On a clear day, the bog at Forsinard stretches as far as the eye can see, in a vast mosaic of greens and browns in every direction.

Known as the Flow Country, the tallest vegetation here barely reaches knee height and the wind whistles over the lumpy ground all year round.

It may lack the picture postcard beauty Scottish landscapes are famous for, but the Flow Country is far more than a pretty face and has been compared to the Amazon for its ecological importance.

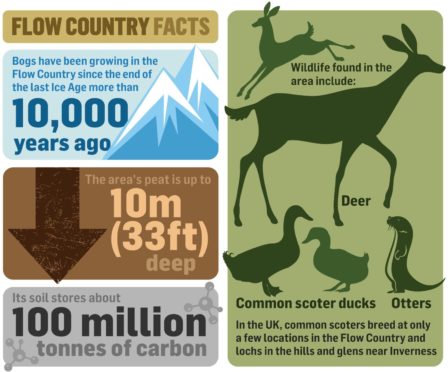

Beneath the moss and the mud lies one of the planet’s largest surviving expanses of peat – a carbon-dense mass of partly decomposed organic matter. And here lies the peatland’s hidden strength: an extraordinary ability to absorb and store carbon.

By locking away carbon for hundreds – and sometimes even thousands – of years, peatlands have become an important resource in the fight against climate change.

“Peatlands don’t cover a big area of the planet, only about 3% of the world’s surface,” said Roxane Andersen, a leading global peatlands researcher and professor at the University of the Highlands and Islands.

“But they store approximately a third of the land’s carbon – twice as much as all the world’s forests combined.

“When you put that into perspective, they become the most efficient ecosystem in terms of carbon storage on the planet.

“The other thing that’s really important, is that the carbon stays in the peat for so long.

“I mean, if you leave it alone long enough it will become coal. We’re not talking two or three years or even two or three decades, the peatlands in Scotland have been storing carbon for 10,000 years.”

Essential but long overlooked

However, in Britain and beyond people have been draining large swaths of peatland and converting it to pasture or crop land for centuries.

In fact an estimated 80% of Britain’s peat bogs have been damaged or destroyed.

But the tide appears to be slowly turning, and as of 2021, Scotland is leading a global peatland restoration movement, with the programme at Forsinard among the largest of these efforts.

Roxane, 40, has been working on the Forsinard reserve since 2012 as the area’s only peatlands scientist.

Traipsing across the formidable bog, Roxane found herself slowly adapting to the landscape just like the hundreds of specialist plant and insect species which call this isolated place home.

Originally from the outer suburbs of Quebec City in Canada, she moved to Scotland to study biochemistry in Aberdeen, then, in her own words, “accidentally came into the world of peatlands and never looked back.”

Roxane has been at the heart of everything the reserve is doing to ensure the peatlands’ place in 21st century Scotland and beyond.

This includes extensive research into peatland resilience and land management, as well as taking a leading role in the bid to have the Flow Country recognised as a site of outstanding natural importance and granted Unesco World Heritage status.

But perhaps most of all, Roxane is acutely aware of the need to raise the profile of peatlands.

The 494,210-acre expanse of peatbog, lochs and bog pools that make up the Flow Country stretches across Caithness and Sutherland, covering an area more than twice the size of Orkney.

But many people are unaware – or simply uninterested – in its importance.

“There is this perception that trees are good and that the Amazon is the lungs of the planet, even if people don’t really understand why,” said Roxane.

“Peatlands do exactly the same job as trees except they do it better and over a longer period of time.

“However if you’re in a forest, all of the things the trees do for the planet are visible and in your face, you can’t not notice the trees and all the diversity there because it’s right in front of you.

“Whereas if you were in a peatland, most of it is happening underneath your feet, so it’s not visible.”

She mentions that peatlands have traditionally been associated with unpleasant things, like midges or getting trapped in mud. In The Lord of the Rings, peatlands are referred to as marshes of the dead.

“It can be difficult to break that image of peatlands being not very nice places,” she said.

“It takes time to appreciate peatlands and a bit more understanding. They aren’t an easy sell compared to some other ecosystems, like rainforests.

Under threat

Unlike rainforests or coral reefs, peatlands have largely been ignored by researchers and policymakers.

Historically, they’ve been seen as wastelands that can be conveniently converted into agriculture, since people don’t usually live on them.

But when peatlands are excavated to be turned into other land uses, this degrades the quality of the land and releases huge quantities of stored carbon into the atmosphere.

“The degradation of peatlands releases huge quantities of carbon very rapidly,” said Roxane.

“Anything which disturbs the delicate balance of the ecosystem turns them into carbon sources rather than carbon stores.

When peatlands are drained, the compressed organic matter begins to decay, turning long-submerged carbon into carbon dioxide and adding more greenhouse gases to our already overheated atmosphere.

Drained peatlands also become susceptible to burning – and when they burn, they are extremely difficult to put out.

In 2015 Indonesia’s peatlands burned en masse after years of draining and deforestation.

Thanks to the carbon stored in the ground, the fires spread a toxic yellow haze over much of the region and released more than 800m tonnes of CO2.

“It’s not even just about the carbon,” said Roxane. “It’s also about the incredible biodiversity peatland ecosystems support.

“There are countless species which are highly adapted to these specialised conditions and can’t live anywhere else.”

Hope on the horizon

The Scottish government’s climate change plan aims to restore 250,000 hectares (617,800 acres) of peatland by 2030.

This makes Scotland a world leader in implementing large-scale peatland restoration, and the budget allocated to the cause – a cool £250 million – reflects how seriously the government is taking the project.

“Investment on this scale is not replicated anywhere else in the world,” Roxane said.

“So there is money there, but there is also a lot of work to do and we need to find ways to make sure the resources are located at the right place now so that in the future we will be in a better position.”

She explains that peatland restoration is possible, even on land cleared for forestry or agriculture, but that it has to happen quickly if we want these areas to be in the best possible condition to deal with future cycles of fire, flood or drought we might experience as a result of climate change.

Time is clearly of the essence and millions have already been spent so far, including more than £10m for restoration work at the Forsinard Flows reserve.

If they can be restored to health, Roxane and other scientists believe that the peatlands will endure for many thousands of years to come.

“Peatlands naturally are extremely resilient, that’s why they’ve been here for such a long time,” she said.

If she is right, the health of the planet may well just come to rely on the health of the mud beneath our feet.

Professor Roxane Andersen is giving a free seminar today at 4pm to mark World Peatlands Day. The online talk will explore the science of peatlands, touching on subjects including climate change, biodiversity and restoration.

For more information, visit the UHI website.