Thousands of pages of testimony have been submitted, and more than a dozen witnesses have been grilled by MSPs since the summer.

Now, as the committee leading the ongoing Holyrood inquiry into the Scottish Government’s botched investigation into allegations against Alex Salmond takes a break until the New Year, we look back at some of the most significant evidence to emerge so far from the hearings:

A lot happened in November 2017

Multiple key events in the inquiry date back to a few weeks in 2017, when the viral #MeToo tidal wave of sexual harassment allegations, which started with claims against movie producer Harvey Weinstein, made it from Hollywood to Holyrood.

At the end of October lawyer Aamer Anwar went public with claims that women had been sexually harassed at the Scottish Parliament, and the following day First Minister Nicola Sturgeon wrote to Presiding Officer Ken Macintosh, asking what additional steps might be taken to protect staff.

On the next day, October 31, the Cabinet discussed the issue, hearing that the first minister had asked the permanent secretary to undertake a review of government policies and processes to ensure that they were fit for purpose.

Over the next month or so, Early Years Minister Mark McDonald resigned over harassment allegations, Ms Sturgeon and government officials were told Sky News was working on a story about Mr Salmond’s conduct at Edinburgh Airport in 2009, a controversial new harassment policy was drafted to cover both current and former ministers, and two women came forward who would later make complaints against Mr Salmond.

Concerns about the conduct of ministers were raised privately many times

Dave Penman, general secretary of the FDA civil servants’ union, told the inquiry that staff were concerned about bullying behaviour in the former first minister’s office.

He also said 30 officials had raised concerns about Scottish ministers’ behaviour over the last decade, a “remarkable” number when compared with the civil service elsewhere in the UK.

Mr Penman revealed concerns about inappropriate behaviour remained today, three years after new anti-harassment procedure was introduced in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

The UK Cabinet Office did not support the harassment policy used against Alex Salmond

The creation of the government harassment policy that dealt with complaints against Alex Salmond has been an important focus of the committee.

Evidence submitted to the inquiry shows that by November 7 2017 a first draft of a new policy that could be applied to former ministers was produced by James Hynd, head of the cabinet, parliament and governance division at the Scottish Government.

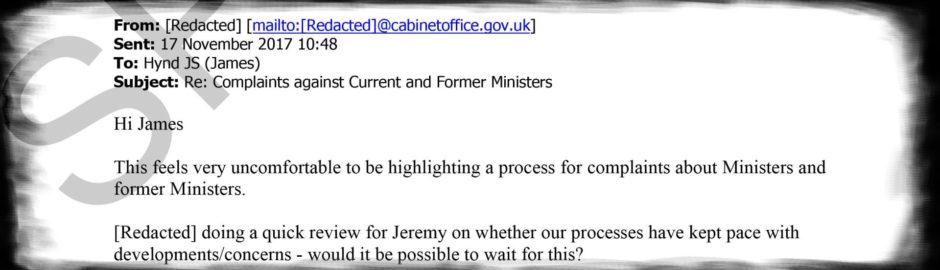

Nine days later, Mr Hynd sent a copy of the proposed policy to the UK Government’s Cabinet Office seeking “thoughts/advice”.

A Cabinet Office official responded, saying: “This feels very uncomfortable to be highlighting a process for complaints about ministers and former ministers.”

The Whitehall contact went on to ask if the policy could wait until they had conducted their own review, and the unnamed individual also questioned whether the policy for ministers was “more than you have in place” for civil servants.

Mr Hynd forwarded the Cabinet Office response to a Holyrood private secretary, who replied: “Oh dear, I did wonder if that would be their reaction.

“Not sure how long their review will take but FM and Perm Sec keen to resolve quickly and to discuss on Tuesday.

“I suspect we don’t have a policy on former civil servants.”

Nicola Sturgeon has not spoken to Alex Salmond since 2018

They are the two most significant figures in recent Scottish political history but in her written evidence to the inquiry Ms Sturgeon revealed extent of the “breakdown” of her relationship with Mr Salmond.

She said one of the reasons she decided to meet him on April 2 2018 was the “personal aspect” of their relationship.

“Mr Salmond has been closer to me than probably any other person outside my family for the past 30 years, and I was being told he was very upset and wanted to see me personally,” Ms Sturgeon said.

She later added: “My view throughout was that complaints must be properly and fairly considered, no matter who the subject of them might be, or how politically inconvenient the investigations may be.

“And that remains my view, even though the circumstances and consequences of this particular investigation have caused me – and others, in many cases to an even greater extent – a great deal of personal anguish, and resulted in the breakdown of a relationship that had been very important to me, politically and personally, for most of my life.”

Ms Sturgeon revealed she last spoke to her former mentor by telephone on July 18 2018 when she told him she wanted to “draw a line under our contact”.

He was in touch twice shortly afterwards, but she did not respond.

Nicola Sturgeon’s evidence is at odds with the testimony given by her husband

One of the most significant moments in the inquiry to date was when the committee heard from Peter Murrell, the SNP’s long-serving chief executive, and husband to Ms Sturgeon.

In particular, several MSPs focused on his explanation of two key meetings in 2018 held in his marital home, between Mr Salmond and Ms Sturgeon.

The meetings were already viewed as key events because Ms Sturgeon has said that it was at the first summit that Mr Salmond told her about the government’s investigation into him for the first time.

In written evidence to the committee, the first minister said she had agreed to meet her predecessor because she believed he was about to resign from the SNP, and “as party leader, I considered it important that I knew if this was, in fact, the case in order that I could prepare the party to deal with what would have been a significant issue”.

However, Mr Murrell suggested that his wife did not meet Mr Salmond in her capacity as SNP leader, but as first minister of Scotland.

While denying that he was told about the nature of the discussion, he said the “issue raised at the time was a Scottish Government matter”, and therefore he did not need to know.

Under the ministerial code, if Ms Sturgeon held the meetings in her capacity as first minister, as Mr Murrell suggested, then the details of the discussion should have been officially recorded.

Ms Sturgeon and Mr Salmond will both be asked about the meetings when they give evidence.

Alex Salmond accuser twice met Nicola Sturgeon’s aide before lodging complaint

It emerged in November that one of the two women who went on to make a complaint to the government about Mr Salmond had meetings with Ms Sturgeon’s principal private secretary, John Somers, on November 20 and 21 2017.

When they emerged, details of the meetings fuelled claims that the harassment policy being drawn up by the government at that time was designed for use against Mr Salmond.

That was because just one day later, on November 22, Mr Somers forwarded a letter from Ms Sturgeon to Scotland’s most senior civil servant, Leslie Evans, asking the permanent secretary to confirm that the new harassment policy being drawn up included consideration of complaints made against former ministers dating from when they were in office.

When he later gave evidence to the committee, Mr Somers denied informing Ms Sturgeon or anyone other than his line manager about what was discussed.

The two women who complained about Alex Salmond did not want to contact the police

Judith Mackinnon, the civil servant who led the government’s botched internal investigation into the complaints against Mr Salmond, told the committee she had been asked to “sound out” the two complainers about reporting to the police.

Murdo Fraser MSP asked her: “Would it be fair to say that the complainants were reluctant themselves to report to the police?”

Ms Mackinnon said: “You could say that. I don’t think it had been their intention, when they initially had come forward, to do that.”

Nicola Richards, director of people at the Scottish Government and Ms Mackinnon’s line manager, confirmed the women did not want their complaints about Mr Salmond to go to the police.

“I think it was very clear that it was not their wish, not their preference. It had not been, I think, where they had begun,” she said.

“I think they fully understood, and we were always clear, that it might be a judgement as an organisation that we had no choice but to refer the matter to the police, and they fully understood that.”

Ms Richards also confirmed it was Leslie Evans, the permanent secretary, who had taken the final decision to contact the police.

Angus Robertson received a complaint about Alex Salmond in 2009

The committee recently received written evidence from Mr Robertson, the former Moray MP and SNP Westminster leader, who is seen as an ally of Ms Sturgeon and a potential successor.

He denied that he had any evidence relevant to the inquiry’s remit, but then went on to confirm previous reports that he had been made aware of a concern about Mr Salmond in 2009.

Mr Robertson said he was called by an Edinburgh Airport manager about Mr Salmond’s “perceived inappropriateness” towards female staff at the airport.

“I was asked if I could informally broach the subject with Mr Salmond to make him aware of this perception.

“I raised the matter directly with Mr Salmond, who denied he had acted inappropriately in any way.”

Mr Robertson said he later considered the matter “resolved”, and that it was not reported further.

The last part was crucial, because Ms Sturgeon, Mr Murrell and others have been clear that they were not aware of any such concerns about Mr Salmond’s conduct until many years later.

They have said they were first made aware of the Edinburgh Airport incident, and Mr Salmond’s alleged behaviour, in November 2017, when Sky News contacted the SNP press office about it.

Ms Sturgeon is bound to be quizzed by the committee on whether Mr Robertson mentioned it to her earlier.

Peter Murrell suggested ‘pressurising’ police

An intriguing dimension to the inquiry has been the emergence of text messages sent by Mr Murrell after Mr Salmond had appeared in court, facing criminal charges.

During the trial, which resulted in Mr Salmond being cleared of all sexual offence charges earlier this year, the former first minister claimed the allegations against him were “deliberate fabrications for a political purpose”.

His supporters have also claimed the former first minister was a victim of a conspiracy. These suggestions were raised when Mr Murrell was quizzed about his texts by the Holyrood inquiry.

Mr Murrell sent the messages in January 2019, which was also the month when a separate complaint was made about the former SNP leader to the Metropolitan Police, which the London force later dropped.

In the messages, Mr Murrell said it was a “good time to be pressurising” police and that the “more fronts he (Mr Salmond) is having to firefight on the better for all complainers”.

When he appeared in front of the Salmond inquiry, Mr Murrell said it was “not true” that the messages were evidence of a plot against Mr Salmond.

Mr Murrell said he regretted the wording of the messages, saying they were “open to misinterpretation” and were a sign of how upset he was at the time.

He said his intention was to direct those with questions about the charges to the police or Crown Office.

Nicola Sturgeon forgot about meeting with Alex Salmond’s former chief of staff

Ms Sturgeon told the Scottish Parliament that Mr Salmond first told her about the Scottish Government’s internal investigation into harassment claims against him when they met at her Glasgow home on April 2 2018.

She also told MSPs she met him again on June 7 at the SNP conference in Aberdeen and another time at her home on July 14 2018.

They also spoke by telephone on April 23 and July 18 2018. Ms Sturgeon told Holyrood she did not inform civil servants of her April meeting with the former first minister until two months after the event.

Ms Sturgeon has always insisted that she acted appropriately, but her opponents have suggested she breached the ministerial code, which states meetings on official government business have to be set up through government office and detailed records made of those contacts.

However, during Mr Salmond’s trial, it emerged there was a meeting before April 2 with Mr Salmond’s former chief of staff, Geoff Aberdein, which Ms Sturgeon did not mention at Holyrood.

In her submission to the Salmond inquiry, Ms Sturgeon said the meeting with Mr Aberdein had slipped her mind until she was reminded about it early last year, adding she thought it might have covered allegations of a “sexual nature”.

The SNP’s disciplinary process was not followed in the case of Mark McDonald

The case of Mr McDonald, the Aberdeen Donside MSP, has not been considered as part of the inquiry to date, but the evidence has raised fresh questions about the handling of allegations against him.

It has even been suggested that Mr McDonald was forced to resign from his post as early years minister in November 2017 in order to justify the need for a new harassment policy that could be used against Mr Salmond.

The committee has heard that Nicola Sturgeon first became aware that Sky News was investigating a story about Mr Salmond’s conduct on the same night that Mr McDonald was told to quit.

Peter Murrell’s description to the committee of the SNP’s complaint-handling process also did not match accounts previously given by Mr McDonald of the way allegations against him were dealt with.

Scottish Government has been slow to hand over information to the inquiry

A strong theme of the Salmond inquiry has been the committee’s anger over the Scottish Government’s attitude towards handing over documents – in particular the legal advice it received when it was being challenged by Mr Salmond in the civil courts.

Mr Salmond defeated the Scottish Government in a Judicial Review, which found that the Scottish Government’s internal investigation into the claims against Mr Salmond was tainted with apparent bias.

The judgement led to more than £500,000 paid out to cover Mr Salmond’s legal costs and led to Holyrood’s Salmond inquiry.

The Scottish Government has argued the legal advice is covered by privilege, arguing that it is an important principle that such information should remain confidential.

However, a majority of MSPs have now voted twice for the advice to be handed over, inflicting two embarrassing defeats to the government on the issue.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney has said the Scottish Government will consider the view expressed by Holyrood.