It was the autumn of 1951, the tattie holidays had been and gone, and all over the north and north-east youngsters were getting ready for the annual celebration of all things supernatural.

But for one wee boy, Halloween that year represented something far darker in his life than the ghosts and goblins of fables and myths and the evil grins on the carved neep lanterns carried door-to-door by guisers.

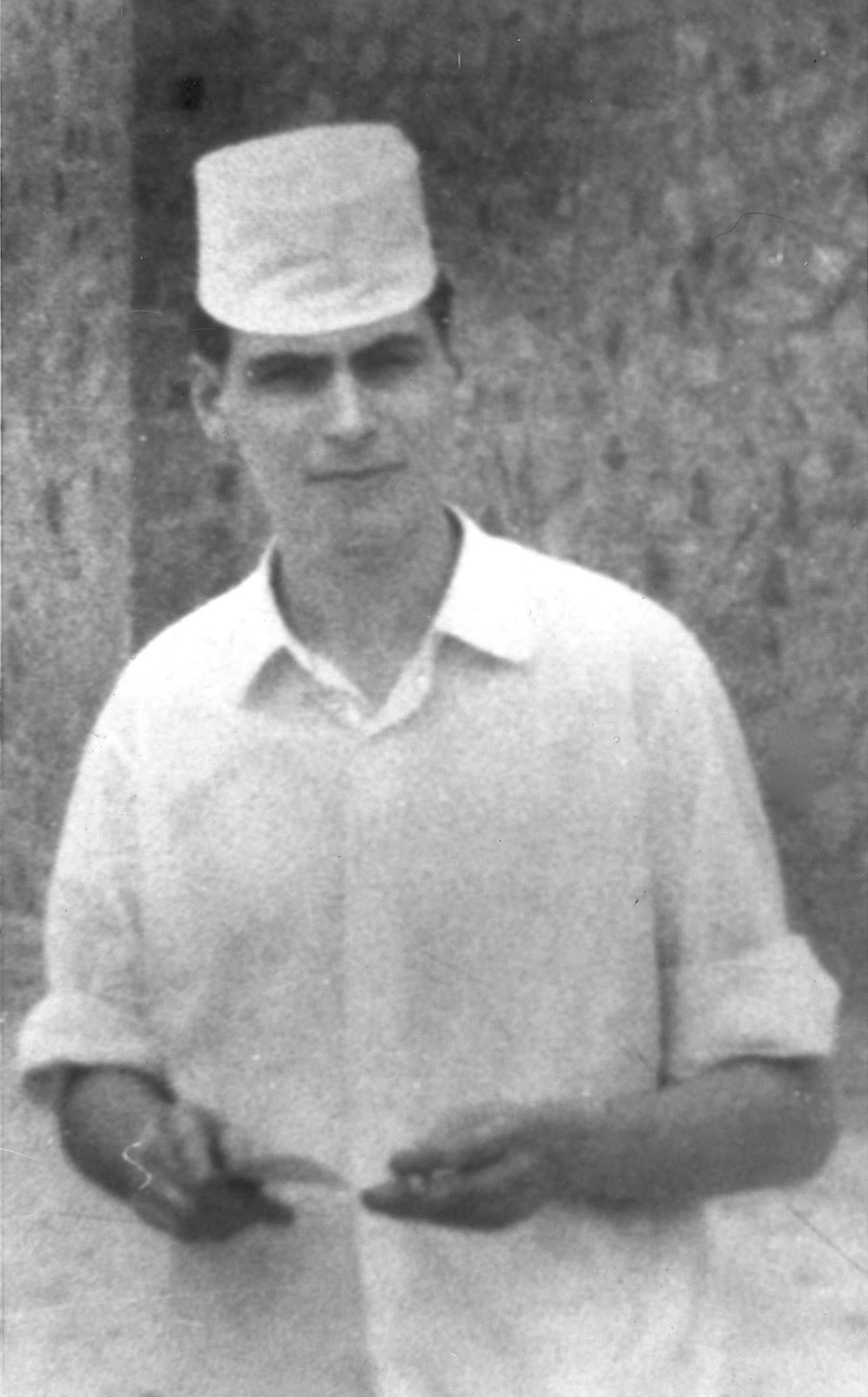

Dennis Nilsen’s dad Olav, who was a Norwegian soldier, spent little time at home, and eventually one day upped and left his wife and children for good.

That meant the young Nilsen, along with his mother Betty Whyte and his two siblings, going to live with his grandparents.

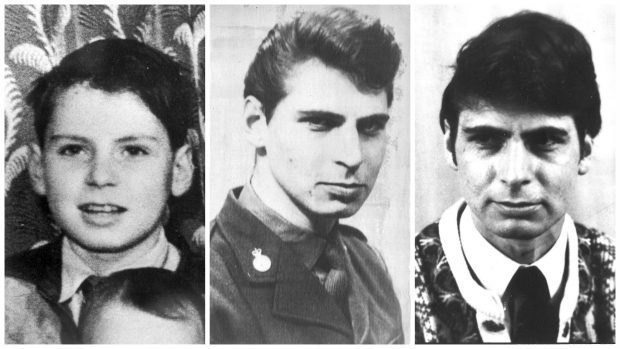

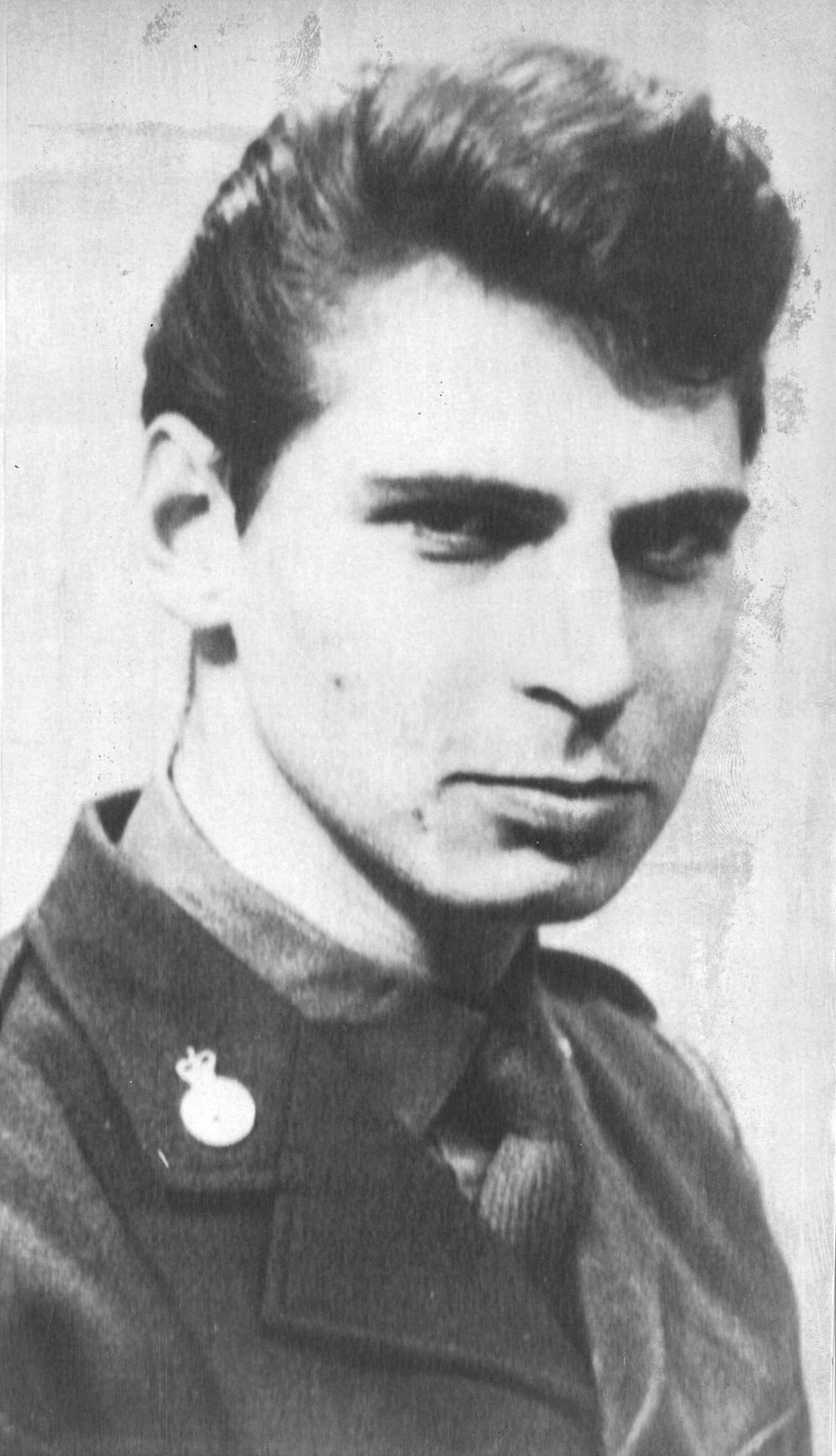

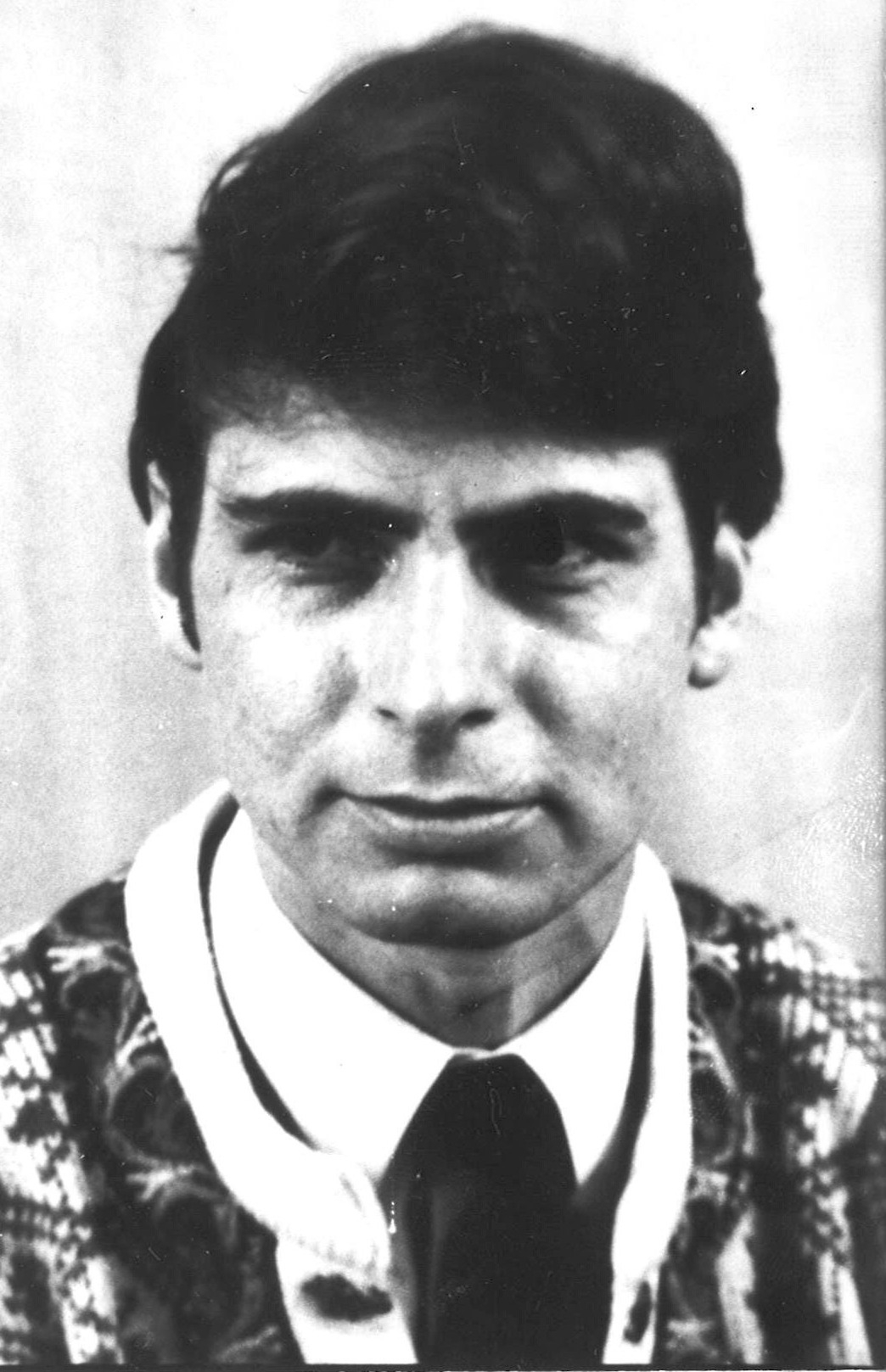

Dennis Nilsen is convinced childhood trauma led to murders

His grandad Andrew Whyte became the father figure in his life, and the pair became particularly close.

When he died, Nilsen was aged just five, still a few weeks short of his sixth birthday.

Effectively, it was the second time a “father” had left him, and he is convinced the trauma of his loss had a lasting impact of him and indeed put him on the path to murder.

After his death on October 31, 1951, Mr Whyte’s body was returned to the family home.

Nilsen’s mother took him to see his grandfather’s body – although she told him he was sleeping.

Nilsen believes it was this failure to explain death to him which provided the catalyst for his shocking crimes in later life

“My troubles started there,” he is quoted as writing in Brian Masters’s book, Killing for Company.

“It blighted my personality permanently.”

In the years after his grandfather’s death, Fraserburgh-born Nilsen spent some time in the nearby village of Strichen before joining the Army Catering Corps and serving across the world, as well as closer to home at Fort George near Inverness and Ballater.

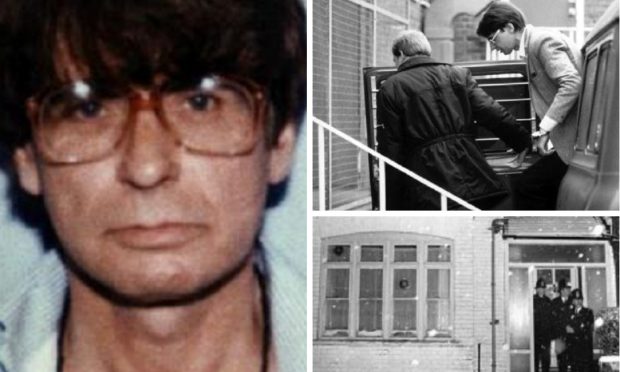

String of gruesome murders

He later moved to London and joined the Metropolitan Police as a cadet, before leaving and embarking on a career at the Job Centre where he was working when his string of gruesome murders was uncovered.

So what was it, more than 20 years after the death of his grandfather, that drove Nilsen to kill for the first time?

Does he still view that childhood bereavement as the genesis of a series of killings which to this day make him one of the most notorious figures in British criminal history?

And does he now – many years after her death – understand his mother’s reluctance to explain the death to a five-year-old?

I never got an answer to those questions, but in his letters to me Nilsen did speak about his childhood in more general terms, despite telling me that asking about memories from his childhood was a “dangerous invitation”.

He said: “I don’t think your readers are interested in anything abrasive to disturb their peace at the breakfast table of their comforts.

“So I will keep my reporting moderate and omit the personal and emotional traumas of social and family interactions.”

He told me there was an instance recently when memories of his childhood came flooding back as he watched TV.

“Alex Salmond was being interviewed live and he was standing on the grassy back of the River Ugie in front of one of the two ‘Ald road Brigs’ which were so familiar to me in Strichen in the childhood years I spent there prior to me joining the British Army.”

He then pointed out that he joined the “British Army“, not an independent Scottish Army, as although “born a Scot”, he remains welded to his Britishness.

Dennis Nilsen has never been ashamed of his origins

He also said he has “never been ashamed of my (then) Buchan Doric speech” or his working class origins.

He added: “Or the Protestant work ethic which was most naturally drummed into me from the first.”

When asked about specific places where he spent his youth he said: “Fraserburgh harbour, Kinnaird Head and Waughton Hill.

“Well, in my formative years, they stood as physical and psychological ‘permanences of uncritical stability in my early boyhood.

“They stood as strong facts that would outlive and outdistance all we passing and temporary actors on its solid stage of confused human events.

“Here is a recollection of the summer of 1954 and I am sunbathing on Fraserburgh beach aged nine.

“There is a sudden summer shower of rain. Luckily, it almost immediately passes.

“I wander off on my own, through the harbour with its ‘painted’ herring boats, and off towards the point, up along the rugged cliffs.

“I look out over the vast scale of distantly blue horizons.

“I’ve never seen the sea so deep blue. I’ve never seen the sun so smilingly and cheaply easy with its free intensity.

“I’ve never felt such a tingle of joy on my skin.

“If you have all this, I thought, who would have need of a God?”