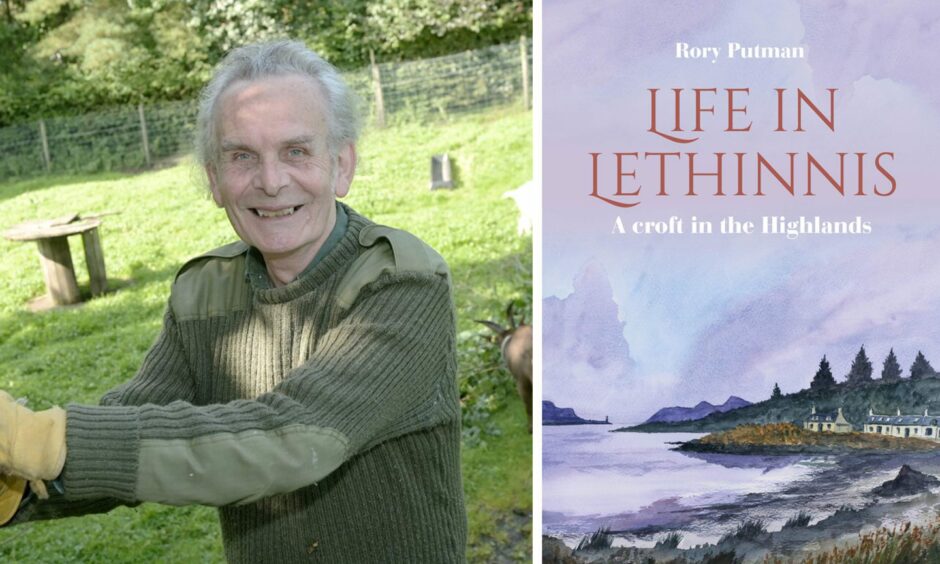

Thirty years ago, Rory Putman and his late wife Morag made the break from the south of England to set up home and a small holding on a croft on a West Highland peninsula.

Rory’s new published memoir of the time captures an era now lost in all but a few pockets of the Highlands, life at a slower, kinder pace.

To protect the innocent, Rory is keeping the exact location strictly secret, changing the names of all the places and the majority of the people concerned.

All he will say is that ‘Lethinnis’ is a peninsula, and the village of ‘Lochuisge’ is 15 miles from Fort William, a ferry ride and then a single-track car ride of 42 miles.

Rory and Morag both had strong Scottish roots and were unhappy with life in the materialistic and over-populated south where Rory was a researcher/lecturer at the University of Southampton.

They wanted to immerse themselves in life as it was lived 50 years before, with people born and bred in the same village all their lives, Gaelic speaking, and with a strong sense of community.

Tremendous sense of community as a crofter

“I loved staying where we stayed because there was still that tremendous sense of community,” he says. “I’ve been back to the village since we left and it’s gone. Completely gone. There only one person left who is native.

“All the remainders are incomers, as indeed I was.

“But I wanted to experience that traditional way of life, not change it.”

It took the Putmans five years, many coincidences and possibly a few drams to find the right place.

‘Lochuisge’ only had one incomer —’Alastair the Post’, and he’d only lived there 50 years— and two holiday homes.

It had 22 inhabitants and the nearest village was 12 miles away.

The Putmans bought the estate’s former lodge house, itself an old inn with quite a history.

It had survived the reprisals against the Jacobites at the end of the 1745 uprising, probably because it was an independent freehold, not in feu to a Catholic landlord.

The couple got on with fixing up their home and stocking their small holding, and found that despite a few raised eyebrows at some of their methods, they were readily accepted by the community.

Rory said: “We were the youngest by at least 20 years, everyone else was over 60. The village was in a sense dying anyway, and I think people thought if we don’t welcome incomers the community is going to die on its feet.”

Much loved village characters enhanced Rory’s life

Rory treasures the memories of the characters he met during his time in ‘Lethinnis’, from the former Laird partial to a dram who during a visit “peered at her half-full tumbler suspiciously before barking: ‘Young man. What is wrong with the top half of the glass?'”

Rory’s fishing companion ‘Donnie’ is an endearing character, so broken by various accidents that his left side was virtually useless and his speech difficult and slurred.

But when it came to fishing, ‘Donnie’ always seemed to know where the best mackerel runs were.

“His so-called disabilities counted for nothing in the place of extended family, and he was much loved for who he was — and his irrepressible sense of humour”, Rory writes.

Also engraved in Rory’s affectionate memory banks are the key people of the village, those who ran the Post Office.

“Alastair, Seonaid and Kirstie the post. They really held the village together, they were the glue that kept the rest of the rather scattered community together, because we all spent time at the post office.”

Many was the spontaneous ceilidh to be had when people met at the post office.

You had to set aside at least an hour to purchase even a stamp.

Rory writes: ” Tea was drunk and news was exchanged even if you have been there only the previous day; cattle prices at the local auction market would be discussed and closely dissected, or the start of some other unfortunate neighbour’s stock-fences or his haemorrhoids. ”

A full-scale ceilidh would develop spontaneously

Somebody might call by and remember his accordion in the back of the van, and a full-scale ceilidh would develop with singing and drams lasting well into the night.

“Then there was ‘Dolly Tom’, who first introduced me to the house and how lived just down the road from us, a spinster in service at the Big House,” Rory said.

It was ‘Dolly’ who brought it home to him just how God-fearing West Coast communities could be.

One year it had rained non-stop and a dry window emerged in which to cut the hay, vital to feed the household’s cattle throughout the winter.

But it fell on the Sabbath.

Rory writes: “Dolly and her family sat in the house and watched the hours turn by on the family clock.

Respect for ‘God’s time’

“Eventually midnight struck to mark the end of the Sabbath, and all were galvanised to rush out into the moonlight and start to gather the hay—to be stopped short in their tracks when one family member observed that while it might be midnight in this new-fangled summer time, there was yet an hour to wait before it would be truly midnight by ‘God’s time’.

“And wait they did because no one really had developed any respect for this innovation of daylight-saving time, or as it remains known in these parts, ‘daft time’.”

Sadly Morag died during the Putman’s tenure in Lethinnis, but thanks to the kindness of friends, Rory was able to find love again.

“Cathy was with me for the last few years.

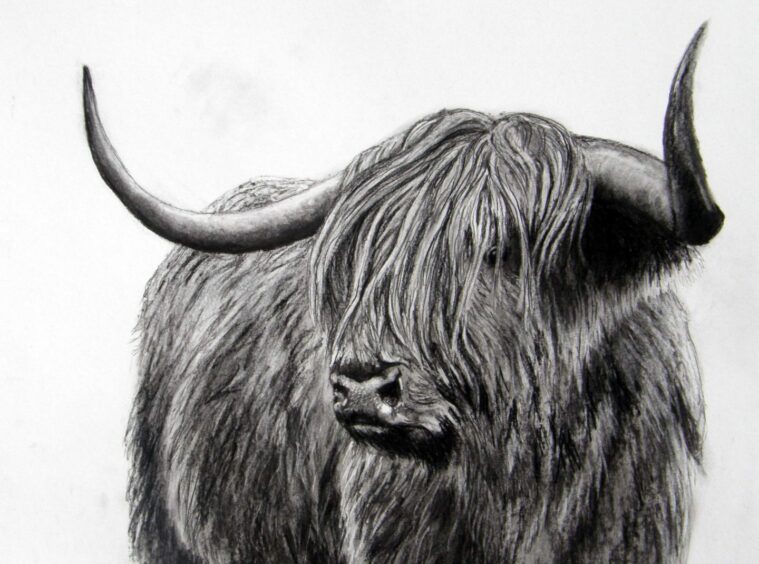

“She was a wildlife artist and illustrator. We met because she had commissioned by mutual friends to paint one of my dogs as a thank you for some favours that I had done them over the years.

“When she’d finished the painting, much to their surprise, because she lived in Peterborough at the time, she decided she would come up and deliver it in person, and she never went away again.”

Devastatingly, Cathy died two years ago.

Cathy made beautiful illustrations for Rory’s book

Her legacy is the beautiful illustrations she did for Rory’s book, although she didn’t live to see the book published.

Rory hopes interest in his memoir Life in Lethinnis will be sufficient for him to write a sequel, for which Cathy has left plenty more illustrations.

He looks back with intense love and affection upon his life in ‘Lethinnis’, but knew when the right time came to leave, in 2010.

He now crofts near Banavie, near Fort William.

He said: “With, increasingly, the older, native residents of the village dying or moving away to sheltered accommodation and with a change of Laird on the big estate, the village had lost its former character and sense of community.

“It was being ‘overtaken’ by retired civil servants or their like who wanted to bring the Home Counties with them.

“The atmosphere had changed.

“When I left people said aren’t you going to miss it and the answer was very simple, I already miss what was there, I’m not going to miss what it is now. ”

Life in Lethinnis is published by Whittles and available here.

More like this:

Tilleys, Rayburns and dipping ink: Memories of a 1950s childhood in Sutherland

Treasured way of life: Do you remember mobile shops in the Highlands?

Conversation