken research I discovered there was a lot of wartime activity in the area, and while there’s lots written about what happened at Loch Ewe, not much had been written about what happened in Little Loch Broom and Dundonnell.

“The more I investigated, the more I was drawn in by the diary.”

Rena’s Diary is on sale in The Gale Centre, Gairloch; Laide Post Office; Ullapool Museum; Ullapool Bookshop; The Ceilidh Place Bookshop in Ullapool, Picaresque Books, Dingwall; the Ullapool Bookshop and at www.boco.org.uk