The Scottish government has insisted it recognises the critical need to attract new crofters in order to safeguard the future of North Uist.

It says young people are finding it hard to get into crofting but moves afoot including £50,000 grants to encourage young people and families to remain on, or move on to islands, will help safeguard the way of life.

Responding to an island student so moved by the crisis he turned his final year university project into a rallying cry, the government said it knew many island communities would not exist without crofting.

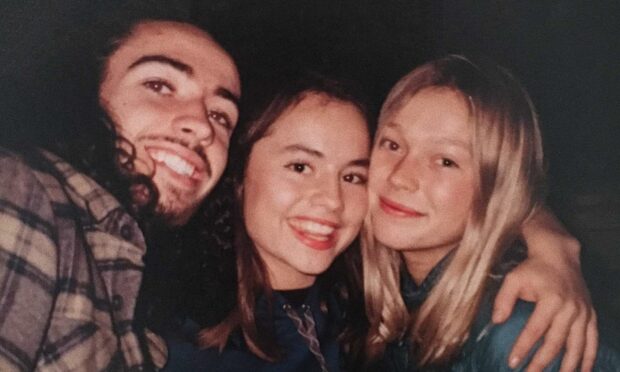

It comes after Glasgow School of Art Innovation School student Calum Ferguson rested his focus on the challenges young people face trying to get into crofting.

While Crofting Commission figures for 2019 and 2020 say 830 new entrants got into into crofting – 32% under 40 and 44% women, a survey shows nine out of 10 crofters are concerned about the lack of crofts available for use by new entrants to the sector.

With a view to joining that chorus, Calum used his final degree project to “ignite a conversation around the lack of access to crofting for young people and new entrants”.

As a student of The Innovation School, a centre for design teaching that applies Design Innovation to the key issues defining contemporary society, Calum put it all in to the mix.

He considered the impact the Covid pandemic was having on young people already hit by a housing crisis.

And he also aimed to focus on the toll climate change is taking on the island.

“I wanted to raise awareness of the urgency for innovation and reform to allow young people to thrive in crofting communities,” he added.

Crofting legacy

As part of his project, Calum has created a series of contemporary talismans.

They recall the traditional Athurachadh that act as custodians of land, holding the responsibility to see that croft is used appropriately.

They act, he says, as “a point of conversation about the passing on of crofts, and the continuation of the culture”.

He adds: “The talismans of Athurachadh create a legacy for older crofters in passing land on to the younger generation.

“They give a duty of care for crofters to think about how that land is best used to take into consideration local traditions and culture, and also benefit local and global human, and non-human populations, as well as the environment.”

‘Too difficult’

The government has responded to Calum’s call saying young people undoubtedly are finding it hard to get into crofting.

It says it is encouraging diversification into agri-tourism, woodland regeneration and creation, local food networks, and restoration of degraded peatlands, to try to safeguard the way of life.

It is also offering 100 bonds of up to £50,000 to young people and families to stay in or to move to islands threatened by depopulation.

A spokesman said this “will be a key intervention in meeting our commitment” to repopulate rural areas.

He says: “We recognise that the creation of opportunities for young new entrant crofters is challenging.

“We will continue to work with the Crofting Commission and other key stakeholders to explore new ways to ensure that entry to crofting is more accessible for new entrants.”

He adds: “In many cases rural and remote rural communities would not exist if it was not for crofting.

“We value Scotland’s farmers and crofters for the work they do in putting food on our tables.”

Rules and regulations

Crofting tenure requires crofters to live within 19 miles of their croft and to provide their own housing.

The government said it has, since 2007, approved grant payments of more than £22.1 million.

These payments have helped to build and improve more than 1,030 croft homes through the Croft House Grant scheme.

For further reading, see the National Development Plan for Crofting, published in March.

North Uist influence

Calum’s fellow students’ work was also guided by the island.

Tara Drummie’s ongoing Harvesting Light photographic project is “motivated by the symbiotic relationship between human beings and the land”.

It was inspired by crofters who encourage the rare and bio-diverse machair ecosystem, prevalent on the Isle of North Uist, to thrive.

Tara adds: “Through my work I want to motivate my audience into reducing any exploitative behaviours they have towards the land, encouraging attitudes of respect.”

Silversmithing and jewellery student Iona Turner has created a collection crafted from the knotted wrack seaweed thrown up by the waves on to the island beaches.

She has combined the seaweed with brass, recycled silver, hemp cord and bio resin.

“For my Seaweed Gatherer collection I immersed myself in the seaweed’s wild ecology,” says Iona.

“By becoming familiar with seaweeds and the ecosystem in which they exist, our relationship with these non-human species can develop.”