The public in Wick thought little about the sight of a bespectacled middle-aged chap setting up his easel and starting to work assiduously on a new painting as they went about their daily business in 1936.

This Englishman in their midst was an unfussy character, a fellow approaching 50 with no trace of pretension who later remarked: “I am not an artist. I am a man who paints.”

As the hours passed, he meticulously chronicled the comings and goings of the residents using his trademark style.

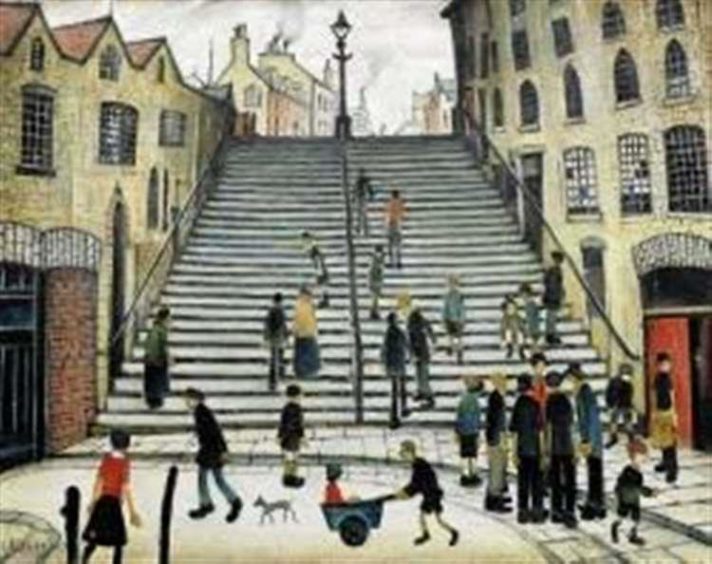

His efforts led to the creation of Steps at Wick, which illustrates the famous Black Stairs in the Caithness community’s Pulteneytown area.

There was no grand “look at me” affectation as he eventually packed up his brushes and departed to a nearby hotel.

But if he was a little-known figure at the time – and he regretted that his fame only arrived after his mother’s death in 1939 – there was no denying the power of the picture that Laurence Stephen Lowry produced.

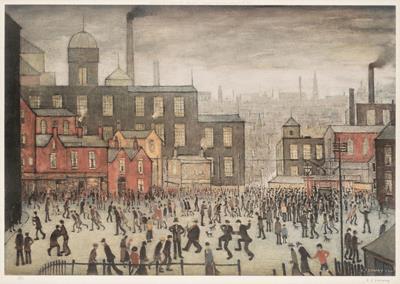

He might be best known these days for his scenes of life in the industrial districts of north-west England – in and around Pendlebury and Salford in Lancashire – and his urban landscapes, filled with human figures, often referred to as “matchstick men”.

But Lowry made regular visits to Scotland, relished painting on the Clyde, holidaying in Berwick-on-Tweed and bringing places in the far north to a wider audience.

And such was the interest in the aforementioned Steps at Wick that it sold for nearly £900,000 when it was put up for auction in 2013.

Lowry, who was a contradictory, reclusive character, always maintained that he had endured an unhappy childhood, growing up in a repressive family atmosphere where his sickly mother, Elizabeth, showed no appreciation of his interest in art.

But it was with his aunt Mary that he first visited Scotland.

As a young boy on holiday, he became fascinated with the industrial landscapes and the allure of the sea: two passions that would remain with him for the rest of his long life.

‘You don’t need brains to be a painter’

Journalist and broadcaster Shelley Rohde was one of the few people who forged a close friendship with him.

Her documentary, L S Lowry: A Private View, was made after she had interviewed the artist personally, which she did on several occasions.

This was in itself no mean achievement – Lowry was known to be difficult to pin down to any interview appointments and was inclined to amuse himself by making up stories.

During one of their meetings, he told Rohde he had given up painting long ago, but she noticed that the paint on a nearby canvas was wet.

And she also chronicled his trips to Scotland, which began as early as the late 1890s.

Rohde wrote: “‘It was not often that Mary was able to persuade Elizabeth to allow Laurie (the family moniker for Lowry) to visit on his own; but in 1898, while her sister was in the throes of an ‘attack’, she took the 10-year-old boy with her own family on holiday to Scotland and they travelled to many different parts of the country.

“They hiked across rough moorland, they visited local tourist spots, and explored the countryside on bicycles which they hired by the day.

“Following this initial introduction to the country, the artist made a number of visits to Scotland throughout his career, holidaying there and travelling as far north as the Highlands where he immersed himself in the remoteness of Caithness.”

Lowry was fascinated by the sea and by ships, and produced several paintings of tramp steamers on the Clyde when he visited the region in 1946 and 1947.

During this period, he also produced a series of paintings of Glasgow docks and was effusive about the attractions of the Scottish coastline.

He said: “It’s the battle of life – the turbulence of the sea. I have been fond of the sea all my life, how wonderful it is, yet how terrible it is.

Art for art’s sake was his maxim

“I often think: what if it suddenly changed its mind and didn’t turn the tide? And came straight on? If it didn’t stay and came on and on and on. That would be the end of it all.”

This might sound profound, but Lowry regularly dismissed the idea he was “any kind of intellectual” and often quietly mocked the art establishment, which continually looked for hidden political or cultural meaning in his work.

As he said: “You don’t need brains to be a painter, just feelings.”

Lowry was not so much secretive on his travels as somebody who refused to court publicity, but he was perfectly civil to those who met him in Caithness.

One local resident described him as being “very quietly-spoken, but pleasant company” and another spoke of how he was very interested in working-class history and heritage.

The various works he created in the Highlands included a striking sketch of the Turnpike, a two-storey building in the Fisherbiggins area of Thurso.

Then, just a few miles along the coast at Wick, he painted the Black Stairs, the flagstone steps which were built in the 1820s and whose style piqued his attention.

Engineer Thomas Telford was in charge of the planning of Pulteneytown for the British Fisheries Society amid a boom in herring fishing off the far north-east coast of Scotland.

And, although it may sound strange at this distance, Wick was Europe’s largest herring port from the 18th until the early 20th Century.

Its rugged nature struck a chord with Lowry, who explained how he had developed his unique matchstick style by addressing subjects nobody else had covered.

Dislike soon turned to infatuation

As he said: “We went to Pendlebury in 1909 from a residential side of Manchester, and we didn’t like it. My father wanted to go to get near a friend for business reasons.

“We lived next door, and for a long time my mother never got to like it, and at first I disliked it, and then after about a year or so I got used to it, and then I got absorbed in it, then I got infatuated with it.

“Then I began to wonder if anyone had ever done it and it seemed to me by that time that it was a very fine industrial subject matter. And I couldn’t see anybody at that time who had done it – and nobody else had done it, so why not me?”

Although Lowry died in 1976, aged 88 – and he turned down five different honours, including a knighthood – his legacy lives on in popular culture.

In 1968 the fledgling rock band Status Quo paid tribute to Lowry in their first hit single, Pictures of Matchstick Men, which led to them appearing on Top of the Pops.

Then, in 1978, Brian and Michael reached number one in the UK singles chart with the tribute single Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs.

Manic about art and music

Oasis released a music video for the song The Masterplan, to promote their 2006 compilation album Stop the Clocks, using animation in the style of his paintings.

And Lowry also features in the chorus of the Manic Street Preachers’ song 30-Year War on their 2013 album Rewind the Film, which includes the words:

“So you hide all Lowry’s paintings

For 30 years or more

‘Cos he turned down a knighthood

And you must now settle the score.”

Most recently, the 2019 film Mrs Lowry & Son, directed by Adrian Noble and starring Vanessa Redgrave and Timothy Spall, depicted the fraught relationship between Lowry and his elderly bed-ridden mother between 1934 and 1939.

Even young people in Wick are familiar with the famous Lowry painting, which sold for £890,500 at an auction in London eight years ago.

A group of primary school pupils staged a re-enactment of the Steps at Wick painting earlier this summer when they took part in a heritage walk around Pulteneytown.

The primary four youngsters from Noss Primary School stopped off at the Black Stairs and arranged themselves in a similar way to figures who were depicted at the steps.

LS Lowry and learning in Caithness

Class teacher Melissa MacGregor said: “This term, P4 have been learning about Wick for their class topic.

“The children are very interested in the history of Wick, especially the harbour, the Black Stairs and the Bank Row bombing.

“For an art lesson, children created their own drawing of the famous Lowry painting.

“The class thoroughly enjoyed the trip and were delighted at recreating it.”

It seems as if Lowry isn’t getting the brush-off any time soon.