It wasn’t long ago that passengers asking if the ferry between Eriskay and South Uist was going to sail received the non-committal reply “very likely”.

The irregular service caused by unpredictable tides dominated island life, affecting everything from job and education opportunities to medical services and tourism.

It also increasingly added to the island’s sense of isolation and peripherality, leading to a campaign for a fixed link to reverse chronic decline.

On July 12 2001 the ferry made its final ten-minute crossing and islanders could instead walk or drive over a mile-long causeway.

Fears for island population

Eriskay is renowned as the place where Charles Edward Stuart landed to launch the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion.

It was also where the SS Politician grounded in 1941, leading to islanders ‘liberating’ some of the 260,000 bottle of whisky on board, inspiring Compton Mackenzie’s book ‘Whisky Galore’.

But by the millennium it was known as the only inhabited island in the Western Isles without a land link to its nearest neighbour.

There were real fears that another island population could disappear in a similar way to communities such as Mingulay, Scarp, Taransay, the Monach Isles and St Kilda.

Eriskay, known in Gaelic as Eilean na h-Oige – the isle of youth – had a dwindling population which fell from 421 in 1931 to under 140, many of them elderly.

The tidal ferry was a barrier to economic growth, investment and tourism.

It prevented people in Eriskay having jobs off island.

Secondary pupils had to stay all week in a hostel in Benbecula, beginning an exodus which continued into higher education and employment.

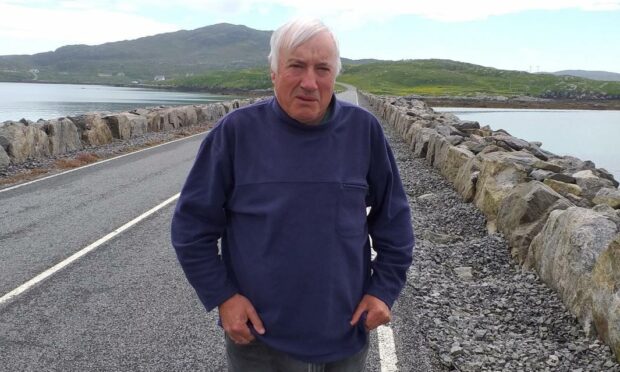

Neil MacDonald, former headmaster at the island school and a past community council chairman, was at the forefront of the causeway campaign.

He believes the new fixed link changed the landscape in more ways than one.

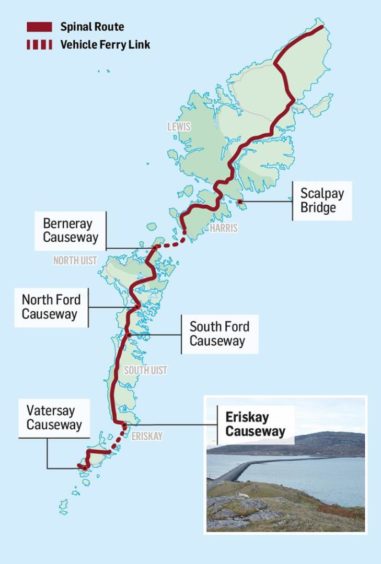

The £9.4 million causeway and associated Sound of Barra ferry linked Eriskay into a chain of infrastructure running the 135-mile length of the Outer Hebrides.

Causeway has helped change island demographics

Residents could take jobs in Uist and beyond and secondary pupils could travel daily to school.

The hospital in Benbecula became accessible by road, deliveries and social and cultural visits were easier.

Visitors to Eriskay’s shop, church and pub were more regular and numerous.

The population remains at just under 140, but the demographics have changed.

Families have returned to live on the island, new houses are being built and self-catering units have sprung up to cater for a new influx of visitors.

Mr MacDonald said: “Before the causeway you couldn’t live in Eriskay and work on Uist. It was just an impossibility. So no young families were able to move here.

“That has totally changed because of the causeway. There are lots of people from Eriskay who work on Uist now. Very quickly after 2001 we had quite an influx of young families, perhaps 8-10 households between 2001 and 2010 which is a lot for an island of this size.

“These people are still here. In the lead up to 2001 we had quite a number of families leaving which was totally devastating. But we haven’t lost anyone like that since 2001.

“It arrested the decline. The population is similar now to what it was in 2001. But without the causeway it would have been down to 90-100 and there would be no young families on the island.”

When the island secondary school closed, the newly-opened causeway allowed Mr MacDonald to work for the next 12 years with the education department in Benbecula.

Higher standards of access demanded today

“It enabled me to stay here with my family. When the secondary school closed I would have had to move to Uist or search for work somewhere else. I could not have done what I did for 12 years without the causeway.”

Local councillor Donald Manford said the fear that Eriskay could suffer the same fate as other Hebridean islands in the past was reasonable.

“They are beautiful places to live, but standards of access are demanded to a much higher extent now than was historically the case. Privacy is prized, but so too is connectivity.”

He too saw the causeway halt the island’s downward spiral: “Without doubt it’s done that. You just need to pass through Eriskay today and see new houses taking shape. It has the look of a very sought-after place to be.”

Privacy is prized, but so too is connectivity.”

Councillor Donald Manford

Among the new generation of island residents are Julia and Stephen Campbell and their business partner Angus MacAlister. All in their 30s, they run the local pub, Am Politician, and are building new houses on the island.

Julia and Stephen, who married in April, moved away for work 13 years ago.

They returned in 2018 to help run the business, named after the SS Politician, the ship that inspired Whisky Galore.

“We would definitely never have come back if there was no causeway. I don’t think we would even have thought about coming back.”

The pub now opens seven days a week and draws customers from as far afield as North Uist and Berneray in the north to Barra in the south, as well as tourists.

“It’s good to be home. It’s more chilled out here”, said Julia. “I can’t really think of not being here now. There are more and more people of our age wanting to come home.

“There are also more coming back every summer now as it’s easier to get here. I don’t think they would have bothered before.”

New generation unaware of life before the causeway

The changing demographics means that, while the population was terminally ageing 20 years ago, there is now a growing number of young people unaware of Eriskay pre-causeway.

“A few of the girls who work here say the causeway is older than them and they don’t know a life without it”, said Julia.

Mary MacKinnon, secretary of Eriskay Community Council and chairwoman of the island hall committee, is another who returned to the island.

She and her husband have three daughters aged six to 22.

“I would definitely say the causeway has been an advantage to the island. A few people have moved back because we got it, ourselves included, and others want to live here now.

“There were also three babies born on the island last year and I hope that trend will continue.”

Another sign of change is Eriskay Historical Society’s plans for an exhibition centre.

It plans to convert the old school building, which closed in 2013 when primary children moved to Daliburgh, to feature Jacobites, whisky, the island’s maritime and crofting history, the famous Eriskay ponies and the causeway.

Society chairman John MacInnes said: “A development like this would not be possible without the causeway.

“In practical terms, it makes it easier for things like building materials to get here. But it has also opened up a whole market for people coming to the island.

Would a causeway be built today?

“Things have changed. A whole generation has grown up with the causeway with all services immediately available and now taken for granted.”

The Eriskay link was the latest in a series of transport projects in the Outer Hebrides that began in 1942.

In the 1990s causeways were built between Vatersay and Barra and Berneray to North Uist.

A bridge was also built to Scalpay, while a new car ferry linked Harris and North Uist as part of the ‘spinal route’.

Neil MacDonald believes Eriskay was fortunate the finance for came together around 1999-2000 and would not be available now.

The island’s MP Calum MacDonald, a Scottish Office minister for transport and the Highlands and Islands, gave the go ahead in 1999.

The project attracted £4.1 million from the government, £2.2 million from Western Isles Council and £500,000 from Highlands and Islands Enterprise.

The balance came from the European Objective 1 fund with Eriskay designated as a pilot area for the Initiative at the Edge project to help fragile areas tackle decline.

“In a sense we were lucky. A few years after that it probably wouldn’t have been built. A few things came together in terms of finance.”

“A couple of years later money became very tight. There is no chance in the world we would get it today.”