A Highland community has commemorated its wartime heritage with a new exhibition.

Kinlochleven played host during World War I to prisoners of war and political prisoner camps.

The village marked the centenary of their opening at the weekend with theatrical performances and new public archive material explaining the lasting legacy of the internment facilities.

More than 200 people attended the event on Saturday and many returned yesterday, with around 100 visiting the village’s Leven Centre and Kinlochleven High School.

Local historian Avril Watt said the 100th anniversary event was aimed at introducing younger generations to the area’s wartime past – as well as “compassionately” exploring what lead the German soldiers to a remote part of the Highlands.

She said: “We were very pleased with how it went. More than 200 people attended on Saturday and many came back today (Sunday).

“Everybody seemed to take something from the event, the plays were very good and it was a success.”

An exhibition explaining the camps will now remain in place in the Leven Center until December.

The exhibition included photographs from the time as well as a scale replica of a Nissen hut.

Visitors were also given the chance to take part in a taste test based on recipes from the rationing era.

The inmates left a lasting legacy in south Lochaber, being put to work building the road on the south side of Loch Leven from Glencoe to Kinlochleven, as well as laying the pipeline from the Blackwater Dam to Loch Eilde Mor.

Trusted interns also worked in the village and helped maintain villagers’ properties.

And, after one flood at the River Leven camp, some were even offered shelter in local people’s homes.

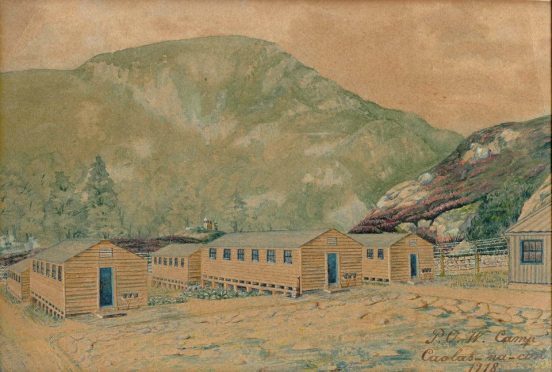

Although overgrown in places, some of the base pillars, concrete bases and retaining walls of this camp are still visible. There are also remains of the conscientious objectors internment camp at Caolasnacon.

Ms Watt said: “I became interested in the German prisoner of war camps many years ago as I was fascinated by how the German prisoners were accepted into the community as sons of German parents, who had been conscripted into the war – just like our own sons, fathers, uncles and cousins were. The German prisoners were looked after as our own.”

She added that many British prisoners of war were not as lucky and suffered terrible conditions.