Chilling predictions have been made for Arctic polar bears and other large predators by an Oban scientist.

The bears rely on seasonal sea ice as their habitat on which to travel and to hunt – but the true extent of their reliance has only just been discovered.

Thomas Brown, of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (Sams) at Dunstaffnage, made the findings and warned last night that more work needs to reduce carbon footprints to reduce the impact of sea ice loss.

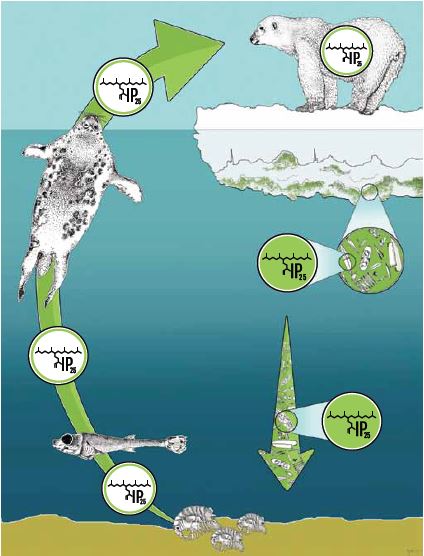

Mr Brown has devised a technique that traces a chemical in the food chain, known as IP25, to determine how much of an Arctic animal’s energy is derived from sea ice algae at the base of the food chain. It paints a bleak picture for many large Arctic predators.

Species such as ringed seals and the polar bear rely heavily on the production of microscopic algae that grow underneath the sea ice. The algae are eaten by zooplankton and this energy works its way up the food chain to the region’s top predators.

While looking at three polar bear communities in the Canadian Arctic, Mr Brown showed that up to 60% of polar bear prey was made up of ringed seals. Consequently, on average, 86% of polar bear energy was being derived from sea ice algae, as opposed to open ocean algae.

Mr Brown said: “Polar bears rely on sea ice as their habitat. Consequently, conservation assessments of polar bears identify the ongoing reduction in sea ice to represent a significant threat to their survival. However, the additional role of sea ice as an indirect source of energy to bears has been overlooked.

“The polar bears’ reliance on carbon (energy) derived from sea ice algae was surprisingly high and shows that the reduction of sea ice means more than just a loss of habitat. It threatens the success of the entire food web in the Arctic as we know it.

“We know that carbon from sea ice algae is important for Arctic animals, but we need to quantify how much of that carbon is consumed in order to understand the full impact of sea ice loss.”

Mr Brown believes his scientific technique can now be used to establish long term monitoring of Arctic animal diets, which could inform future conservation measures.

Sea ice cover in the Arctic circle is generally decreasing year on year. The four lowest winter maximum ice extents ever recorded by satellite (1979-2017) occurred 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.