Most of us jump onto trains without a thought for how the railway got there in the first place.

The feats of engineering to conquer the terrain, the immense cost, both financial and human.

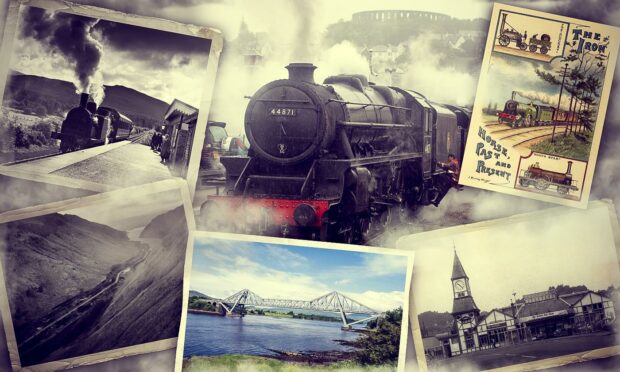

It’s easy to forget all that if you’re lucky enough to travel by train from Crianlarich to Oban, so stunning is the scenery.

But that line was also one of the most challenging railway engineering feats in the north, built by the Callander & Oban Railway Company, and the vision of one determined man who dedicated more than 40 years of his life to making it happen.

The original line covered the 70 miles from Callander in the Trossachs through beautiful but difficult terrain in Perthshire and Argyll to Oban on the west coast.

The line opened up Highland holidays

With it came the possibility of magical Highland holidays for dwellers of the Central Belt, and much more rapid connections to Edinburgh and Glasgow for west coast Highlanders- and their fish.

Oban man and railway enthusiast Ken MacIntyre drew much of his in-depth knowledge of the history of the line to John Thomas’s 1966 book, The Callander & Oban Railway.

He calls the C&O line a ‘small miracle’ and attributes its existence entirely to the dogged efforts of the company’s general manager, Glaswegian John Anderson.

“He needed every ounce of his ingenuity, energy and entrepreneurial drive to combat setbacks and financial struggles to see the C&O line to completion,” he said.

Anderson joined the C&O company when it was newly formed in 1865 and rose from the post of secretary to general manager, staying with the company for the next 42 years of his life, devoting himself solely to the realisation of the Oban line.

The line began in stages in 1866, and took 14 years to complete, overcoming numerous obstacles.

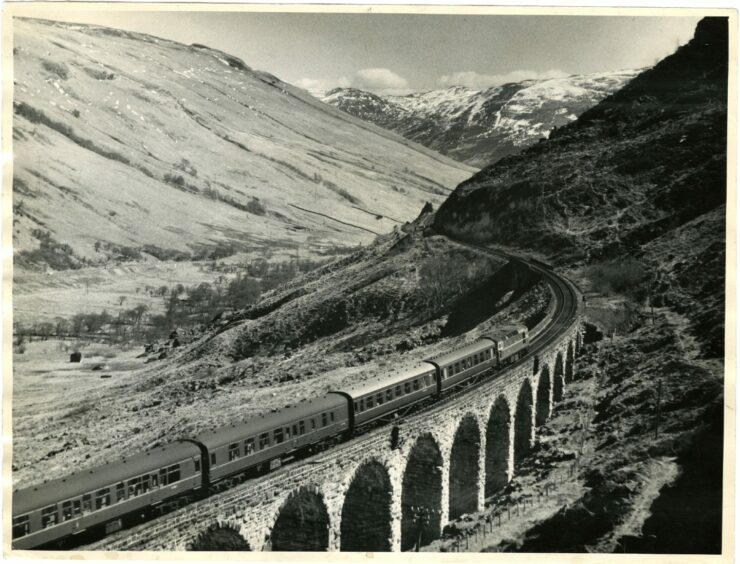

Ken said: “There was a chronic shortage of finance, difficult terrain, rivers, steep gradients and tight turns.

“Bridges and viaducts were necessary, such as the particularly challenging one at Glen Ogle.”

Sadly the Callander to Crianlarich stretch didn’t survive past 1965.

Large tracts of it are now for walking and cycling, including the Rob Roy Way.

A 27 mile branch line from Connel Ferry at the entrance to Loch Etive to Ballachulish on the shores of Loch Leven near Glencoe was added in 1903.

The Connel Bridge was built for C&O by Glasgow company Arrol to span Loch Etive.

At the time, it had a longer span than any other railway bridge in Britain except the Forth Bridge.

Although the branch line opened up remote areas, it was never a commercial success.

Ken’s father Kenneth drove the last ever Ballachulish train in 1966.

But the 40 miles from Crianlarich to Oban remain open today, with travellers from the central belt changing at Crianlarich to get to Fort William and Mallaig.

This treasured section is known as one of the most beautiful train journeys in the world.

Railways don’t just happen

Railways don’t just happen, and as Ken reminds us, the C&O very nearly didn’t.

“The original promoters of a line to Oban – then a fishing port and holiday town with a population of 3,000 – approached several Scottish railway companies.

“The largest, the Caledonian Railway, declined but its smaller rival the Scottish Central Railway offered its westernmost outpost at Callander plus an investment of £200,000 towards the £600,000 cost — £77 million in today’s terms.”

Scottish Central was then taken over by the Caledonian, and the line might have foundered at this point.

“There was opposition to the C&O project among Caledonian shareholders who were reluctant to invest in a line running through sparsely populated countryside linking towns of a total population of 4,000.”

But it survived, albeit with a somewhat challenging relationship between the Caledonian and the C&O.

The Caledonian was a major shareholder, operating the trains, stations, track and signalling and employing the staff.

Money raised from beneficiaries of the line

John Anderson’s work didn’t stop at construction.

He worked tirelessly to promote and raise money for the C&O, using fairly blunt tactics to persuade people who stood to benefit from the line to buy shares in the enterprise.

Ken quotes an example of a letter to an hotelier when he was appealing for funds for the final section to Oban in 1877:

“I would like to see a respectable sum opposite your name and I must ask you to let me put down your subscription for £300. The money will not all be required at once, and I feel certain that you will be the first to feel the advantage from the extension, and you will soon recoup yourself the amount I have named. Be good enough to let me have an answer, and a favourable one, by Saturday.”

Faced with that verbal strong-arm, the hotelier took twenty shares at £10 each, the equivalent of £24,000 today.

Bit by bit the line took shape

Services to Killin started in 1870 with two trains a day in each direction, and connecting coaches to Oban and Fort William.

Anderson wasn’t about to let a matter of dangerous rock fall stop the trains heading along the Pass of Brander at Loch Awe.

There had been a derailment due to fallen rocks, so Anderson devised a unique and ingenious solution, known as ‘Anderson’s Piano’.

Ken said: “In 1882, a system of semaphore signals linked to a wire screen was erected along the track, which eventually covered 17 signals in a 4 ½ mile stretch, a system that continues to this day.

“In the event of a boulder crashing through the wire, the signal is automatically set to danger to warn the train driver.

“The Pass of Brander Stone Signals are also known as Anderson’s Piano because of the humming noise made by the wind in the wires.

“The system has been very successful with just three derailments in 140 years, in 1946, 1997 and more recently in 2010, remarkable considering that there must have been hundreds of thousands of trains in that time.”

Dalmally was reached in 1877 and in 1880 the section to Oban was finally complete, to a great fanfare and banquet at the newly built station.

John Anderson didn’t rest there.

He worked tirelessly to devise tours and day excursions combining rail, coach and steamer travel.

Ken said: “Of 58 tours promoted by the Caledonian in 1911, more than forty featured the C&O.

“Loch trips were especially popular, with Loch Earn, Loch Tay, Loch Awe and Loch Etive accessible from the line.”

Ken’s passion for the C&O is intensely personal.

His father Kenneth, pictured above, worked on the railway for almost half a century, first as an engine cleaner, then fireman and driver.

One of Ken’s earliest memories is aboard the Evening Citizen Television Train, where he’s snapped in this photo from September 24 1956 when the TV train visited Oban for the first time to bring the joys of television to its inhabitants.

He is the boy in front of the man with the cap, just shy of his fourth birthday.

“I remember seeing ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy Archie Andrews, who were very popular at the time with their radio show, Educating Archie, which introduced many popular artists including Tony Hancock, Beryl Reid, Dick Emery, Harry Secombe, Bruce Forsyth, Max Bygraves and Julie Andrews.

“I think also we saw singer Kathie Kay who was featured on Billy Cotton’s radio and television show.”

The 1880 Oban station and its surroundings was Ken’s happy childhood playground.

“Next to the station was a small park with an outdoor draughts set, where I played happily many times and I remember the back of the station cafe with the smell of beer from the crates of empty bottles.”

During the 1970s and 80s the station declined in use and was eventually demolished in 1987.

Luckily the only C&O building left in Oban, the listed Victorian tenement in Alma Crescent where Ken grew up, still remains, with the flats modernised and now in private ownership.

You might enjoy:

Beyond the Beeching cuts: Would branch lines revival boost north east communities?

Trip back in time: Did you journey aboard the British Rail TV Train?