As midnight approached on October 14, 1939, there was no reason for the crew of the Royal Oak to believe they were in any peril.

The majority of the 1200-plus crew were sleeping below deck, while a few others on watch enjoyed a spectacular display of the Northern Lights over Scapa Flow on Orkney.

The men were in the middle of Britain’s greatest naval base and although the Second World War had begun, there had thus far been little large-scale conflict.

Yet, in the course of the next two hours, all hell erupted at the site and 835 men and boys died when the vessel fell victim to an audacious German U-boat attack.

Even now, as commemorations begin to mark the 80th anniversary of the tragedy, the seismic impact of the destruction is still being felt.

Indeed, the official death toll has risen from 834 to 835 after it was confirmed that a young seaman from the Royal Oak had succumbed to grievous burns injuries in Cromarty Hospital on October 27, 1939.

Gareth Derbyshire, chairman of the HMS Royal Oak Association, lost his grandfather, leading seaman Ronald Derbyshire, in the attack, and recalled how the news had left an indelible impression as the scale of the tragedy hit home.

He said: “My family actually received a letter from my grandfather on October 18 in Burton-on-Trent.

“It was full of matter-of-fact conversational details, just a typical letter you would send to your loved ones.

“That was probably the last letter he ever wrote. Within a few hours of it being posted, he was among the hundreds of men who were killed.”

How did the HMS Royal Oak sink?

In 1938, with the threat of war looming, surveys showed that Kirk Sound (part of Holm Sound) had a perfectly clear and deep passage running through it.

Some 300 to 400 feet wide, it posed a real danger to British ships stationed in Scapa Flow, but it was concluded that the sounds would be too hazardous for a vessel passing through on the surface.

It was a fatal misjudgement and Kapitanleutnant Gunther Prien, the commander of German submarine u-47, demonstrated the inadequacy of the British fortifications when he launched one of the most daring attacks in naval history.

HMS Royal Oak had returned early from the Home Fleet sweep and took up its role as anti-aircraft defence for the Scapa Flow anchorage.

Nobody seriously expected they would come under enemy attack in their own backyard.

However, U-47 approached Scapa Flow through the narrow approaches at Kirk Sound with surprising ease.

It was high tide and a little after midnight on October 14. When the first torpedo struck HMS Royal Oak at 12.58am, the dull thud confused the sailors.

They thought the muffled explosions were an on-board problem such as an explosion in the paint store. They certainly did not think it was a U-boat attack.

A second salvo failed to deliver a hit, but the confusion allowed the Germans an additional 20 minutes to return to their firing position, reload, and fire a third torpedo.

This was perfectly directed and sparked the ensuing carnage.

Such was the ferocity of the explosions, the ship heeled over alarmingly and all the lights went out.

It had been fine weather, so the ship’s hatches were open. Water crashed through the vessel and men asleep in their bunks were unable to get out in time.

It took just minutes for the battleship to sink.

How many died in the tragedy at Scapa Flow?

Hundreds fought for their lives, trying to swim for shore through thick fuel oil and in freezing temperatures.

A total of 835 men perished, while 400 were rescued.

Many of the men are buried in the Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery on Hoy.

Mr Derbyshire said: “It was a stirring piece of commanding from Prien – obviously I wish he had never succeeded and it impacted on so many people, but he saw an opportunity to penetrate the defences at Scapa Flow and he succeeded.

“It must have come as a bolt out of the blue to all those on board. So many of the sailors were from Portsmouth. So many of them were so young.

“That’s why we should never forget and why it is important a large number of second and third generation family members are taking an interest in the commemorations.”

In a film recording, where Prien discussed his actions, he said: “Inside Scapa Flow, the harbour of the British sea force, it was absolutely dead calm.

“The entire bay was alight because of bright northern lights in the region.

“We then cruised for approximately one and a half hours, chose our targets and fired our torpedoes. There was a bang and, in the next moment, the Royal Oak blew up.

“The view was indescribable. And we sneaked out, in a similar fashion as we got in, close past the enemy guards, and they did not see us. You can imagine the excitement and happiness we all felt at achieving our task.”

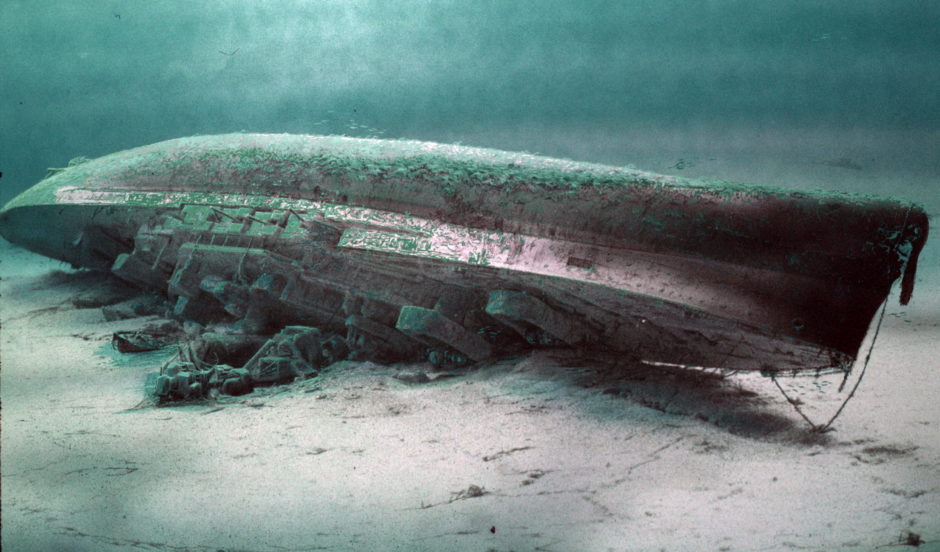

The wreck is now a designated war grave, but Royal Navy divers have carried out recent surveys at the scene where the Royal Oak descended to her watery grave.

As Mr Derbyshire added: “The Royal Oak might have been destroyed, and the last survivor [Arthur Smith] might have died [in 2016], but the relatives of all those who were lost will always remember those who fell.”