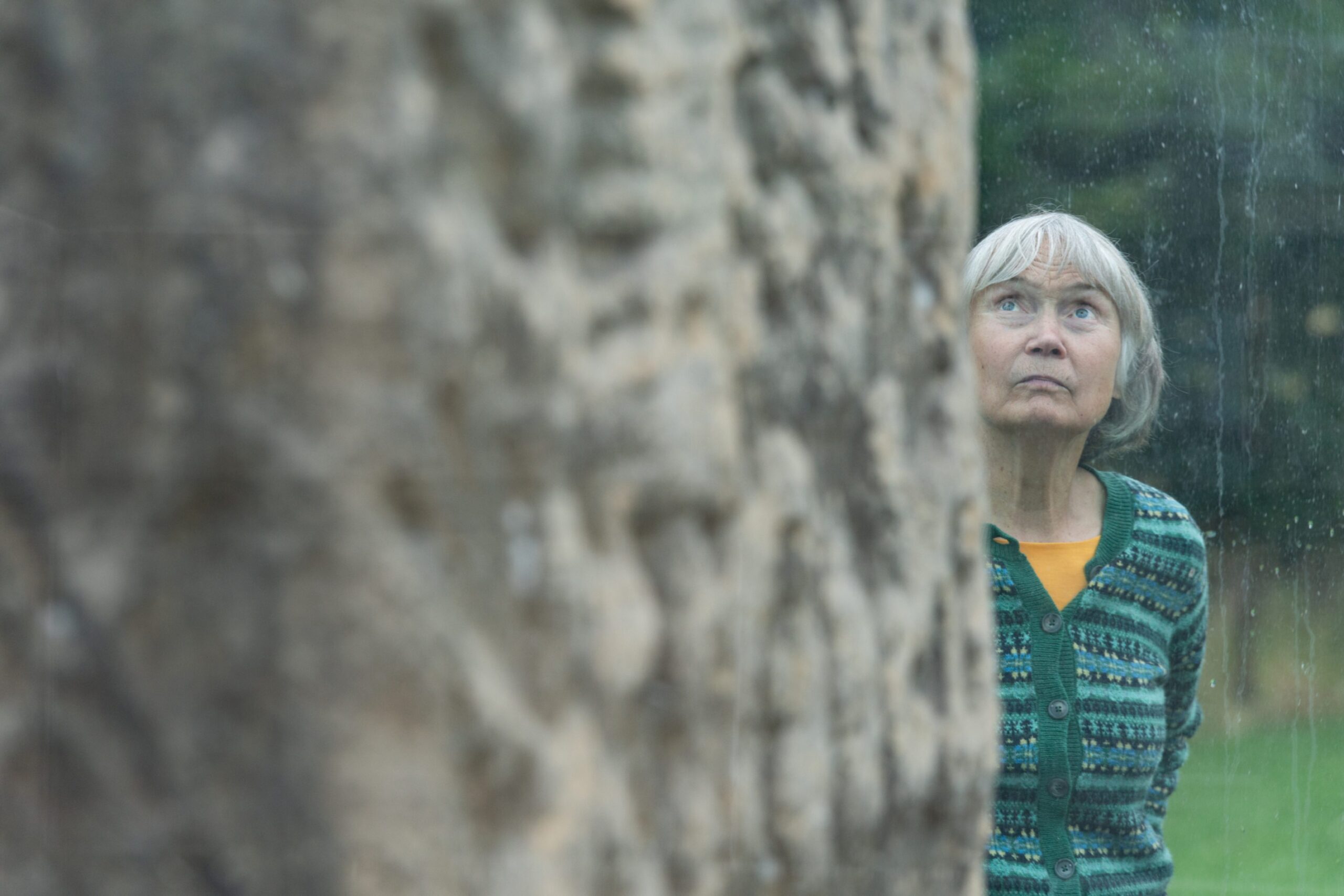

In Forres, just off the A96, there is a 21ft-tall stone which has been surrounded by mystery, legend and glass.

Named after a Viking king who never visited Moray, Sueno’s Stone has attracted a whole host of theories.

It has even been said Sueno’s Stone is where Shakespeare’s Macbeth met his three witches at a crossroads and that their souls are trapped within it.

The meaning of the giant monument and the etchings of a cross and a battle on its surface has left some puzzled.

Especially as some wear and tear and the sunlight glinting off the glass surrounding the stone makes it harder to see anything.

However, thanks to an old cast, fancy technology and new drawings, Professor Jane Geddes said the Pictish stone can now be read properly for the first time in hundreds of years.

And the results are chilling.

‘We’re seeing something that was not possible before’

The new drawings were carried out by John Borland, the draftsman for Historic Environment Scotland.

By visiting the stone inside the glass box, using old photographs, studying an old plaster cast taken of the stone and then taking a full digital scan of the cast and rolling light sources over the scan, John has been able to see more than anybody has ever done before.

Jane said: “These drawings are a miracle because they allow us to see what you absolutely cannot work out with the naked eye.

“No previous artist has looked at it in detail because it’s just too big to take in.”

Why is it called Sueno’s Stone?

In the 17th Century, a violent battle depicted on the stone was thought to be a Viking story relating to King Sweyn Forkbeard (or Sueno) of Denmark who died in 1014, apparently fighting the Scots.

“Because of that it’s always been called Sueno’s Stone, although actually it’s got nothing to do with Sueno,” said the former professor of History of Art at Aberdeen University.

“It was very difficult to shift that name from it.”

Over the years, other opinions suggested it could be showing a battle between the Picts and the Scots.

“But now with drawings, we can see what it really is,” said Jane, 74.

“I think it’s incredibly important because it’s a very vivid, contemporary event that happened a long time ago with no supporting documentary information.”

With some carbon dating done by professor Gordon Noble at Aberdeen University in the postholes around the site, the research confirmed the stone was erected in the late 800s.

Jane added: “And that is slap bang in the middle of the terrible time when the Vikings started to invade.”

A few Bible stories might hold the key to a ‘mysterious’ scene

The Pictish stone is made up of two faces.

On the east side, there are scenes of violent fighting.

On the other, there is an “enormously” tall cross with a “mysterious scene” underneath picturing five people.

The scene pictures a small person in a tunic with two bigger people leaning over him holding his arms up, and behind that are two other people bearing armour.

It’s an image that has been compared to the inauguration of a Scottish king like the one in the Seal of Scone Abbey from the 14th Century.

However, unlike the Scone Abbey picture where the king is enormous, the person depicted is a child.

After studying some Byzantine illustrations of young King David offering to kill Goliath for King Saul, Jane said: “It’s clearly a Bible story they’re telling us. Saul presents David with his royal armour and David throws it off.

“David says, ‘I don’t need your armour. God is on my side.’

“So the first message of this great cross face is that the ruler, the leader, has got God on his side, and he can fight the battle and win it because God is with him.”

Sueno’s Stone is signed by warriors

But it doesn’t stop there. Jane believes there are two other meanings and Bible stories wrapped up in the image due to the positioning of the boy’s arms which are being held up.

“This simple little image has at least three layers of meaning.

“It’s Christ who wins over death, his arms up like the crucifixion, and it’s Moses who triumphs over the Amalekites when his helpers hold his arms up in prayer, and it’s David who wins over Goliath.”

Then at the bottom where there would usually be an inscription, there are gouges thought to be made from warriors grinding their swords across the stone pledging an oath to their king.

‘A poem turned to stone’

“You’ve got two men in the middle fighting, and one is cutting the other chap’s head off.”

We are onto the violent side of the stone. And there is a lot to unpack.

Carved into the monument are 80 people fighting and dying all over it including some horses and dogs in what looks like a “terrible slaughter”.

With rows and rows of single combat, it seems the same scene is repeated over and over again.

But it reminded Jane of a very early old heroic Welsh poem, the closest we have left to Pictish, a language and group of people lost in time, called the Y Gododdin.

Described as an “incredibly poignant poem”, it talks about all these heroes who go off fighting and are killed.

Looking at the stone, the former Coull resident added: “It’s almost word for word like this heroic poetry.

“It would have been recited by the Bard, and the reason the poem survives is that people wanted to hear the story about their named hero over and over again.

“I think that’s what these repeated lines are doing in stone. It’s like a poem turned to stone.

“It would be a living memorial. Carvers would not provide so much detail unless it meant something passionate to them.

“But then we come to the very difficult bits where the Vikings come in.”

How bad were the Vikings at the time?

There are a few gory details on Sueno’s Stone which point to the fact that the Vikings were seen with horror by the Picts.

One is the canopy of the dead with their bodies separated from their heads.

While decapitation was a popular method in battle for both Scots and Picts, there is an excavation site at Ridgeway Hill in Weymouth with a mass Viking grave, their heads in a pile on one side.

Another is the two poor horses that most people thought were killed in battle.

“But they’re not,” Jane explained. “It’s much, much worse than that.

“If you’re doing a sacrifice, you want to have a whole creature. The way you kill them without damaging their skeleton is by shafting a sword through the skull straight into the brain and they’re doing that there. That’s what Vikings did.”

The animals would be cremated or buried with the warriors.

Then in the middle, there is a conical structure. Some people have suggested this is a bell or Broch tower but again Jane suggests the image is much more Biblical.

“The next idea is that it could be a furnace,” she said. “That’s very interesting, because if you start to look in manuscripts of the Psalms…they write that the pagans go to hell and they’re burnt to pieces.

“So this is saying Vikings are going to go to hell no matter what.

“[All these things] would be completely repellent to Christians so why put this on a holy cross? It is a way to show how horrible and beastly these Vikings actually were.”

Sueno’s Stone in Forres: A memorial to an awful battle against a ‘barbaric’ foe

So what is Sueno’s Stone?

Due to the cross side of the stone, Prof Geddes said it seems like a victory through God over the heathens.

“It’s a memorial to the worst battle anyone had ever experienced against a foe that was so barbaric they could hardly believe anything could be so terrible,” she said.

“It was a cultural shock which required a memory that nobody is going to forget.”

The question remains of who was fighting the battle and when it happened.

While there was an awful battle in AD 839 when the Pictish and Scot rulers were wiped out, Viking incursions continued in this area for decades.

The battle might simply be unrecorded.

But there was a notable victory in 904 when the Viking leader Imar was slain and King Constantin son of Aed went on to rule for forty years.

Jane added: “I think personally after the battle you need to have a lot of money, time and investment to make this and a lot of conviction that you’re going to be around.

“He might have had enough peace to actually put it up.”

However, she does not think this is the end of the story the stone has to tell.

“I don’t think it’s a final answer, but I’ve given an explanation with evidence and a narrative frame that actually would work.

“We’ve just got a much closer picture of the horror that was going on at the time.”

A Scottish Bayeux Tapestry – the stone that’s finally giving the Picts a voice

The large monument is the only one of its kind and yet remains relatively unknown.

Between the time of the Romans and the time of the Picts, Jane said no other culture had tried to create such a massive sculpture.

It’s the Scottish equivalent of the Bayeux Tapestry – which tells the story of the Normans and Anglo Saxons – but 200 years earlier.

“And few people have heard of Sueno’s Stone,” said Jane, who is planning on taking the research to London and abroad to raise awareness about the Forres monument.

“It’s very rare in the early Middle Ages for art to show real events. And here you get the feeling that even though battle scenes are choreographed, this is what happened.

“It’s got a vividness about it and hideous detail that is incredibly true.

“The other thing which I found very moving when I was doing the research, the Picts are silent.

“They have no documents, no story of their own to tell.

“When I started reading these poems like Y Gododdin, which are written in different languages but are from the same era, I suddenly could almost hear the Picts and Scots telling this story, standing beside the stone and reciting how they admired their heroes, how they praised their king and the courage of their people.

“Suddenly it is like a frozen or a petrified poem.”

The full report will be published in the autumn: ‘Reconsidering the Forres cross-slab (Sueno’s Stone), part 2: iconography’ by Jane Geddes, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 153 (2024), 245-69)

Conversation