A new disease comes in from abroad, spreads like wildfire and within weeks two-thirds of the population are dead.

Not the latest doomsday scenario for Covid-19, but something which really happened in Fair Isle in 1700.

Not only that, but when a successful vaccine was finally developed, anti-vaxxers also kicked into action a couple of centuries later.

Smallpox was the dreaded disease.

It had been brought to Shetland that summer by a young man returning home, and the islanders had no immunity to it.

The impact on Fair Isle was that no-one was left to manage the island’s fishing boats.

The disease spread to the other islands and at length, “The dead in everie corner were so many that the living and whole could scarsely be able to bury them,” reported the minister of Tingwall in December.

Historian Brian Smith, archivist at the Shetland Museum and Archives, has delved deeply into the smallpox epidemics in Shetland.

His research, available in the Shetland Archives, shows they cropped up regularly at clockwork at 20 year intervals, with three more catastrophes to come, in 1720, 1740 and 1760.

Elsewhere it was common for smallpox to attack infants and children, but in Shetland it took out the breadwinners.

This made Shetland at least unusual, perhaps unique, Mr Smith says.

“Shetlanders henceforth referred to the 1700 visitation as the ‘Mortal Pox’ and in later years old people calculated their ages from this or that year before or after it.”

There was no solution at the time.

“For the Presbytery the catastrophe was ‘God’s just judgement by reason of our sin’.

“All the minister of Tingwall could offer was ‘fasting and prayer, that the Lord’s wrath may be appeased’.

“The bodies piled up; the survivors, pock-marked, sometimes blind, waited for the next visitation on their children and their children’s children.”

Fortunately, in 1730 an unusual soul would make his appearance in Shetland, and among many other activities and creations, would come up with an inoculation process and save the lives of thousands of his compatriots.

John – known as Johnnie or Johnie- Williamson was born into a tenant-farmer family in Hamnavoe, north-west Shetland.

Mr Smith thinks he caught small pox in the epidemic of 1740, at a time of famine and deep cold in northern Europe – perfect conditions for epidemics.

Hundreds of men, women and children died, helped on by starvation rather than purely the disease itself.

“In Lerwick the Kirk Session had to extend the kirkyard by 50 feet, and announced restrictions on paupers’ rights to coffins and winding sheets.” Mr Smith writes.

“In the smallish island of Fetlar 120 people died – more than in 1700.

“Later there was a tradition that the Fetlar kirkyard was filled in every corner, except in the spot reserved for suicides and drowned men.

“To make things worse, the frost was so severe in the winter of 1740-41 that for six weeks the Fetlar people could not dig the earth to bury their dead.

“Years later, a factor in Unst reckoned that about a third of the population of the island died in what he called the ‘very Mortal Small Pox’ of that winter. ‘I think the Tenants did not increase before 1749 or thereby’, he calculated.”

Johnnie Williamson took over the lease of the Hamanvoe farm from his father from one Thomas Gifford.

He was obliged to keep ‘half a six oar boat to the sea’ in a compulsory fishing arrangement, and he appeared to prosper reasonably well.

He married Christian Nicolson, and five children appeared between 1753 and 1763. Some died from the next small pox strike in 1760.

This time there were rumours of a solution, and Johnnie was taking note.

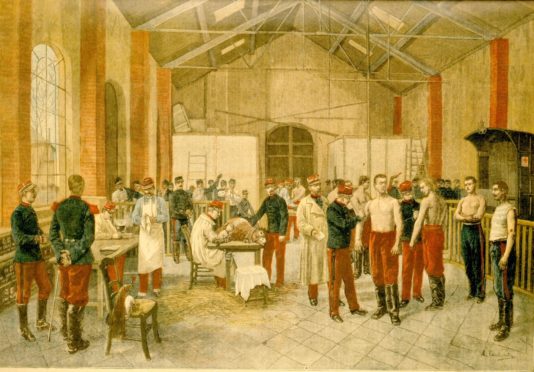

As far back as 1701, a Chinese method of variolation or inoculation had been described to the Royal Society, whereby smallpox was introduced into men and women to give them a mild version of the disease in order to provide immunity.

For the next two decades, the subject would be all talk and no action, while all doctors could do was isolate victims, and either sweat them or give them fresh air.

In 1721 Aberdonian Dr Charles Maitland successfully inoculated an infant in London, before going on to inoculate condemned prisoners in Newgate with equal success.

But there were differing reactions from the public – the rich saw it as a panacea, while others feared it as brutal and irreligious.

In 1758, a few cases of smallpox had started to appear in Shetland, and locals appealed to Shetland doctor William Edmonston, practicing in Leith, for help.

He described a method of inoculation involving making a small cut in the arm or leg and introducing ‘poxy matter’ (matter from smallpox sores) on a tiny piece of cotton into the wound and keeping it there for up to three days.

But it was a treatment for rich people, and not more than a dozen people benefited, so the 1760 epidemic was as devastating as the others.

By 1769 William Edmonston’s nephew Laurence was practising in Lerwick, and used the method to inoculate several hundred people when a minor epidemic began that year.

Meanwhile Johnnie Williamson had not only been farming and fishing, he was proving himself in a whole series of occupations – tailor, joiner, clock and watch mender, blacksmith and physician.

He had what a visiting minister in 1774 described as a ‘remarkable mechanical turn, especially for imitation’.

He had particularly impressed the minister with his exact replica in miniature of a bleaching mill, prompting the minister to describe him as a genius ‘under a great disadvantage, never having it in his power to improve his genius as he might elsewhere’.

Dabbling in inoculation

Johnnie was dabbling in inoculation, coming up with a plan to make a milder form of the disease to introduce into the populace.

Brian Smith said : “Many inoculators used their inoculating matter right away, but Johnnie Williamson had come up with the idea – another of his notions – that it would be less dangerous if he prepared it carefully before use.

“He dried it in peat smoke, and then buried it with camphor. Camphor was anti-bacterial, and would have prevented the matter from putrefying.

“A local tradition suggests that he put the pus between sheets of glass before burying it.

“He seems to have collected large amounts of matter, because there is evidence that on some occasions he buried it for seven or eight years, and thus did without the benefit of it for long periods.”

He invented his own knife for the incision, avoiding drawing blood, and inserted a tiny amount of the matter. Then he would slap a cabbage leaf over the wound as a form of plaster.

Johnnie ‘Notions’

By this time he was known as Johnnie Notions.

According to oral tradition, it came from his landlord Thomas Gifford.

Mr Smith relates: “Williamson was in Gifford’s house, presumably on business, and the landlord asked him to rid his house of ‘checks’, small noisy wood-boring beetles.

“Williamson looked behind the clock and cleared away a mass of creepy crawlies.

“‘You hear no more checks now,’ he said.

“Gifford replied, fatuously, ‘What a notions!’

“The story is peculiar, but it was recorded in 1889 from Williamson’s own great grand-daughter.”

If people were tempted to deride Johnnie Notions, they had to think twice.

Never lost a patient

The minister of Mid and South Yell reported that he had inoculated several thousand people without losing a single patient.

We don’t know enough about the secondary infections from his treatment.

Mr Smith said: “Several Shetlanders were known to be blinded after inoculation, but there can be no doubt at all that John Williamson and his fellow inoculators saved far, far more lives than they blighted or lost.

“It can be stated with certainty that Williamson and his colleagues altered Shetland’s demographic history.

“When inoculation came on the scene, the population could grow faster and the economy could burgeon.”

Johnie Notions seems to have worked as a travelling inoculator, charging around 4 shillings sterling a time.

It’s unclear when he died, but accounts between himself and Gifford stopped in 1796-also the year of Edward Jenner’s discovery of vaccination using cow pox.

In Shetland the path of mass vaccination didn’t always run smooth.

In the 18th century islanders were keen to take up inoculation in contrast to the populations of the central belt, Aberdeen and further north where there was massive opposition.

Mr Smith says: “People railed against doctors who, they reckoned, were tempting faith, and reason by using dangerous smallpox matter.

“But Shetlanders had had a worse experience of smallpox than almost anyone else.

“Where in Glasgow it was a disease of bairns, often poor bairns, in Shetland it had carried away young and old, rich and poor, perhaps a sixth of the population on each occasion.”

Vaccine arrives

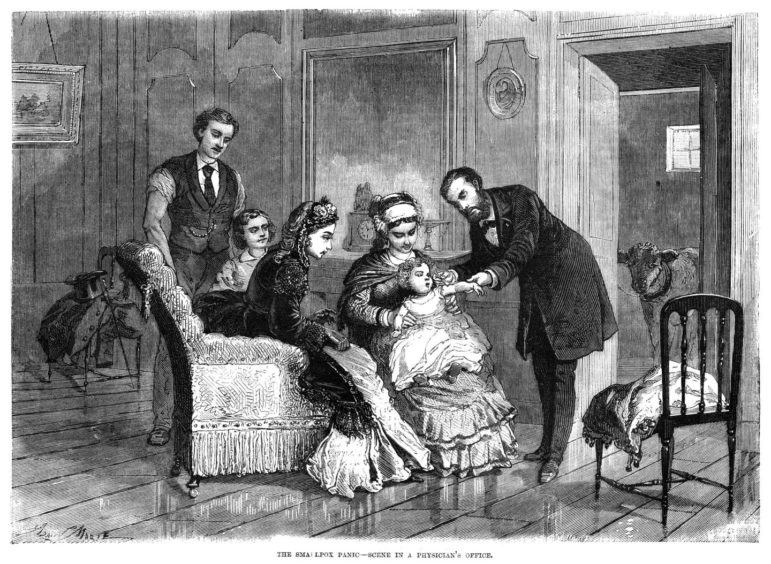

The cowpox vaccine arrived in Shetland in 1804, just as smallpox reappeared.

Shetlanders took up the vaccine, and a potential epidemic was averted.

But cowboy vaccinators also appeared on the scene, with one using scabies matter instead of cowpox.

Some of his victims caught smallpox and died, throwing vaccination into disrepute.

Islanders got a fright in 1830 when there was another epidemic, but grew complacent again when the disease declined over the next three decades.

Mr Smith said: “On the eve of the Vaccination (Scotland) Act of 1863 it was thought a third of the population was unvaccinated. After the Act, it was general throughout the islands by the 1870s.”

Fifty years later, in the 1920s, the population was again unvaccinated.

“The size of Shetland’s unvaccinated population in the twenties and thirties proves that Shetlanders thought very strongly about the subject.

“No-one seems to have written down precisely why he or she objected, but I suspect that Shetland’s anti-vaccination feeling was an amalgam of repulsion from cowpox, perhaps some religious scruple, and most important, attentiveness to individuals’, particularly children’s rights.”

No memorial

Mr Smith laments there is no memorial to Johnnie Notions and his like.

He said: “I sometimes have a feeling that Shetlanders today regard Johnnie Williamson as part of ‘heritage’, rather than as a nimble-minded eighteenth century Shetlander who was on the side of life rather than death.

“There is still no sensible memorial to him or to his fellow inoculators and vaccinators in Shetland.

“Johnnie Notions and his colleagues changed things.

“They turned the tide of history in their native islands; they deserve our respect and study and love.”

Smallpox killed around 300 million people worldwide in the 20th century. It was eradicated by 1979 entirely thanks to global immunisation.

See more like this: