To watch Iain Craigie tend his vegetable patch is to see a perfectly ordinary grandfather at home in rural Aberdeenshire.

You would perhaps say a quick hello were you to spot the 81-year-old, as he enjoyed a fly cup before returning to digging.

It’s an unassuming sort of life, a retirement well deserved after decades of adventure.

But despite the passing years, Iain rarely discusses his extraordinary journey – perhaps because secrecy is ingrained.

He jokes about going to prison, were he to reveal the past.

Serious consequences would have once been a very real possibility, and even loved ones were kept completely in the dark as to the nature of Iain’s work.

It is only now, and in part thanks to Iain’s daughter, Jane, that he can talk openly about a career spanning almost 30 years.

The pair have created a podcast, which is already reaching people around the world.

We caught up with Iain to ask how a former tax office worker rose to be a senior figure in intelligence at Bletchley Park, once the top-secret home to codebreakers.

The grandfather of 11 has lived all over the world, and was sent on countless missions to gather information during The Cold War.

From listening in on Russian training exercises, to witnessing first-hand the tensions leading up to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, what was life really like as a spy?

I never set out to work in intelligence but I did have a strong desire to see the world.

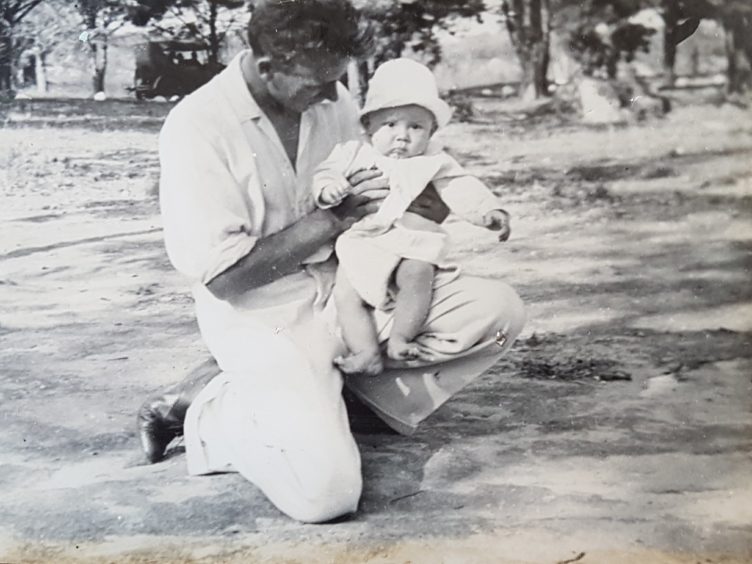

I was born in southern Rhodesia in 1938, my father worked there as an engineer. It was quite a normal thing for people from the north of Scotland, especially in rural areas, to go to Rhodesia.

There was a lot happening in Africa at that time, the setting up of farms and so on.

Prior to the war in 1939, my father decided we would come back to the UK. It would have been quite the journey, which included catching the train across the Kalahari Desert.

We arrived home to a country driven by the start of war. We rented a one-bedroom cottage in Urquhart, near Elgin. There were five of us sharing that space.

The cottage was on the flight path of German bombers flying back to base. You’d hear muffled bangs in the night.

So I was evacuated with my brother, Grant, and sister, Jean. We were sent two miles down the road to live with Miss Jackson. She used to dig up tatties from the farmer’s fields and shoot deer to feed us.

These were fairly desperate times, you lived hand to mouth.

My father had been posted to Palestine, and when he returned, we got a house in Kingston on Spey.

My early memories are of going up the garden to dig a hole, so you could go to the toilet.

Of course, you had to remember where you had last dug. We had a neighbour called Mrs Middleton; she’d look over the fence and say “you cant put it there, you did it there last week”. So we’d have a conference, who dug the last hole and where it was. That was good fun, it was a completely different era.

There was a small school in the village with 30 children, perhaps. There was no paper or pencils, because there were barely any supplies after the war. We used slates for writing on, and hard sharply pointed slate pencils.

The thing I remember the most is that we had the freedom to explore.

Eventually there was one bus a week in and out the village, but you had to amuse yourself.

We were all fishers, salmon poachers. We were an unruly bunch really.

I volunteered for a three-year spell in the RAF, and that’s where I got my background in intelligence gathering.

My first posting was to Hong Kong where I spent a year, followed by a small island off the coast of Borneo called Labuan, doing surveillance work.

The interest was China of course, we had to keep a very close eye on what the Chinese were doing. Upon my return, I joined the tax office in Buckie.

Then I saw that the war office was asking people to join their intelligence-gathering network. My background with the RAF helped and off I went to Bletchley Park.

It was 1964; I was based there for nine months. It was a basic introduction, learning different techniques in surveillance, direction finding, radio and codes. It was all very odd because in that era, there was a need for secrecy.

It was impressed upon us when we got there, if you had a wife, and your wife moved to that area, she had to be outside a radius of 30 miles.

You couldn’t look for accommodation in Bletchley together.

The sensitivity of the work you were doing, the line of thought meant you might be tempted to chat with your wife about it. Our loved ones didn’t have a clue what we were doing most of the time, you never talked about it.

Then we moved to near Loughborough; there was an Army camp used for the intelligence effort. By that time, Russia was a serious threat to the UK.

We worked closely with Americans, New Zealand and Australia

Russia was always looking for opportunities to spy on us. In return, we needed to know what the submarines were doing, what the battleships were doing and where they were going.

We were keeping a tab on their ambitions, we deciphered the information and it was passed on to various government departments.

The Russians were not that well trained when they started foraging about in Europe. They’d do exercises in certain areas, they used to get lost. We were trying to find out where they were conducting these exercises. You’d hear a voice somewhere, “we do not know where we are”. Then they’d find a signpost and read out the location.

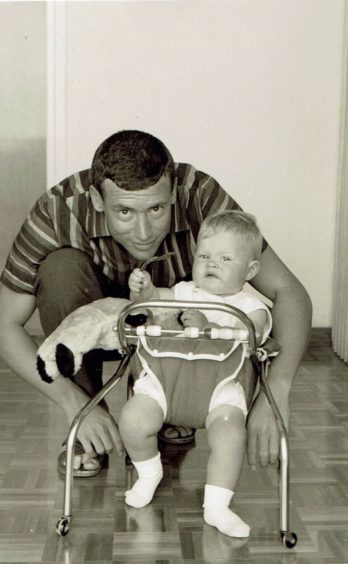

I was sent to Cyprus in 1965, it was a three-year posting. It was a totally different experience to what I’d had in the UK.

Oil was becoming very important to Europe and to America. Cyprus was very convenient geographically, but the island was in conflict. There had always been a lot of strife between the Turkish and Cypriot community.

We decided to drive to Cyprus, it was a bit of a journey. We set off in February, to drive across into Italy to pick up a ferry.

There was heavy snow most of the way, and I had an Austin Healey with a soft top. One of the mountain passes was horrendous. If you met another car, you could either reverse or nudge into some of the little caves that other vehicles had left on the side.

We arrived in Cyprus at last, it was incredible. The freedom, there was virtually no people then, no hotels.

In Ayia Napa, there was nothing except for one old fisherman. He would catch some fish and barbecue it for you.

The locals would use dynamite to fish, so there was a lot of people with missing fingers.

Oil was of great importance – if you had a supply you could do wonderful things

It was all about the control of which countries had oil, and how they negotiated deals.

We had targets in Iraq and Iran, we were listening in to transmissions to see if we could deduce what deals they were doing, find out how they were transporting it.

It was about keeping a finger on the pulse, and we had to learn the adaption of Morse code in Arab nations.

Then we went to Istanbul for two years, New Delhi for another two years.

I was posted to Saudi Arabia by myself for one year – that wasn’t a family trip.

Then on to Hong Kong, followed by a stint at the embassy in Turkey. That was the last of proper overseas postings.

There was huge advancement and communications had improved, a lot of it was by satellite.

I took early retirement in 1992 when I was 58, and we finally returned to the north-east – to run an equestrian business near Turriff.

When I look back, life was so full of things to do.

You never get the opportunity, the time and space to think about it. It’s only when I look at pictures that I think, my God, I had forgotten that.

I don’t tell many people about my career in intelligence, it’s not the sort of thing you discuss.

Once you’re removed from the intelligence field for 30 years, people are not too bothered if you divulge things anymore.

I do miss it, I get restless every three years and want to move again.

I think one of the most important things was the interaction with people. It gives you insight into different countries, not just on a superficial level.

You got a deep connection with the country, partly because you knew all sorts of things that were going on.

I think I’ll always have a lifetime interest, it becomes part of who you are when you’ve worked in intelligence.

I always had a hankering to go and do something, I just didn’t know what. That hankering was certainly fulfilled. Now I have to try and find other ways to explore, by getting abroad when I can.

Canoeing down the Zambezi River for example, that has made a very good substitute.