A short film has shown what life on the island of St Kilda was like in 1908.

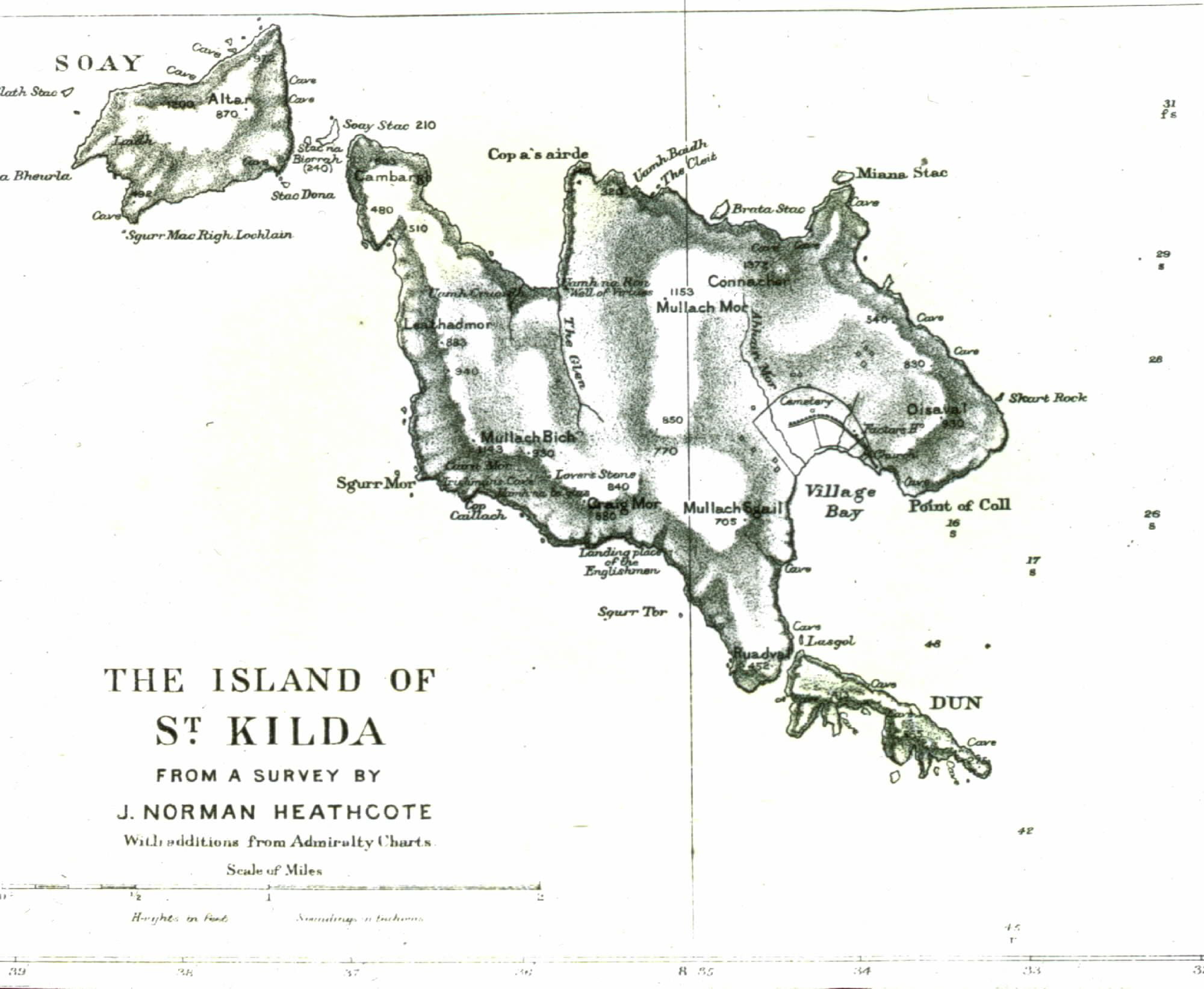

The clip, shared on the St Kilda Rangers Twitter page, gives a glimpse into life on the remote island which sits out in the Atlantic 41 miles west of Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides.

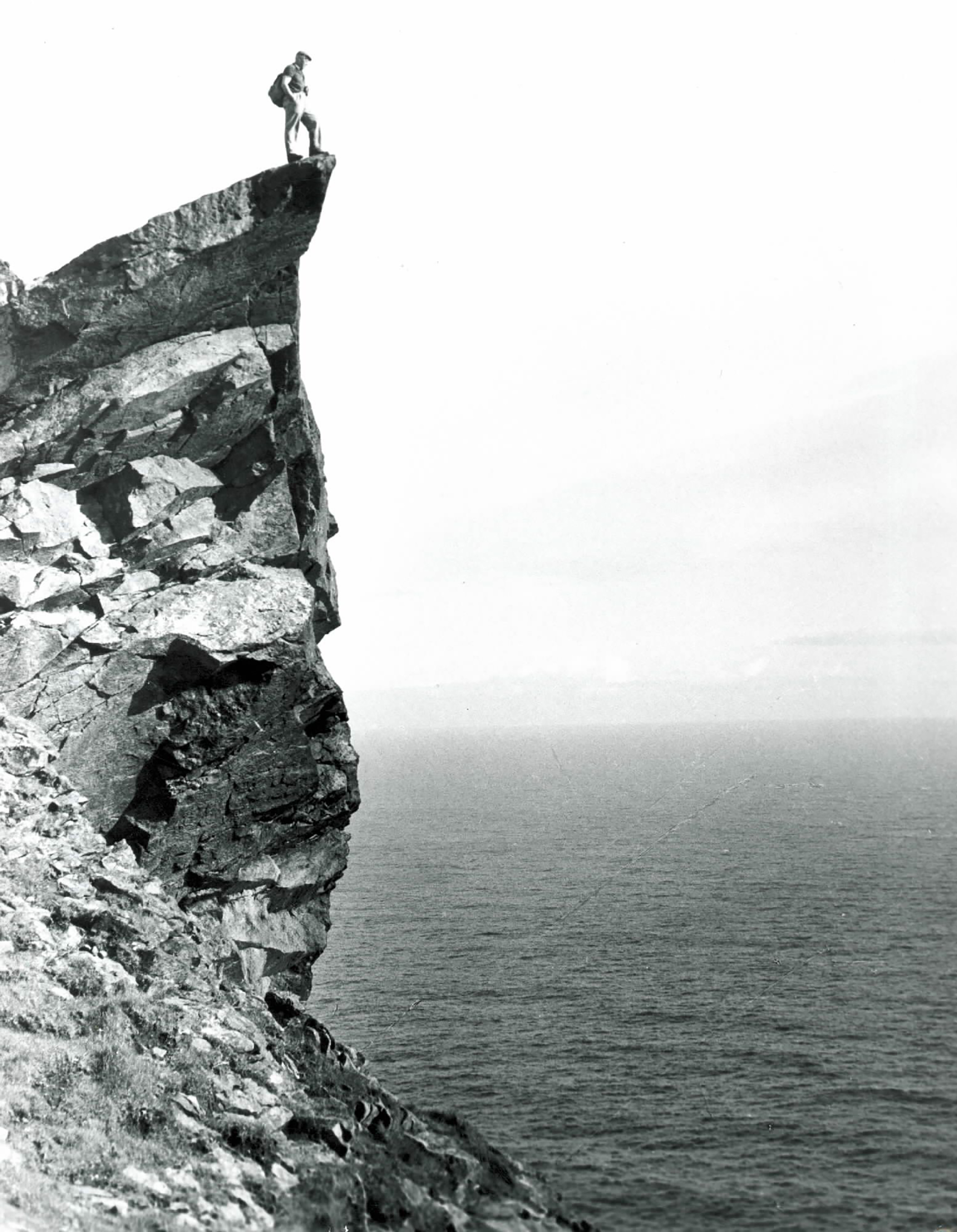

St Kilda is the UK’s only dual UNESCO World Heritage Site with a rich and complex ecological system.

It is also home to the UK’s largest colony of Atlantic puffins and the largest seabird colony in the north-east Atlantic.

The archipelago has been considered a source of fascination over the years, largely due to its isolated location and lack of inhabitants.

Now maintained as a heritage site by the National Trust for Scotland (NTS), the last of its residents abandoned it in 1930.

In the years prior to this it had seen a sharp population decline; at its peak the island was home to around 200 residents.

But after the First World War many of the young men left, leaving less than 50 inhabitants in 1928.

Following a bout of influenza in 1926, which claimed the lives of four men, islander Mary Gillies died.

Her death was the final straw for many; the catalyst for the evacuation. Mary was pregnant and suffering from appendicitis, so residents signalled for a passing ship to take her to hospital.

The sea was rough and the weather stormy so the ship left without her.

Days later they flagged down a second ship and this time she was taken off the island – to Glasgow’s Stobhill hospital.

Mary died on May 26 1930. Her 13-day-old daughter died that same day.

In the August of that year the remaining 36 residents – 13 men, 10 women and 13 children – were collected from Hirta, the largest island in the St Kilda archipelago, by HMS Harebell.

Islanders had petitioned the government for resettlement on the mainland, desperate for the opportunity of a life elsewhere.

The last remaining St Kildan, Rachel Johnson, died aged 93 in April 2016.

Craig Stanford, a St Kilda archaeologist, and Ciaran Hatsell, the St Kilda marine and seabird ranger, are two of the three NTS staff who live on the island for nearly six months of the year.

Alongside the St Kilda ranger, the trio look after the islands and its visitors, protecting and conserving its natural and cultural heritage.

For them the silent film, produced by British Pathé, offers a fascinating insight into how the islanders lived in the early 20th Century.

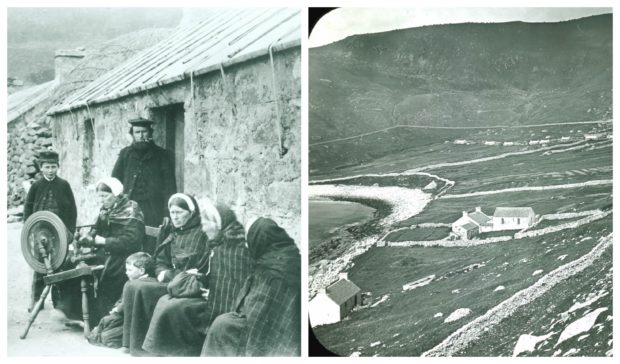

Mr Stanford said: “Most of the faces in the film are quite familiar to me, having stared back at me from books, the displays in the museum and schoolroom on St Kilda, or from the extensive photographic archive we maintain.

“The St Kildans in the video have the look of people used to tourists; after all St Kilda has been a tourist destination since 1697, when the Gaelic speaking writer Martin Martin visited and later published a widely read account of his time there.”

He went on to note that there were a number of aristocratic visitors in the 18th Century, and from the 1830s chartered steamships started to call in regularly.

They would announce their early morning arrival with cannon fire and brass bands playing.

From the 1870s there were regular steamer services from Glasgow in the summer months, bringing visitors who made the journey to experience ‘Scotland’s last and outmost isle.'”

“When this film was shot, the St Kildans would have been used to cameras and photographers; the earliest known photographs of St Kilda date to the 1860s.

“This deep fascination and interest in St Kilda was often due to a desire to experience a ‘primitive’ way of life.

“The British Pathé film belongs very much to its era in that way, with words such as ‘primitive’ used to describe their fowling techniques,” said Mr Stanford.

He is keen to point out that the people in this video are dressed “much the same” as their neighbours in other Hebridean islands. They spoke the same language, belonged to the Free Church of Scotland with a resident minister, had a school and resident teacher, and had their own dedicated resident nurse.

Houses were relatively modern with glass windows and the furniture was bought in the markets of Glasgow by their minister using rural improvement funds.

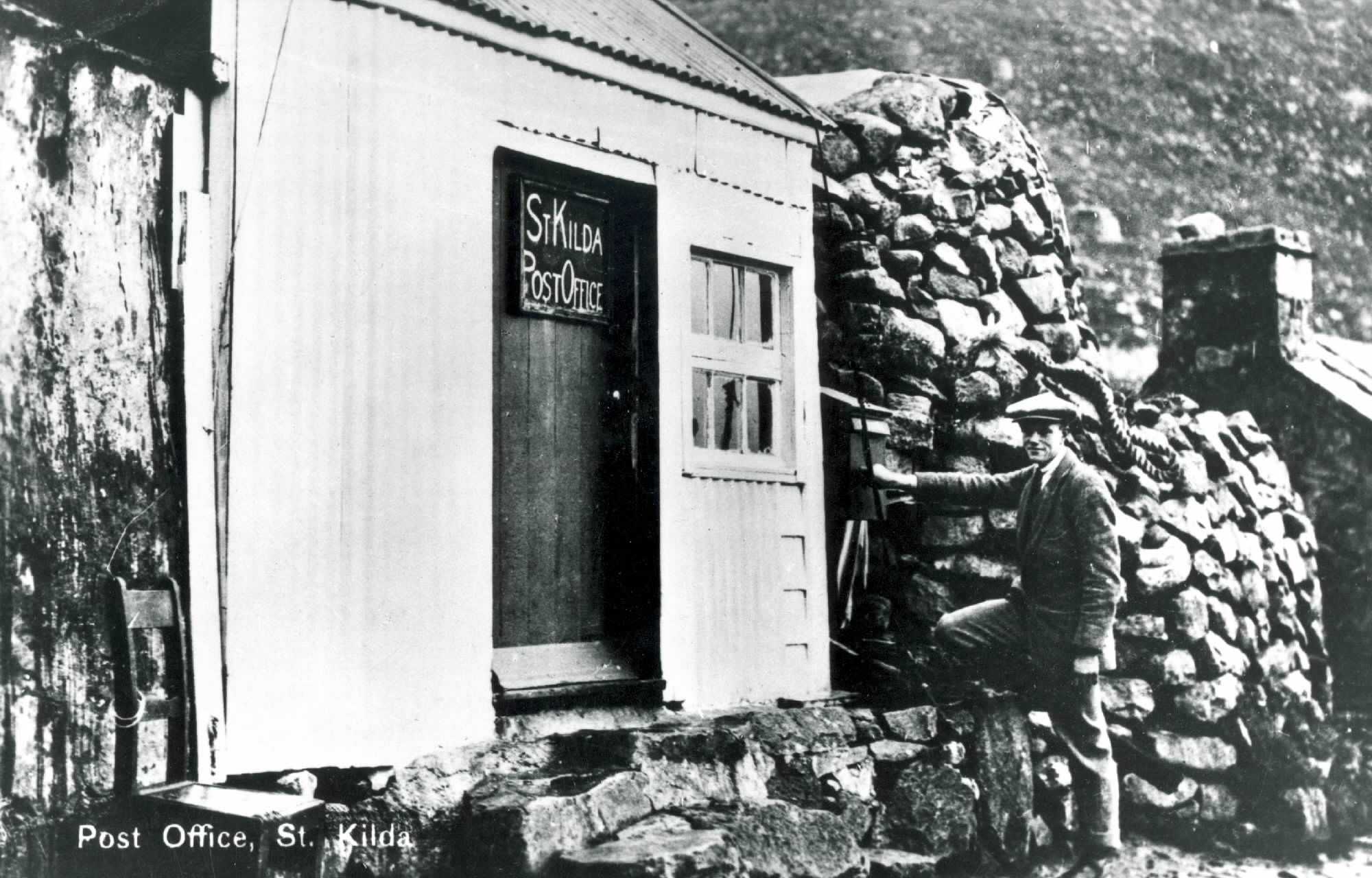

Mr Stanford says that the video opens with the “classic misunderstanding” that St Kilda was totally cut off from the rest of the world.

Though the sea undeniably acted as a barrier during the winter months, in the summertime the island was well-connected to the rest of the McLeod estate, as well as to the networks of fishermen, whalers and tourists.

One St Kildan, Alexander Ferguson, moved to Glasgow in the 1890s when he was 20 years old.

He was vital in ensuring links between the island and the rest of the world remained; he set up a tweed shop and enjoyed a relatively significant amount of success. He would visit his former home until the evacuation, buying and selling fuel, food and supplies.

“The film is fascinating, to see that the landscape, the houses, walls and cleits have all changed very little.

“The stones that the St Kildans laid are mostly still there with very little change – it is an incredible feeling of connection.

“The incredible preservation of the St Kildan landscape is largely due to the hard work that the National Trust for Scotland has put into conserving the place, work which is only made possible through our membership and kind donations,” said Mr Stanford.

The only way to reach St Kilda is by boat, a journey which takes approximately 2.5 hours. A number of companies offer trips there including: