The call of seabirds and lapping of waves were the only sounds as 36 people looked back towards home before clambering aboard.

St Kilda, for all its rugged beauty, could no longer sustain a community, and so its remaining residents had a choice to make.

Just as fellow islanders moved to Canada and America in search of a better life, St Kildans relocated to the mainland in a bid to survive.

The remote archipelago had seen generations make a living from the land and sea, and fight back against outbreaks of disease.

It was, in fact, the steady creep of the modern world which contributed towards their decision to start again elsewhere, on August 29 1930.

The community had penned a letter in May of that year, petitioning to leave.

The National Trust for Scotland (NTS) took over in 1957 and a dedicated team of researchers, archeologists and rangers have arrived on St Kilda in the passing decades in a bid to uncover fragments of the past.

The island is the UK’s only dual Unesco World Heritage Site and home to nearly one million seabirds – including the UK’s largest colony of Atlantic puffins.

The evacuation is but one chapter in an ever-unfolding story, for there is no place quite like St Kilda.

Around five thousand visitors would normally descend on the island each summer. Yet just as on this day 90 years ago, there is only the chorus of wildlife on the breeze due to the current pandemic leading to the temporary closure of the island.

Aside from a maintenance man, who only made it out to St Kilda earlier this month, the site has once again been left to nature.

The important recording of data surrounding seabirds has not taken place, and the work of NTS has been completely disrupted.

The team will not be visiting until spring next year, in a bid to start once more with the careful preservation of this extraordinary place.

And yet the spirit of St Kilda will clearly rise again, for it has inspired a passion in those who have explored the fascinating remains of the village and surrounding land.

We spoke with experts who believe St Kilda to be home, wherever they are in the world.

Susan Bain

Susan Bain has been visiting St Kilda for 18 years due to her work with NTS.

She is currently Western Isles manager, and helps look after several islands in the Outer Hebrides – including St Kilda.

Although staff are not based on St Kilda all year round, Susan would normally visit every summer.

The pandemic means she has been forced to work from home in Inverness, although her love of the island clearly remains intact.

“I was an archeologist for several years, then I started with NTS as an archeologist in the Cairngorms,” said Susan.

“Then the position came up to be an archeologist on St Kilda, which I did for four years.

“When we talk about archeology, it’s not excavation. It’s monitoring the condition of buildings.

“St Kilda is one of the most densely packed islands I’ve ever come across in terms of buildings. There are hundreds of cleats, which are storage huts made out of dry stone dyke.

“Then there are the old black houses, the graveyard and church alongside kilometres of dry stone dyking.

“We’ve built up a database of everything, what it is and where it is located.”

Despite St Kilda’s enduring appeal, Susan believes life on the island is not for everyone.

The site is often described as the edge of the world, and with good reason. It is the most remote part of the British Isles, found 41 miles west of Benbecula.

The archipelago consists of the main island of Hirta, along with Boreray, Dun and Soay, and the sea stacks Levenish, Stac Lee and Stac an Armin, which, at 626 feet, is the highest in Britain.

The islands form the most important seabird breeding station in north-west Europe, and even boast the world’s largest colony of gannets.

“You have to be outdoorsy to stay here for any length of time,” said Susan.

“Carrying out any kind of work here is challenging, because it’s incredibly hilly.

“You can’t be scared of heights and you have to prepare yourself for the fact that seabirds may dive bomb you, especially if they are nesting.

“I first came to St Kilda in 2002, I had been working in Egypt. I was in Cairo, one of the most densely populated cities in the world. It was a huge contrast.

“From the moment I arrived, St Kilda felt familiar to me.

“It’s quite a small island, only two miles across. But it feels huge, you get fit very quickly.

“You’re living with the wildlife right beside you, your life is dominated by the weather. There are some days where you think, is there even going to be a boat or a helicopter today? Will there be a food delivery?

“You have to take absolutely everything with you, from the tools you might need right down to washing-up liquid.

“It makes you think, what must it have been like to live there?”

Susan believes there may never be a definite answer as to the first inhabitants of St Kilda, who would have come across the island by accident.

While life would have been incredibly difficult for residents, there is no doubt that a community flourished.

“You can see St Kilda from Harris, it is on the horizon,” said Susan.

“It is unlikely that people came here deliberately, they wouldn’t have had the technology for starters.

“Today we look at St Kilda and think life would have been so harsh. But there is everything you need here to survive.

“The community had agricultural land, so they could plant crops and keep animals.

“They would also have been attracted by the seabirds, both for their eggs and meat. You wouldn’t have gone hungry.

“Yes, at times it would have been hard. The story of St Kilda has been dominated by the evacuation, yet people lived here for thousands of years.

“It was a series of circumstances which led to the departure, and the fact that St Kilda became more isolated as transport modernised.

“It was no longer on the main shipping route because the world was changing.

“Life was hard if you were poor across all of history.

“Would you rather be poor in the Gorbals in Glasgow, or poor on St Kilda in the early 20th Century?

“I’d choose St Kilda every time.

“I can’t imagine a life where I don’t go to St Kilda again because it’s such a special place.

“I can’t even explain why, it just gets under your skin – to realise the unique culture of the people who lived there and called it home.”

Wildlife is a huge draw of St Kilda, and the team had just started work with artificial nest boxes before the pandemic hit.

“We have no idea if the puffins have done well this year, or any of the seabirds for that matter,” said Susan.

“There are 17 different species, but we haven’t been able to do any research. So a whole year’s worth of data has been lost.

“Puffins can easily live into their 30s; we found a puffin which had been ringed 38 years ago.

“Seabirds have been coming to St Kilda forever, because it is the perfect geology for them. There is a range of habitats, think of the cliffs as you would a high rise.

“The razorbills are at the bottom, with fulmars towards the top.

“It’s not just the housing that’s great, there’s a rich ocean as well.”

Some species are struggling however, and Susan believes that global warming is partly to blame.

“Kittiwakes are a beautiful little gull species; numbers have declined 98%,” said Susan.

“It is horrendous and we’re not sure of the reasons why.

“The seas around Britain are warming, fish and plankton are sensitive to temperature.

“So they either go deeper to find the cooler temperature, or they move further north

“If you can dive to 40/50ft, you’re fine. If you’re a kittiwake, you can only dive 6ft and your prey is out of reach.”

One thing which does go in the favour of seabirds on and around St Kilda is that there are no ground predators.

There is a strict bio-security policy in place, to prevent rats from reaching the island.

This includes only allowing open boats to sail to St Kilda, and all items which come ashore are checked.

Susan may not be able to visit this year, but St Kilda is never far from her mind.

“St Kilda is one of the most amazing places in the world,” she said.

“For people living in Scotland, it tells us who we are and where we have come from.

“It’s very important for us as humans to understand that people did things differently.

“It might not be better, but nor is it worse.

“Ultimately I think St Kilda can teach us a lot about sustainability.”

Derek Alexander

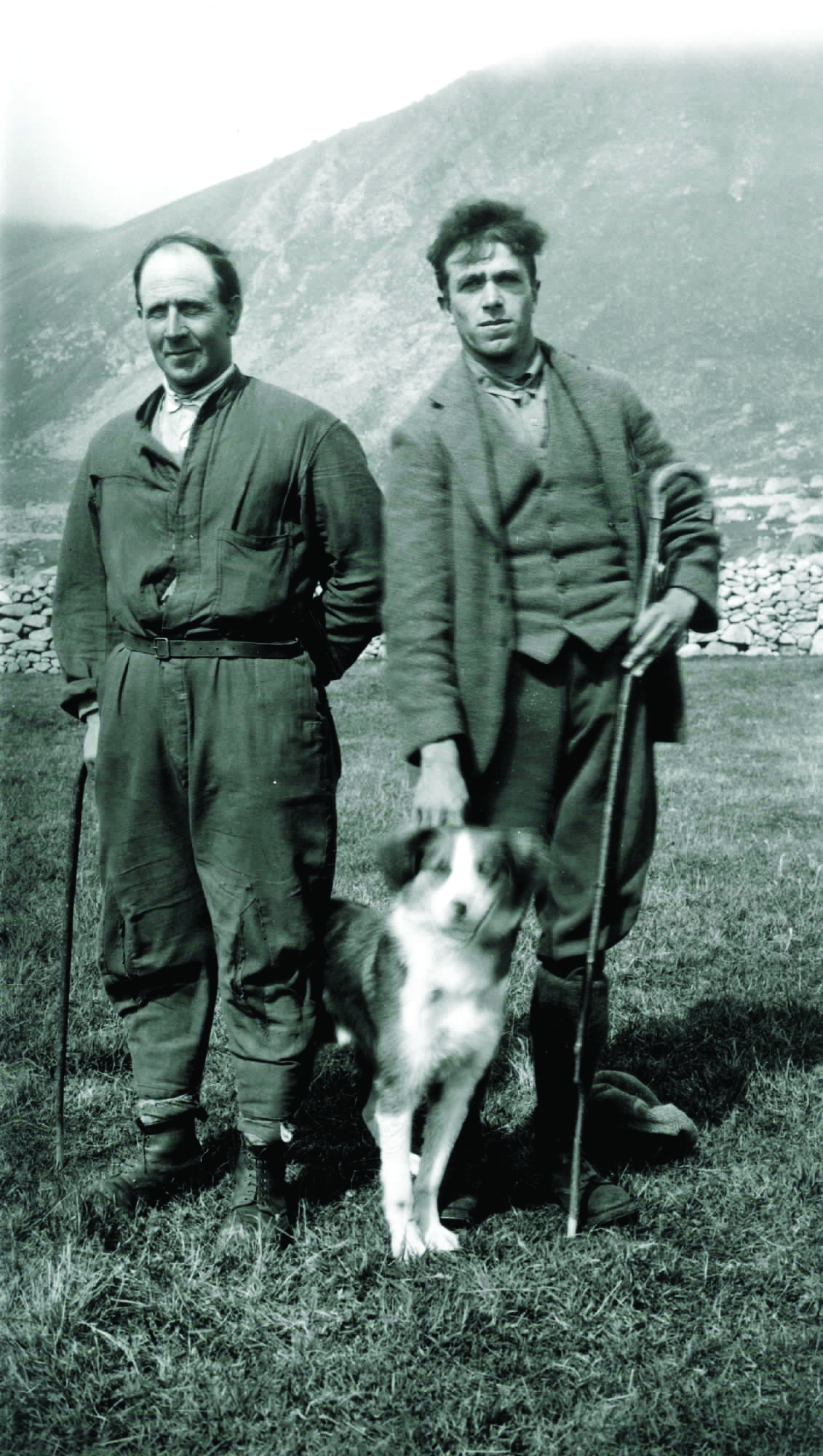

Derek Alexander also holds the island in great affection. As head of archaeological services for NTS, he decides which sites require further investigation.

Naturally, St Kilda has a place on the list, and Derek believes everybody should have the opportunity to visit.

“I remember travelling by helicopter from Benbecula, it’s like scenes from Jurassic Park when you see the island on the horizon,” he said.

“You fly in from around the bay for this dramatic landing at the water front.

“The thing that really got me was that I hadn’t understood the scale. That’s what took my breath away. You see very green grass and very grey stone, it’s quite a contrast.”

One of the main challenges of Derek and his team is protecting the stone walls, which were built and rebuilt by generations.

“People are drawn to the fact that it was dramatically abandoned, but for most of its history, St Kilda was home to a thriving community,” he said.

“We don’t know how long people stayed, but the population in the early 18th Century was around 100.

“An outbreak of small pox in 1727 reduced the population to 30.

“It’s difficult to know how many people are buried in the graveyard, as a lot of the stones are unmarked.

“We know that the minister was a key figure in the 19th Century, and there were originally three chapel sites.

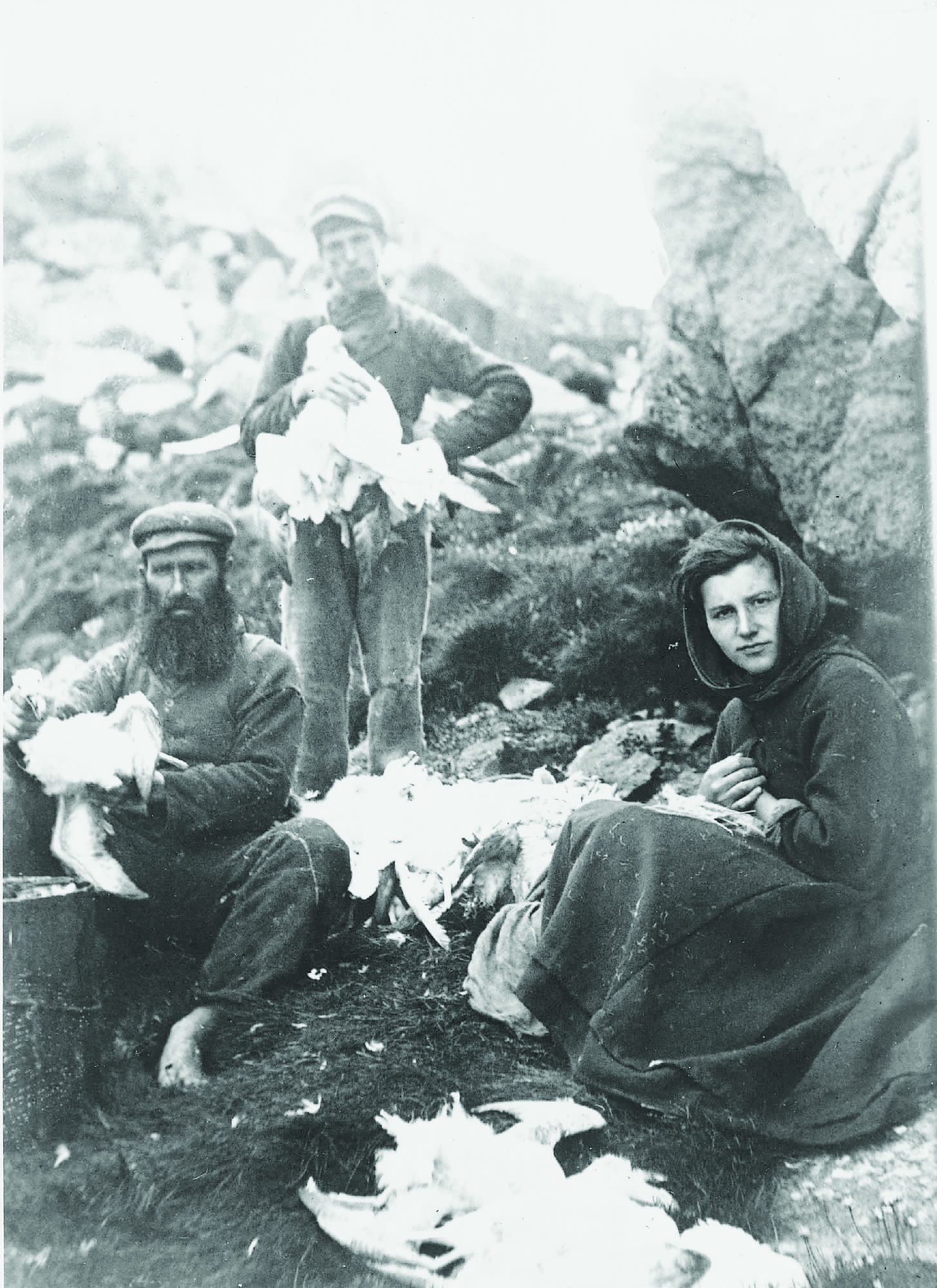

“The cleats are fascinating, we think they were used for storage. People would catch seabirds and collect their eggs and feathers.

“Feathers were used for producing oil and for paying rent, as they were collected and traded off. It’s the adaptation to the setting which is remarkable, because people did very well for quite some time.”

Julie Hunt

Julie Hunt, who is chairwoman of the St Kilda Club, believes her visits have changed her life.

The club was formed in the ’50s and is now a charity to help conserve and protect the islands of St Kilda and raise public awareness.

Julie, who lives in Norfolk, visited St Kilda as part of a work party in 2002.

She has returned four times, and believes it is a second home.

“Every time St Kilda comes into sight, it is like I am seeing it for the first time,” said Julie.

“It still has that magic and a mystical atmosphere.

“All my visits have given me time to think. I even started my own business after one trip because it puts things in perspective.”

Although life St Kilda can be romanticised, it was brutal.

“There was a high mortality rate for babies, they fed them using the stomach of a fulmar,” said Julie.

“I think one baby out of eight survived.

“During the winter it would have been dark for most of the time, and you were sharing your house with livestock.

“I’ve learnt a great deal from so many people during my trips. The club has just under 1,000 members, with one thing in common.

“We have an enduring love for the edge of the world, for St Kilda.”