For most people, venison is seen as an exclusive meat — something to have on a special occasion or from a nice restaurant.

Even though Scotland is overrun with deer.

Cairngorms Connect is a partnership of neighboring land managers committed to a long-term, landscape-scale vision for ecological restoration.

A big part of this includes reducing deer numbers across the 600 square kilometer area — three times the size of Glasgow.

And as a result, they sell sustainable venison to the local community at a reasonable price, proving the meat can be accessible to more people.

We caught up with Cairngorms Connect to find out how the venison project is going so far…

Cairngorms Connect Venison Project

Since 2014, RSPB Scotland, Wildland, NatureScot and Forestry Land Scotland have worked together on the Cairngorms Connect.

Sydney Henderson, communications and involvement manager, explained the venison project was launched as a “by-product” of deer management.

She stressed it’s not why they manage the deer, but it’s a way to make the meat more accessible and sustainable, and a way to talk about why reducing the numbers is so important.

“I think venison is seen as quite an exclusive or special occasion meat,” she said. “Whereas actually it should be much more accessible for local people in the Cairngorms and across Scotland because there is this natural resource.

“We can benefit nature and climate, and provide local, sustainable meat to people as well.”

The venison project started quite small, but now they’ve partnered with several local businesses and butchers and even launched a new delivery and collection service in November last year.

Sydney said the new service was so popular it sold out in 48 hours, and that there’s a huge demand for the venison locally.

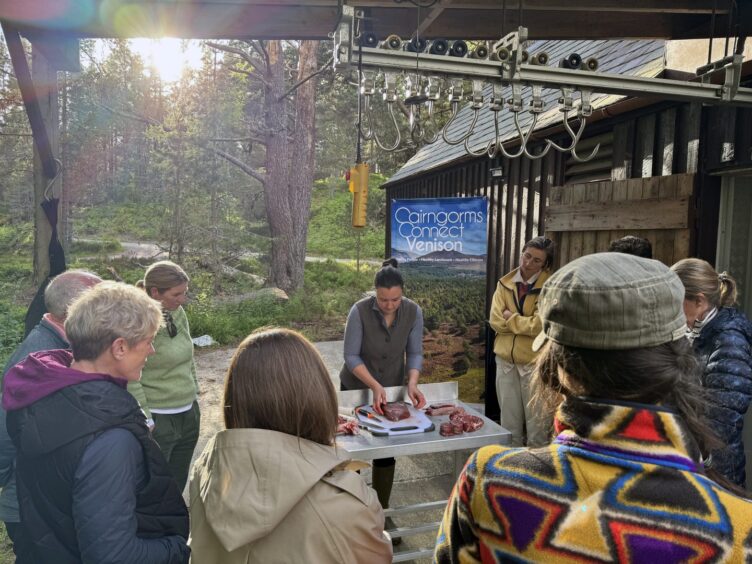

The group has also run events to share the story of the Cairngorms Connect venison, including venison butchery and cooking masterclasses.

And around 800 people attend their annual Hill to Grill event, telling the story about deer management.

“I think it shows there is such huge interest in this,” she added. “We’re excited to be starting these conversations locally around accessing affordable, sustainable, environmentally friendly meat.

“I’d like to imagine we get to a point where it’s less of a special occasion meat, and it provides an opportunity for people to connect with the place that they live through the food that they eat, which feels quite exciting.”

Why do deer numbers need to be controlled?

Jack Ward has spent most of his career monitoring wild deer populations, before joining the Cairngorms Connect as a stalker in 2019.

He explained that deer management is the main method they have of conservation. Without controlling deer numbers planting trees and repairing peatland “doesn’t really work” because of the high grazing pressure.

There are no predators like lynx or wolves to manage the deer, so Jack and the team act as the predators. And even when they’re not shooting the animals, their presence can help them move around more naturally.

“When deer know there are no predators in that landscape, they become quite lazy,” he explained.

“As you would if you’re not under any pressure, you don’t move necessarily. But that can lead to quite high impact through trampling and browsing and grazing, and in a small area the impact gets so great there’s nothing left.

“So then the deer have to move and have the same impact somewhere else. The ground that they’ve impacted then takes a long time to recover because it’s been hit so heavily.

“Whereas if there’s a predator in the landscape, prey species such as deer, are far more active, because if you just sit down in a group, a predator will find you.”

‘Deer engineer the woodlands’

Jack has seen the deer change their behaviour since they’ve been involved in the project.

He says they don’t just sit in areas anymore, but they’re still having an impact on the landscape — which is what they actually want.

The stalker added: “It’s why we don’t use fencing, but they have to behave naturally. And they only behave naturally in the presence of a predator which manages them, and in our case, that’s us.

“The deer do a really good job, they engineer the woodlands just like people say about beavers.

“It’s just they can over-engineer the woodland when there’s too many of them.”

Cairngorms Connect helping future deer

Jack explained when there are too many deer, they eat a lot and erode the ground, meaning there’s less for them to eat and there’s less shelter and cover to protect them too.

And this can mean winter, which is a harsh time for most wildlife, can be even tougher for the deer standing on freezing open hillsides.

But in the project area, they have good forests and regenerating forests, the landscape is healthier and those deer have a lot more shelter and food.

“What we see as a result of deer having a mixed healthy diet in woodland cover, where they’re not having to burn all the energy just to stay alive, is that they achieve higher weights.

“So they generally grow slightly quicker. A one-year-old deer that has survived it’s life out on the hillside will be significantly lighter than a one-year-old deer that has lived it’s life in a woodland.

“This is because the one on the hill has had to use so much more energy just to survive, whereas the one in the woodland has had quite a comfortable time of it and has been able to pile that energy into growth.”

When Jack and his team shoot a deer, they inspect it and can see how much fat is on them — which he says is a good indicator for their health.

Scottish wild venison can be sustainable

Normally by the end of winter, deer have used all their resources to stay alive. But in their project area they get deer in February and March that still have quite a bit of fat around their organs, meaning they aren’t at their survival limits.

And when they’ve got a higher welfare, maintaining weight and they’ve got shelter, that means they will breed more.

“We want the healthy deer,” he added. “But also it means that there’s a whole level of sustainability in there. When the deer are healthy in this landscape, they produce more deer, so my job will constantly be needed.

“Because we’re producing more venison now at a faster rate than they were before it means we’ve got that constant supply of food coming through, and that’s the kind of true sustainability of food — that the harvest you take doesn’t outweigh the rate that it can recuperate itself.

“We will eventually strike that balance, but in a changing landscape that’s always going to be dynamic.”

Cairngorms Connect venison shows it can be accessible

The Cairngorms Connect venison is all sold locally, and according to Jack has quite a few health benefits.

He explained it’s one of the highest protein red meats, and it’s very high in omega three and six.

While people can have venison anywhere in the UK, they don’t normally know where it comes from — meaning it could have travelled from quite a distance.

New Zealand is one of the biggest exporters of the meat, meaning venison is being shipped thousands of miles to end up on plates in Scotland where there’s an overpopulation of deer.

Meanwhile, the Cairngorms Connect venison has “rock bottom” food miles because it is kept local and not sold to game dealers.

For example the venison sold in Aviemore’s The Old Bridge Inn could have come from Glenmore or Abernethy, meaning it’s travelled 15 miles at most.

And by cutting out the middleman, Cairngorms Connect can keep the prices low selling a really affordable premium product while still telling their story.

He finished: “The venison project wasn’t set up so we could produce venison and sell it, which sounds a bit strange. We’re producing venison anyway, because the key aim of what we’re doing is managing the deer, and therefore we produce venison.

“The aim of the venison project is to reach out to people, make people realise that venison is healthy and sustainable, and get people to be involved as well. It’s not about making money.

“And the money we make goes back into the venison project, and anything surplus from the venison project goes into community projects.”

If you would like to find out more about the project, or where to buy the venison, then click here.

Conversation