In more ways than one, the A9 has been overdue an upgrade for an absurdly long time.

Take a trip through its history and you’ll find a route that has been regularly dismissed, forgotten about and fed on scraps for years.

At 273 miles it is Scotland’s longest road, but to most people in the north it doesn’t feel like it’s ever been given a fair shake.

The prolonged delays to the dualling campaign have made headlines recently but sadly, it’s far from the only setback we’ve seen down the years.

Here is the story so far.

Before it was known as the A9

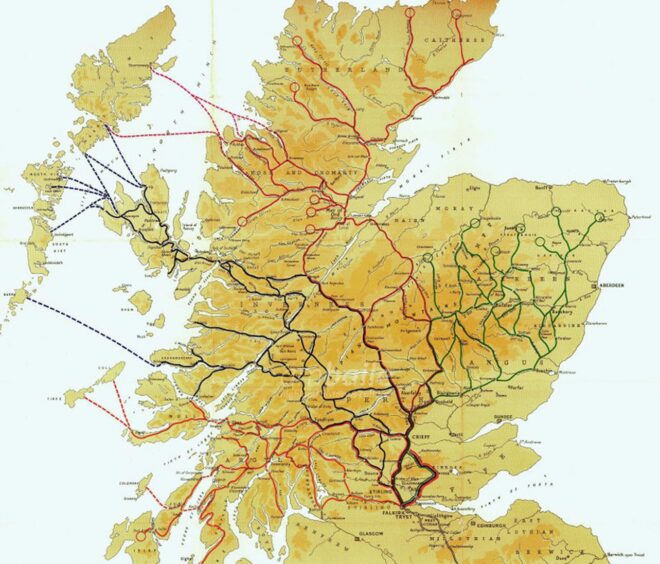

Looking at a map of Scotland’s drove roads, you can see much of the shape of the modern A9.

These tracks were the main pathways for people travelling between the Highlands and the Lowlands.

And they offer a hint that this corridor has been in use for more than 500 years.

The first big project on the route was in the 1720s.

The construction of General Wade’s military roads from Dunkeld to Inverness took place between 1728 and 1730, primarily to increase resistance to the Jacobite uprising.

By the early 1800s, the need to upgrade transport across the north was becoming clear.

The Commission for Highlands Road and Bridges was set up by parliament and Thomas Telford was put in charge of the work.

During a 20-year span, Telford transformed swathes of rugged wilderness into 870 miles of roads.

1922: Becoming the A9

The rise of the motor car in the 1920s meant major improvements were needed, and needed quickly.

The route between Edinburgh, Stirling and Inverness was officially designated a trunk road and given its now familiar title in 1922.

Construction on the stretch between Inverness and Blair Atholl followed to allow two-way traffic.

This was a mammoth piece of work that required widening, bypassing or replacing numerous bridges.

But as car ownership increased steadily, so too did the pressure on the north’s main road.

As a motorway network was constructed to link the central belt, plans to upgrade the A9 between Inverness and Perth were finally getting the oxygen they deserved.

1970-1986: The construction years

Things took a huge leap forward in 1970.

The publication of a white paper identified the A9 as a road in serious need of investment.

May 1972: A huge programme of works was announced by the UK government, reconstructing the full road to modern standards and providing several bypasses.

However, even at this stage questions were raised about why it wasn’t being dualled.

After being told it wouldn’t be, Labour MP Gavin Strang said it “represents the most short-sighted, irresponsible and stupid decision yet taken by the present government in Scotland”.

According to George Younger, parliament under-secretary for Scotland, it wasn’t necessary to dual the road.

He responded: “What this road needs above everything else is to be straightened and widened and to have its severe gradients removed.”

Some dual carriageways were built during the reconstruction, along stretches thought to be the most congested.

August 1975: Construction of the Longman roundabout is complete. However much we think we hate its traffic jams now, it was an important piece of work.

June 1976-September 1981: A number of significant bypasses are built during a five-year frenzy of construction.

Dalwhinnie, Dunkeld, Birnam, Luncarty, Aviemore and Pitlochry get one each for a combined cost of £37m.

Along the way, numerous improvement projects are carried out.

August 1982: The Kessock Bridge opens at a cost of £35m, one of the major construction milestones of the plan.

Further north, the Cromarty Bridge set the pace when it opened in 1979. The Dornoch Bridge would ultimately follow in 1991.

1989-1993: The ‘killer A9’

October 1989: Five people are killed in an accident near Dunkeld.

The fallout prompts comments from a local councillor that accidents are being caused by “stupid drivers” driving at high speeds and the Daily Record refers to the road as “the killer A9” for the first time.

A total of 21 people are killed in a nine-month stretch and the tag sticks.

January 1990: Tayside North MP Bill Walker calls for signs displaying the number of accidents and people killed to be erected at the roadside.

He said: “Such signs are already in place on the English section of the A68 road south of Coldstream.

“They definitely act as a deterrent.”

Mr Walker makes a fresh call to dual the A9 in February 1991 after another fatal accident near Calvine.

June 1993: Introducing a third lane to the A9 – for alternate use between the two flows of traffic – is floated as an alternative solution to dualling by the Scotland Office.

However, the idea is quickly dubbed “the kamikaze lane”.

The Scottish Accident Prevention Council calls the prospect a “backwards step”.

The idea is quietly shelved, although individual overtaking lanes are introduced at Moy, Carrbridge, Kincraig and Newtonmore in the 2000s.

1999-2006: A new hope on the A9 timeline

May 1999: The Scottish Parliament opens to huge fanfare. There is a sense of optimism that devolution will offer greater opportunities to fix our nation’s problems.

Your assessment of how that has worked out tends to depend on which side of the constitutional divide you are on.

But as far as the A9 is concerned, no miles of dual carriageway between Perth and Inverness are added between 1999 and 2011.

September 2006: The Scottish Conservatives launch a fresh campaign to fully dual the A9 ahead of the following year’s Holyrood election.

That summer, five people die on the road within a month over the summer.

Between 1999 and 2006, more than 80 people are killed on the route.

The Scottish Government, at this point a coalition between Labour and the Lib Dems since 1999, repeatedly resists claims to dual the road.

It argued that the quoted £600m cost was too high. At that point, most of the road had an accident rate below the national average.

Instead it focuses on improvements at accident blackspots and upgrading junctions at Ballinluig and Bankfoot.

2008-the present: The promise

August 2008: First Minister Alex Salmond promises to dual the entire stretch of the A9 between Perth and Inverness during a historic cabinet meeting held in the Highland capital.

The strategic transport projects review later that year confirms the plan and lists the price at nearly £3bn.

December 2011: Scottish Ministers confirm a commitment to complete the dualling project by 2025.

October 2014: Average speed cameras are introduced on the A9 between Inverness and Dunblane.

The scheme attracts a lot of criticism.

But ultimately, the rollout leads to a drop in speeding, accidents and deaths along the route.

December 2022: After a period of time where the number of deaths had remained relatively low, fresh pressure is heaped on the Scottish Government after 13 people are killed in 2022.

A slow rate of progress and spiralling construction costs had already made the 2025 target date look unlikely.

And that was even before the Covid pandemic caused further disruption.

February 2023: Transport minister Jenny Gilruth announces that the 2025 is “simply no longer achievable”.