In 1944 baby Kathleen Hagler was smuggled out of Munkács ghetto in Hungary. When her rescuer returned a fortnight later for the rest of her family they had all been deported to the Auschwitz death camp.

To commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day, the Inverness octogenarian tells Lindsay Bruce her remarkable story of survival, and pays tribute to her mother, father, sister and brother who all perished at the hands of the Nazis.

Harrowing truth revealed

Kathleen Hagler – better known as Kathy – was eight years old when she found out the woman bringing her up was not her mother.

A teacher at her Budapest school asked each of her pupils what their parents did for a living. When she got to Kathy no answers were to be had.

“She asked me, ‘What does your father do?’ I said, ‘I don’t know’. She said, ‘Well, is he dead?’ I replied again saying ‘I don’t know.’ For me, the idea of having a dad was alien. I lived in a house with my mother and my granny. I didn’t know I was supposed to even have a father.

“That day the school sent a letter home. I think it forced their hands and I was later told that my mother – as I knew her – was actually my aunt, and that my parents had been killed.”

Jewish upbringing

Despite having many more questions Kathy was rarely given any more details. Very occasionally she found out a snippet of information from her granny but no matter what she asked her aunt she was simply told “I can’t remember”.

She did know one thing: she was Jewish.

Clutching her Star of David necklace as we speak she describes how they ate kosher food and that her grandmother – Rebekah (Paula) Stern – kept her hair covered.

Kathy was also taken to synagogue six times a year where she was made to recite Yizkor, a prayer of remembrance.

“But I didn’t know why at that time,” said Kathy, now 81 and a retired journalist. “I was just told it was to remember family.”

Taken never to return

Though raised in Budapest, she came to know that she had been born in Munkács in 1942. An area of modern-day Ukraine now known as Mukachevo, it was then Hungarian, and an area steeped in Jewish culture and community.

Her father, Zsigmond Hagler, came from that Subcarpathian region and met her mother Regina Blank when she became sick and was sent to hospital in the mountains to recover.

The couple married and started a family. They had a son Lajos, then baby Judit who died in infancy. Next came Kathy, Katalin on the Hungarian birth certificate which was completed in Russian.

When Kathy was just a baby her father was “taken”.

“My granny once told me that he was, like all the Jewish men at the time, taken to fight in the Hungarian army for the Germans. At that time Hungary and Germany were on the same side.

“He left before knowing my mother was pregnant again with Eva. And he never came back.”

Smuggled from the ghetto

In 1944 things changed politically and from a safe haven for many Jews who had experienced pogroms in Russia and surrounding areas, suddenly the Jews of Munkács were rounded up and forced to live in a former brick factory.

The ghettoisation of the town and rumours of what was to follow led Kathy’s family in Budapest to take action. They paid a man known to the family who regularly rode the train from Munkács to the capital, to smuggle out nine-year-old Lajos.

“But when he came for my brother they found out he had something like German measles. He took me instead.

“When he came back about two weeks later to get my brother the entire ghetto was empty.”

‘It should have been me…’

From May 15 to July 9 1944, under the guidance of German SS officials, around 440,000 Jews from Hungary were deported, most to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon arrival, the majority were killed in gas chambers.

Thousands were also sent to the border with Austria to be deployed to dig fortification trenches. By the end of July 1944, the only Jewish community left in Hungary was that of Budapest.

“Do you know about survivor’s guilt?” she asks me. “I didn’t have the words for it back then but when I did my research and learnt what I had been saved from I found it hard to come to terms with. It should have been me who died and my brother who lived,” said Kathy.

Post-war poverty

Though times were hard and many of their Jewish community in Budapest were also killed, Kathy, her granny and aunt, Rozsi Blank, survived.

Experiencing poverty, their potato-based diet was poor and Kathy developed rickets. The lasting effects still impact her health today.

“I was 12 before I ever tasted butter and when I did I thought it was heaven. I sneaked back up in the middle of the night and ate it all like a bar of chocolate. It was not good for me when they found out,” she giggles.

Answers sought

Desperate for answers as to what happened to her parents Kathy secretly learnt German to listen to what her aunt and granny spoke about.

“I feel like I was stupid and clever in equal measure,” she said. “On the one hand, I loved school and my education. It was perhaps the most important thing in my life. I loved science and maths and always wanted to know more and ask more.

“But on the other, I came from a family where you did not question anything. If I was told ‘I don’t know,’ that was it.

“I didn’t know what I should ask, or who to ask. I still don’t!”

More heartache for Kathy

By the age of 14 Kathy had been plucked to safety from deportation trains, she had survived the clearing of Jews from Budapest and then was about to live through the Hungarian Uprising of 1956.

“I remember that vividly,” she says. “I think I’m perhaps good at handling war. And I am confident in calling myself a survivor!”

Then age 16, Kathy and her family sought refuge in Israel. Overwhelmed by the heat and upset that her education had been disrupted, she then lost her grandmother.

“To illustrate just how little I was told. I came home from being away at school and asked where my granny was, only to be told she had died. They hadn’t even told me that!”

Israel to Inverness

Working in a cosmetics factory before living in a kibbutz, Kathy would once again experience life living through conflict.

The Six Day War, the War of Attrition and Yom Kippur War all took place during her time in the Israel.

By the mid 1970s she felt unsettled as the “political sand began to shift” and following a holiday to Scotland she decided to move to Inverness permanently.

“I felt an affinity with the Scots. They also know what it’s like to be oppressed. And I preferred the weather!”

‘We must never forget’

Starting her new life working in a metal detector factory she’d later have a career as a journalist with the Inverness Courier. Despite reporting the news, opening up about her own historical story wasn’t so easy.

“There’s just always something at the back of my mind that said ‘if they know you’re a Jew they will kill you. That’s how I felt. That’s how I can still feel.

“I never ever lied about being a Jew but I was never very open either.

“It was only as I got older and thought well Kathy, you’ve lived now, it won’t matter if they come for you. It was then I decided it was time to use my voice and my story to make sure a new generation don’t forget the Holocaust.”

The ‘six million’

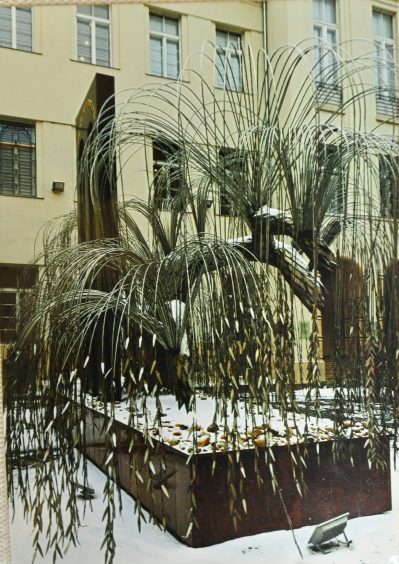

Armed with years of research, and even a copy of her parents’ names recorded in the “book of death” at Auschwitz, Kathy began speaking to schoolchildren about the Holocaust.

“I always start by asking if they know how many people are in Scotland. Then I get them to imagine what they would think if someone wanted to kill every single Scot, here and around the world, just for being Scottish.

“That would be about the same number – six million – as how many Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.”

‘I wish I could do more’

To mark Holocaust Memorial Day, marked this year on January 27, Kathy will be attending an event where six candles will be lit.

“One for every million Jews killed,” she says. “I just wish I could do more to refute these so-called (Holocaust) deniers.”

It’s the first time I’ve seen her hand shake – her self-confessed “tell” that she’s upset.

“I feel that there’s no answer for them. I doubt if there had not been a Holocaust the German government would be paying pensions or sending me money as compensation for the murder of my parents! It’s stupid. And there is very little you can do, except tell your own story, in the face of such stupidity.”

What could have been

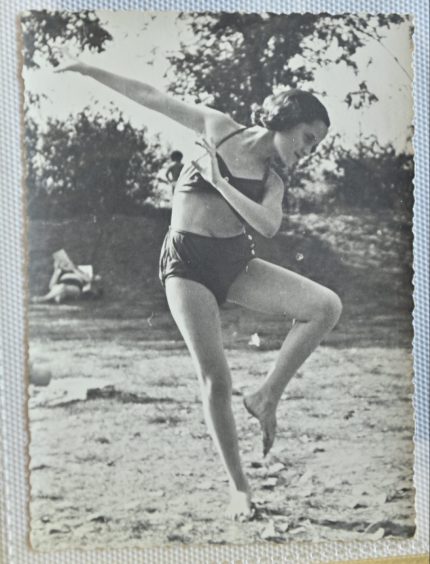

As the interview draws to an end, flicking through photos and smiling, she looks up. Her distinctive twinkly blue eyes – evident in all the pictures her grandmother preserved, are more alive than I’ve seen them.

“You know,” she muses, “I was thinking. If my brother had lived I would probably have married one of his friends.”

As it stands Lajos did not survive, and Kathy never married.